On July 18, two days before the deadline for reaching a permanent agreement on the future of Iran’s controversial nuclear program was due to expire, six major powers and Iran agreed to extend the talks by four months to Nov. 24, matching the day an interim accord was signed in Geneva in 2013.

In commenting on the extension, U.S. President Barack Obama said, “It’s clear that we’ve made real progress in several areas and that we have a credible way forward, but … there are still significant gaps between the international community and Iran, and we have more work to do.”

A few months ago, the mood was far more upbeat.

In March, Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif declared that the two sides were on track to sign a comprehensive pact by the July 20 deadline. In February, U.S. Undersecretary of State Wendy Sherman, the lead American representative at the negotiations, said that the United States was committed to signing a final deal by that date.

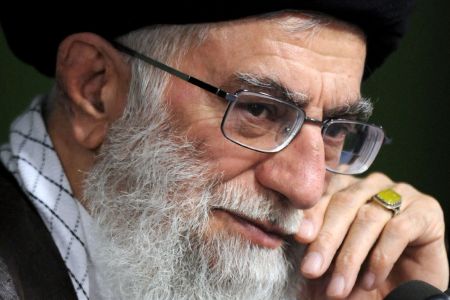

Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, was under no such illusions. Last winter, in a glum appraisal of the talks, he observed, “I am not optimistic. They will lead nowhere, but I am not against them.”

As Sherman has noted, the issues under discussion are “very complex,” and may yet be impossible to resolve. At the core of the discussions is the issue of uranium enrichment, a vital step in the process toward building a nuclear device.

While the United States and its partners — Britain, France, Germany, Russia and China — are prepared to tolerate a modest Iranian enrichment program suitable for peaceful purposes, they oppose one that would enable Iran to build an atomic weapon quickly and without detection. This is known as “breakout capability.”

They are also demanding the dismantling of most of Iran’s centrifuges, the machines that enrich uranium, and a regimen of intensive inspections by the International Atomic Energy Agency.

Ali Akbar Salehi, the head of Iran’s nuclear program, has said that Iran requires up to 100,000 centrifuges, five times as many as it has today. More recently, Ali Khamenei said that Iran will eventually need 190,000 centrifuges. By all accounts, the United States may be ready to accept between 2,000 and 4,000 centrifuges.

Several days before the nuclear negotiations were extended, Zarif told The New York Times that Iran was ready to accept temporary limitations on its nuclear program in exchange for long-term freedom of action.

In other words, Iran would be prepared to freeze its capacity to produce nuclear fuel at current levels on condition that it would be treated like any other member of the nuclear club in the years ahead.

Israel, the country that would be most adversely affected by an Iranian atomic arsenal, has called for the closure of its nuclear program. Concerned that a future agreement would enable Iran to become a nuclear state within a matter of months, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu is demanding that Iran be stripped of its capacity to manufacture a nuclear bomb.

To no one’s surprise, Israel’s demand has been completely rejected by Iran. As Zarif has said. “I can tell you that Iran’s nuclear program will remain intact. We will not close any program.”

According to the United States, Iran already has the means to build a nuclear bomb. As James Clapper, the director of National Intelligence, said in January, “Tehran has made technical progress in a number of areas — including uranium enrichment, nuclear reactors and ballistic missiles. These advancements strengthen our assessment that Iran has the scientific, technical and industrial capacity to eventually produce nuclear weapons.”

Iranian President Hassan Rouhani says that Iran, out of principle, has decided not to manufacture nuclear weapons, echoing a religious decree issued by Khamenei banning their production and use.

Few observers take these claims at face value.

Iran contends that its nuclear program is designed to produce electricity, since its vast oil and gas resources are finite. But the consensus is that Iran’s nuclear program has been militarized. Certainly, the major powers, as well as Israel and many Arab countries, share that belief.

Under last year’s interim accord, which took seven weeks to flesh out, Iran agreed to stop enriching uranium to 20 percent and neutralize its stockpile of that grade so it could not be used for military purposes. Iran, however, was permitted to enrich uranium to a level of 3.5 percent. Uranium must be refined to 90 percent purity to be fissile.

Iran also agreed not to install new centrifuges, start up any centrifuges that were not already working, or construct new enrichment facilities.

In return, the United States and the European Union lifted economic sanctions on a wide variety of products and released $4.2 billion of Iranian oil revenue frozen in overseas banks.

The interim accord, panned by Netanyahu, was a step in the right direction, giving peace a chance. Absent negotiations, Iran would have continued to develop its nuclear infrastructure, which has been sabotaged but not disabled by the United States and Israel, and the road to war between Israel and Iran would have been opened.

The question now is whether a comprehensive agreement is even attainable. Hardliners in Iran are resisting substantive concessions, while hardliners in Israel and the United States are wary of Iran’s intentions and may yet renew calls for a preemptive strike on Iran’s nuclear sites, foolhardy and dangerous as that would be.

Iran, if attacked, has promised to retaliate, a prospect that would touch off a regional war. Nearly two months ago, the deputy chief of staff of Iran’s armed forces, Masoud Jazayeri, threatened to destroy Israel should the United States launch bombing raids against Iran. “They (the United States) know that aggression against the Islamic Republic of Iran would mean annihilation of Tel Aviv and the spread of war into the United States,” he warned.

The warning may be nothing more than bluster, but it should be taken seriously because Iran would not turn the other cheek if bombed and would fire a barrage of long-range missiles at Israel.

This past spring, websites in Iran carried a four-minute Persian-language animated film showing how an Iranian reprisal mission against Israel would unfold. The video, one of several on the topic that have surfaced in recent years, is fanciful, theatrical and eerie.

No one, however, should discount the possibility that Iran, if unilaterally struck by Israel or the United States, would hit back in extreme anger.