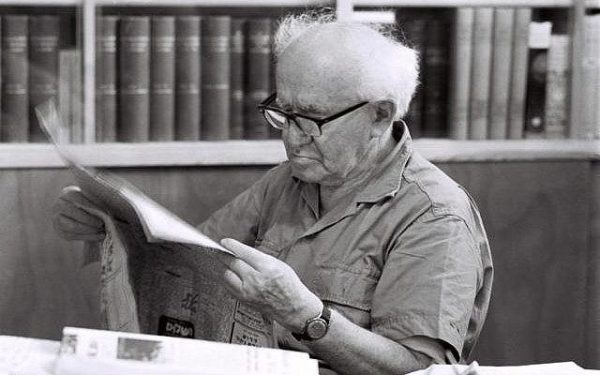

Benjamin Netanyahu marked a historic milestone on July 20 amid speculation whether he will still be Israel’s prime minister after the September 17 general election. Having held office for 4,876 days, or slightly more than 13 years, he surpassed David Ben-Gurion — Israel’s first and probably greatest leader — as its longest-serving prime minister.

Netanyahu, a populist who heads the right-wing Likud Party, won the last election in April. He then spent more than 40 days in vain attempting to cobble together a coalition government. He fell short of the mark because his former defence minister, Avigdor Liberman, would not join his government and give him a majority of 61 Knesset seats. Liberman balked because he opposed a military conscription bill that Netanyahu sought to modify, but that he wanted to preserve in its current form.

Having been stymied by Liberman, Netanyahu became the first sitting Israeli prime minister to fail to form a government after winning an election.

Netanyahu could have thrown in the towel, thereby allowing a rival, Benny Gantz of the centrist Blue and White Party, to try his hand at forming a government. But Netanyahu, who is facing criminal indictments on charges of bribery, fraud and breach of trust filed against him by Attorney-General Avichai Mandelblit, categorically rejected that option because he feared imprisonment if someone else was at the helm of the government. Netanyahu was acutely aware that one of his predecessors, Ehud Olmert, went to jail in 2016 after being found guilty of corruption.

Netanyahu’s calculations were in keeping with his penchant for political self-preservation.

Despite these concerns, Netanyahu was doubtless in an upbeat mood on July 20. Having been elected prime minister four times, he thereby matched Ben-Gurion’s heretofore unassailable record of longevity. Netanyahu also holds another record. He’s the only Israeli prime minister to have been reelected three consecutive times — 2009, 2013 and 2015.

Despite his successes at the polls, Netanyahu is not universally popular. A polarizing figure, he is loved by his supporters but hated by his opponents.

Now 69 and turning 70 in October, Netanyahu was the first prime minister to be born after the establishment of Israel. First elected in 1996, he was the youngest person to hold that office. Having lived and studied in the United States for many years before returning permanently to Israel, he is the first Israeli prime minister who can speak fluent, idiomatic English.

A management consultant by profession and an architect by training, Netanyahu served in the Israeli armed forces during the Six Day War, War of Attrition and Yom Kippur War. He comes from a Polish Revisionist Zionist family that was ideologically at odds with the Labor Zionist movement, which formed every Israeli government from 1949 until 1977, the year Menachem Begin shattered its monopoly and was chosen as prime minister in a political earthquake.

Like his father, a historian, Netanyahu is a hardliner. He opposed territorial compromise and Palestinian statehood, scoffed at the idea that a peace agreement with the Arabs was possible, and believed that Israel’s natural borders should stretch from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea. After the Six Day War, he rejected the notion that Israel should exchange the new territories — the Sinai Peninsula, the Gaza Strip, the West Bank and the Golan Heights — for peace with its Arab neighbors.

In short, Netanyahu favored the status quo.

Netanyahu was inducted into politics by his mentor, Moshe Arens, who was both minister of defence and foreign affairs. Due to Arens’ influence, he was appointed ambassador to the United Nations in 1984. During the 1991 Gulf War, when he was deputy foreign minister, he was Israel’s official spokesman. In these positions, Netanyahu proved he was a first-class orator.

Netanyahu, having been elected to the Knesset, gradually took control of the Likud after the premierships of Menachem Begin and Yitzhak Shamir, pushing aside heirs apparent like Dan Meridor and Roni Milo. Like Begin, Netanyahu portrayed himself as an anti-Establishment figure who would fight the entrenched elites.

Prior to Yitzhak Rabin’s assassination in 1995, Netanyahu railed against the 1993 Oslo accords and appeared at rallies where Rabin was demonized and likened to a Nazi SS officer.

Surprisingly, Netanyahu defeated frontrunner Shimon Peres, the prime minister, in the 1996 election. He beat him by a very slim margin following a spate of Palestinian suicide bombings that hardened Israeli public opinion. Netanyahu’s victory, hailed by the nationalist-religious camp, came as a bitter blow to liberal Israelis who supported the land-for-peace formula and assumed that Oslo could not be reversed.

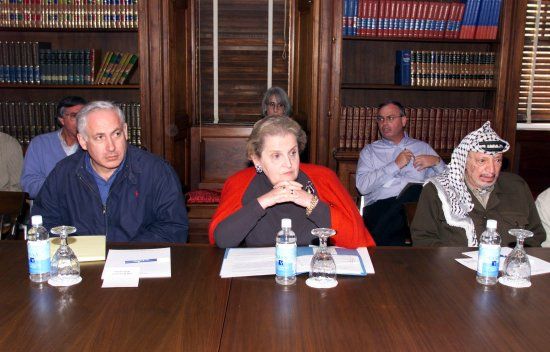

Netanyahu ran his campaign on an anti-Oslo platform, but due to U.S. pressure, he was forced to grudgingly accommodate himself to that agreement. Eventually, he was compelled to meet his arch foe, PLO chairman and Palestinian Authority President Yasser Arafat.

Under prodding by the Bill Clinton administration, Netanyahu agreed in 1997 to relinquish all of Hebron to the Palestinian Authority except for a small enclave populated by Jewish settlers whose ancestors had been driven out of that West Bank town during the lethal 1929 riots. But in a demonstrable signal to his base, he expanded Jewish settlements in the West Bank and announced that construction of Har Homa, a new Jewish neighborhood in East Jerusalem, would soon commence.

All in all, Netanyahu’s policies had a chilling effect on the Oslo agreement.

In 1997, Netanyahu ordered the assassination of Khaled Mashal, a top-ranking Hamas official based in Amman. Mossad agents, having sprayed him with a poisonous substance, were caught, leading to a crisis in Israel’s relations with Jordan. Forced to accede to King Hussein’s demands, Netanyahu sent an antidote to treat Mashal and released Sheikh Ahmed Yassin, Hamas’ spiritual leader, from prison.

Netanyahu went down to defeat in the 1999 election, trounced by the Labor Party’s Ehud Barak, an ex-chief of staff of the armed forces and Netanyahu’s former army commander. Licking his wounds, Netanyahu left politics and went into business. Several years later, he joined Ariel Sharon’s government, first as foreign minister and then as finance minister.

Subsequently, Netanyahu assumed the Likud leadership.

Tzipi Livni, the leader of the centrist Kadima Party, edged out Netanyahu in the 2009 election. Poised to become Israel’s second female prime minister after Golda Meir, she was unable to form a government, catapulting Netanyahu back to his old job.

At U.S. President Barack Obama’s request, Netanyahu endorsed a two-state solution. In a speech at Bar-Ilan University shortly after his reelection, he came out in favor of a demilitarized Palestinian state on condition that the Palestinians recognize Israel as a Jewish state. Netanyahu, however, only paid lip service to a two-state solution. Later, again under pressure from the Obama administration, he imposed a partial building freeze on the construction of new settlements in the West Bank. In general, Netanyahu’s relationship with Obama was tense.

In 2012, Netanyahu waged his first war against Hamas in the Gaza Strip. The truce, such as it was, crumbled in 2014 as Israel and Hamas fought an even longer and more deadly war. Since then, Israel’s border with Gaza has been volatile, with skirmishes breaking out regularly and temporary ceasefires ending them.

At the behest of the United States, Netanyahu resumed peace negotiations with the Palestinian Authority in 2013. His interlocutor was Mahmoud Abbas, the former prime minister and Arafat’s successor. After about a year of fitful talks, the process collapsed in a welter of mutual recriminations.

Toward the close of the 2015 election campaign, Netanyahu warned his supporters he might lose because Israeli Arab voters were coming out “in droves” to cast their ballots for left-of-center parties. Netanyahu’s demonization of Israeli Arabs was offset by his subsequent plan to pump more than $1 billion into their community.

For the past few years, Netanyahu has focused on Iran, Israel’s arch enemy, to the exclusion of the Palestinians. In 2012, he came close to launching a massive air raid against Iran’s nuclear sites. Three years later, he criticized the emerging Iran nuclear agreement, which would be signed by the major powers in 2015. He denounced it as a “historic mistake” in a speech to the U.S. Congress. Netanyahu has consistently said he will not tolerate a nuclear-armed Iran.

Since 2016, Netanyahu has stepped up Israel’s covert air war against Hezbollah weapons convoys bound from Syria to Lebanon. The Israeli Air Force also has bombed Iranian military bases in Syria, which has been torn by a civil war for the past eight years.

Israel’s on-again, off-again military confrontation with Iran, which Russia has attempted to defuse, may yet explode into a full-fledged war.

Netanyahu’s focus on containing Iran has sidelined Israel’s conflict with the Palestinians, in accordance with his strategy. In the meantime, Netanyahu has courted conservative Arab states such as Qatar, Oman, United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia, all of which fear Iranian ambitions in the Middle East. Elsewhere, Netanyahu has curried favor with right-wing populist governments.

Since Donald Trump’s accession to the U.S. presidency in 2016, Netanyahu has gradually distanced himself from his endorsement of a two-state solution, and now favors nothing more than local autonomy for the Palestinians, a position they totally reject. During the last Israeli election campaign, Netanyahu spoke of annexing Jewish settlements in the West Bank.

In Trump, Netanyahu has found a kindred soul. Trump recognized Jerusalem as Israel’s capital, moved the U.S. embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, and recognized Israeli sovereignty over the Golan Heights. But during this period, Israel has increasingly been identified with the Trump administration and become a partisan issue in U.S. politics.

Looking back at his checkered record of governance, Netanyahu has managed Israel’s internal affairs quite competently, presided over an era of prosperity despite the existence of a substantial underclass, and kept terrorism to a minimum.

The charges of corruption levelled against him have tarnished him immeasurably. And his repudiation of the two-state solution, plus his advocacy of the West Bank settlement project, may yet threaten Israel’s integrity as a democratic Jewish state.

That may be his ultimate legacy.