He witnessed degradation, starvation and death in the Warsaw ghetto.

He clandestinely visited a Nazi transit camp.

He warned Western democracies that Jews in Poland were being systematically murdered by the Nazis.

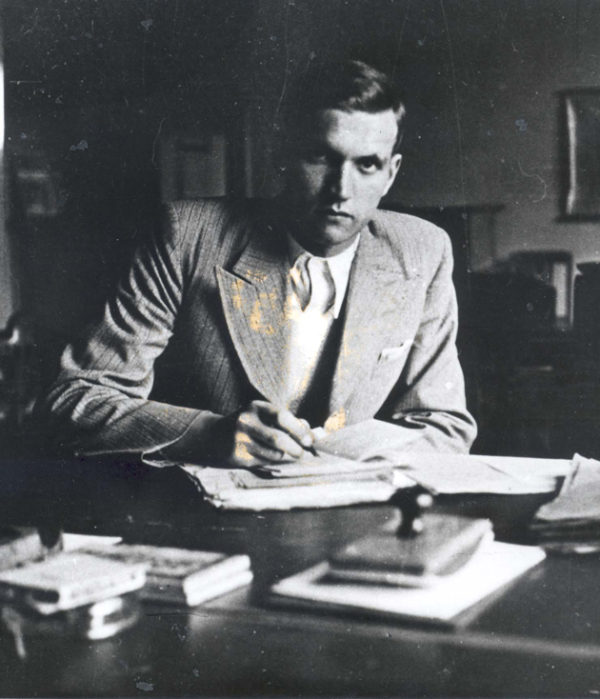

He was Jan Karski, the courageous courier from the Polish government-in-exile.

The newest documentary about this heroic Polish figure, Karski & The Lords Of Humanity, was premiered in Poland last year and is coming to Toronto next week thanks to the Konstanty Reynert Chair of Polish Studies at the University of Toronto and the Polish-Jewish Heritage Foundation.

The film, directed by Slawomir Grunberg, will be screened on Monday, April 25 at 7 p.m. at the University of Toronto’s Innis College. Admission is free.

Karski, who died 16 years ago at the age of 86, is portrayed as an eminently decent man who fought for Poland and tried to save the remnants of its Jewish minority. Being a modest and reticent person, he rarely spoke about his dangerous mission after the Holocaust, but when he chose to speak, he was passionate and articulate.

Grunberg’s biopic, which is written by Katka Reszke, takes a viewer from his birthplace in Lodz to his adopted homeland in the United States. It’s based on conversations French filmmaker Claude Lanzmann conducted with Karski in the mid-1980s, on interviews with Jewish leaders and Karski’s biographer, and on archival newsreels. Animated footage gives it an extra edge.

Karski studied law and diplomacy, hoping to join the Polish foreign service. His career hopes were dashed when Germany and the Soviet Union successively occupied Poland in September 1939. Instead of becoming a diplomat, he became an officer in the Polish army. Falling into the hands of the Soviets in eastern Poland, he was fortunate to escape. Thousands of his fellow officers would soon be killed by the Soviet Union at Katyn.

After joining the Polish underground, he was sent to France, where the Polish government-in-exile asked him to prepare a report about the plight of European Jews. Captured by the Gestapo in Slovakia, he was tortured. With the help of local partisans, he escaped.

In the summer of 1942, with the Holocaust under way, Karski met two Jewish representatives in Warsaw who told him what was happening to Jews in Nazi-occupied Poland. Karski quickly realized that Germany’s genocidal plans were unprecedented in the annals of history.

At the suggestion of the Bund, he secretly visited the Warsaw ghetto in September and October of 1942. By that juncture, the majority of its Jewish inhabitants had been deported to Nazi extermination camps. Karski’s objective was to observe and remember. Since he had a photographic memory, he had no trouble recalling the smallest details.

His guide urged him to return for a second look and he did so. The stench was overwhelming, he notes, and the tension and nervousness in the air were palpable. As Karski remembers his trip into hell, he breaks into tears. “Nobody wrote about this kind of reality,” he says bitterly, hardly believing what he had seen.

This segment of the film is filled with horrible images of ragged people wandering the streets aimlessly and corpses lying askew on sidewalks.

After absorbing the horrors of the ghetto, he was smuggled into a Nazi transit camp from which Jewish inmates were shipped to death camps. Upon leaving, he vomited blood. Karski had been deeply moved.

Having written a comprehensive report about Germany’s maltreatment of Jews, Karski went to London to brief Polish, British, French and Jewish officials about his unsettling findings.

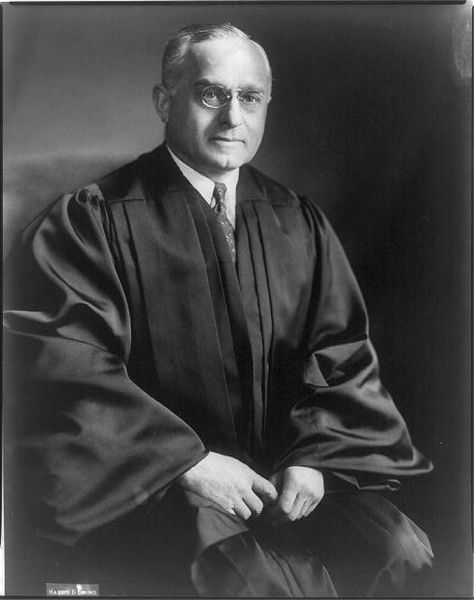

In 1943, in Washington, he told Felix Frankfurter, a Jewish justice on the U.S. Supreme Court, about Nazi atrocities unfolding in Poland. Incredibly enough, Frankfurter was skeptical. He expressed admiration for Karski’s work, but also disbelief about Nazi intentions.

During his next encounter, he met President Franklin Roosevelt. Karski warned him that millions of Jews would perish unless the Allies intervened. Roosevelt voiced sympathy and asked questions, but seemed more interested in Poland’s agriculture sector.

As Karski talks about these frustrating meetings, he stands up in anger, paces, gesticulates in a gesture of futility and pokes fun at Roosevelt.

He left Washington with the impression he had failed, but the opposite was true. Karski’s damning report was, in fact, a turning point in the Allies’ response to the Holocaust. In 1944, the United States established the War Refugee Board, which played a role in the rescue of Jews.

Karski was a brave and honorable man who exposed Nazi crimes, and Grunberg’s impassioned film conveys the magnitude of his humanitarian achievement.