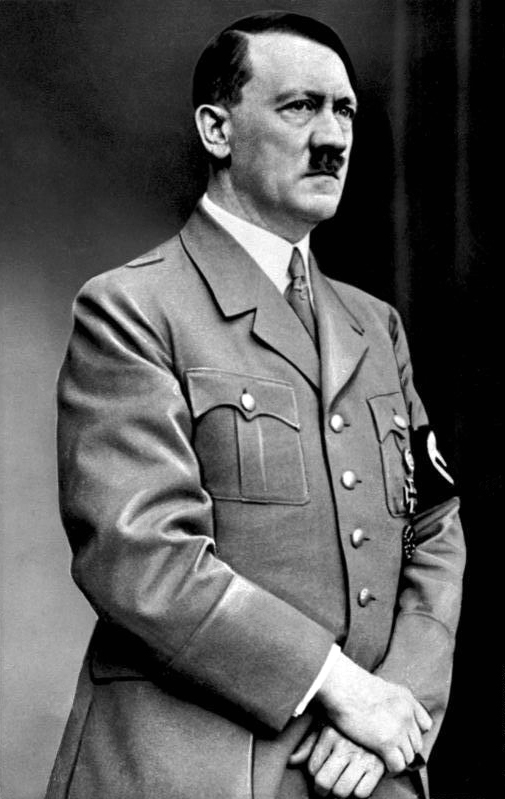

Adolf Hitler is the epitome of evil, the arch aggressor who ignited World War II and the malevolent force who conceived and implemented the Holocaust.

For much of the period after 1945, Hitler’s Nazi regime was viewed through this prism, as the Federal Republic of Germany accepted full responsibility for Hitler’s unprecedented crimes against Jews and other Europeans, prosecuted a number of Nazi war criminals and doled out reparation payments to the Jewish victims of the Holocaust.

Germany’s atonement for its Nazi past was reinforced by a panoply of gestures in the form of memorials, museums and ceremonial speeches by major politicians.

German Chancellor Willy Brandt’s decision to kneel down in front of the Warsaw Ghetto Heroes Monument while on a state visit to Poland in 1970 offered dramatic proof that a new Germany had arisen.

But even as a succession of German governments rehabilitated Germany’s image by making moral and material amends, some Germans tried to “normalize” the Nazi interregnum by focusing on the wartime suffering their fellow countrymen had endured rather than on the pain Germany had inflicted.

These revisionist views were resisted by the younger generation in a vigorous backlash starting in the late 1960s.

During the 1980s, however, German conservatives, led by Chancellor Helmut Kohl, revisited the theme of normalizing the Nazi epoch so that Germany could finally establish a positive sense of national identity. Kohl’s argument was adopted by, among others, the writer Martin Walzer and the politician Jurgen Mollemann, both of who attempted to relativize Nazi crimes.

Since the turn of the millennium, this trend has gathered fresh momentum, with Hitler having been transformed into “a more ambiguous figure,” claims Gavriel D. Rosenfeld in Hi Hitler! How the Nazi Past is Being Normalized in Contemporary Culture (Cambridge University Press).

“Originally mocked, subsequently feared, posthumously vilified, Hitler today is becoming normalized,” he writes in this fascinating and perceptive book.

Normalization has manifested itself in diverse areas of contemporary intellectual and cultural life, he argues. “It has appeared in sophisticated works of academic scholarship and journalism, in popular novels and short stories, in works of film and television, and, most prominently, on innumerable Internet websites.”

Its goal, he adds, is to overturn “the perceived exceptionality of the Nazi era” so that Germans can reclaim a sense of national pride and establish a normal identity.

This revisionist campaign draws attention to the Allied air raids on German cities, the mass expulsions of ethnic Germans from their homes in such countries as Poland and the rape of hundreds of thousand German women by Red Army soldiers.

This campaign marks an important shift in German memory of World War II, says Rosenfeld, a professor of history at Fairfield University in the United States. “By focusing on Germans as victims, they inevitably shifted attention towards the Allies as perpetrators. In the process, they blurred the line between Allied and Axis crimes and implicitly relativized German guilt for the Nazi era.”

In response, Jewish historians such as Saul Friedlander and Deborah Lipstadt published a series of studies that underscored the singularity of the Holocaust.

Films have been at the center of this debate, too.

Leni Riefenstahl, in documentaries like Victory of Faith (1933), Triumph of the Will (1935) and Olympia (1938), transformed Hitler into a “figure of omnipotence.” Charlie Chaplin, in The Great Dictator (1940), mocked Hitler.

Comic portrayals of Hitler in movies became taboo after 1945. Since about 2000, though, a plethora of films, from Max to Inglorious Basterds, have attempted to humanize Hitler by adopting a less judgmental tone and depicting him as a flawed human being.

Such movies, Rosenfeld warns, may well impede a real understanding of Hitler: “The more that films insist on humanizing Hitler — through whatever aesthetic means — the more they risk trivializing him.”

Users of the Internet researching the Third Reich should be careful, he notes. With a few clicks, a user reaches neo-Nazi sites that glorify Hitler. Still more clicks lead to Uncyclopedia, a site which offers mock entries about Hitler and Nazism, and to Hipster Hitler, which features comic strips of Hitler wearing Nazi-themed T-shirts. Bizarrely enough, there is even a site called Cats That Look Like Hitler.

Not surprisingly, Hitler’s name has been invoked for crass commercial ends. Advertisers around the world have employed his image to sell wine in Italy, condoms in Holland, televisions in India, eggs in South Africa, tea in Turkey and pizza in South Africa.

“In short, wherever one looks, Hitler and the Nazis are everywhere,” writes Rosenfeld. “Once upon a time, Hitler and the Nazis were viewed as admonishing symbols of extremity. Today, their ubiquity has lent them an aura of normality.”

This transformation of the Nazi legacy, he notes, stems from a powerful wave of normalization that has swept across the universe in the past 16 years.

The global tide of normalization is driven by several factors, he says.

As the older generation dies off, the moralistic modes of representing Nazi Germany and Hitler have progressively disappeared. “As a result, younger people born in the decades since 1945 have increasingly shaped present-day cultural memory. Representatives of this generation have played a leading role, for example, in historiographical forms of normalization. Many of the scholars who have challenged the idea of the Holocaust’s uniqueness … were born in the 1960s or after.”

It’s a disturbing yet unavoidable development in a nation still trying to come to terms with the Nazi era.