The new ceasefire in southwestern Syria, brokered recently by the United States, Russia and Jordan, has led to the first public dispute between Israel and the Trump administration.

The truce, the culmination of months of negotiations in which Israel was involved, was announced on July 7 following the first meeting between U.S. President Donald Trump and Russian President Vladimir Putin, which took place in Hamburg, Germany. It creates buffer zones around the towns of Quneitra, Sweida and Daraa, all close to the Jordanian and Israeli borders. They will be patrolled by Russia in coordination with the United States and Jordan.

U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson presented the truce as an example of how the United States and Russia can “work together in Syria” to create yet more de-escalation zones and thus end the six-year-old civil war in that deeply fractured nation.

The United States and Russia have both assured Israel that its security needs have not been compromised by the agreement. “I can guarantee that the American side and we did the best we can to make sure that Israel’s security interests are full taken into consideration,” Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov said on July 17.

On the same day, Trump’s press secretary said that Israel’s concerns had been addressed. As he put it, “There’s a shared interest that we have with Israel, making sure that Iran does not gain a foothold, military base-wise, in southern Syria.”

To the Israeli government, however, news of the limited Syrian truce was treated as setback.

Speaking in Paris after talks with French President Emmanuel Macron, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu expressed disapproval of it, claiming it will perpetuate Iran’s presence in Syria and thereby weaken Israel’s grip on the Golan Heights, a strategically important plateau overlooking the Sea of Galilee.

Iran, Israel’s arch enemy since the 1979 Islamic revolution, has been Syria’s closest ally for almost 40 years now. Since the eruption of the Syrian civil war in 2011, Iran — the preeminent Shiite power in the Middle East — and its surrogate, the Lebanese Shiite militia Hezbollah, have fought alongside Syria in a bid to defeat Sunni Syrian rebels opposed to President Bashar al-Assad’s Baathist regime.

Assad and his inner circle are disposed toward Iran because they’re members of the minority Alawite sect, a branch of Shiaa Islam.

In recent years, Iran has attempted to set up a base on the Syrian-held side of the Golan. Israel has pushed back. In January 2015, an Israeli helicopter gunship killed Ali Allahdadi, an Iranian general touring the region, as well as Jihad Mughniyeh, the son of the Hezbollah military commander assassinated in Damascus in 2008.

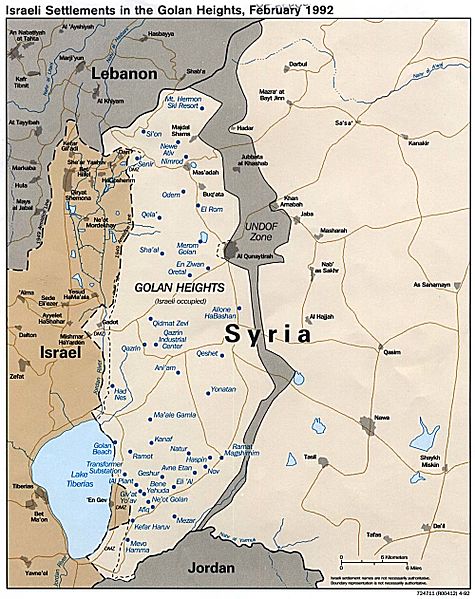

Israel captured two-thirds of the Golan from Syria during the last phase of the 1967 Six Day War and annexed it in 1981. Syria tried to recapture the Golan during the 1973 Yom Kippur War. A long-term agreement, hammered out by U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger in 1974, brought tranquility to the Golan, which became Israel’s quietest front.

During the 1990s, Israel and Syria conducted on-again, off-again talks on the future of the Golan, but they failed to resolve all their differences. Earlier this year, Netanyahu declared that Israel will not relinquish the Golan, which is populated by Syrian Druze citizens and Jewish settlers.

Shortly after Netanyahu voiced misgivings about the truce in southern Syria, his office released a statement outlining Israel’s “red lines” in Syria.

- Iran and Hezbollah must be kept sufficiently far away from Israel’s side of the Golan.

- Iran cannot be permitted to establish a military beachhead in Syria.

- Hezbollah cannot be allowed to acquire game-changing state-of-the art weapons.

Compared to the West Bank, the sparsely-populated Golan has presented Israel with very few problems. But of late, the situation there has changed, much to Israel’s disadvantage.

A variety of extremist groups linked with the jihadist organization, Islamic State, have seized approximately 20 percent of the Syrian portion of the Golan. Sunni rebels, including Al Qaeda allies, hold an additional 65 percent. The Russian-backed Syrian army, Shiite militias aligned with Iran and Druze fighters are in control of about 15 percent.

This is not the only problem Iran poses to Israel.

Like its Sunni Arab neighbors, Israel is concerned by Iran’s regional ambitions.

In their view, Tehran has a much broader agenda than creating a sphere of influence on the Golan. Iran, they believe, wants to create a land corridor from Iranian territory to Syria and Lebanon. This land bridge could enhance Iran’s regional clout and allow it to send military supplies directly to surrogates like Hezbollah and various Shiite militias. Israeli aircraft have bombed suspected Hezbollah arms convoys heading to Lebanon from Syria, but other convoys have made it through unscathed.

The concern that Israel shares with Arab Sunni states is that this Shiite corridor could easily disrupt the balance of power in the region at their expense and, for the first time, bring Iran to the shores of the Mediterranean Sea.

A top-ranking Iranian official has openly acknowledged Iran’s objectives in the Middle East. “Today, the resistance highway starts in Tehran and passes through Mosul and Beirut to the Mediterranean,” said Ali Akbar Velayati, a senior advisor to Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

Another flashpoint could be the underground factories Iran is building or has already built in Lebanon to produce precision-guided missiles for Hezbollah. The director of Israeli military intelligence, General Herzl Halevy, has suggested that Israel might resort to preemptive air strikes to destroy these facilities.

Certainly, Iran has the technical knowledge to bring this task to completion. Last month, in retaliation for terrorist attacks in Tehran, Iran launched ballistic missiles at Islamic State bases in Syria.

Yaakov Amidror, Netanyahu’s former national security advisor, warns that Israel will not tolerate Iran’s plans. “We will not let the Iranians and Hezbollah be the forces which win from the long and brutal war in Syria,” he said.

If Israel’s interests are directly threatened, he added, Israel may well be forced to intervene directly in Syria’s civil war.

Under Operation Good Neighbor, Israel has sent tons of humanitarian supplies — food, medicine and medical equipment — to politically mainstream rebels in Syria and has treated wounded Syrians in Israeli hospitals.

Since the start of the Syrian civil war, Israel has usually responded to errant artillery and tank fire from Syria in tit-for-tat fashion. In some cases, Israeli aircraft have bombed Syrian military positions. But if Iran gains a foothold on the Golan, Israel would be forced to play a far more aggressive role in Syria.