Proceeding on the assumption that the best defence is a good offence, President Barack Obama has launched an aggressive public relations campaign to sell the Iran nuclear agreement to the divided U.S. Congress.

Congress has until September 17 to review the controversial accord and decide whether it should be approved or rejected.

The Republican Party, which holds a majority of seats in the Senate and the House of Representatives, staunchly opposes it and will try to scuttle it. Obama, a Democrat, has promised to veto a Republican motion of disapproval, but if two-thirds of lawmakers come out against the agreement, they can override Obama’s veto, thereby dealing him a crushing blow.

Vigorously denounced by Israel as a threat to its long-range security, the accord was signed in Vienna on July 14 by the six major powers — United States, Russia, China, Britain, France and Germany — and Iran after almost two years of negotiations. In exchange for curbing its nuclear program for the next 10 to 15 years and agreeing to have it monitored for violations by international inspectors, Iran will receive sanctions relief to the tune of $50 billion to $150 billion.

Having described the agreement as a “very good deal,” the Obama administration claims it cuts off all pathways for Iran to develop an atomic arsenal.

Sharply disagreeing with Obama’s interpretation, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has lambasted it as “a very bad deal” and an “historic mistake” because it leaves Iran’s nuclear infrastructure basically intact, though frozen, and allows Iran — the preeminent Shiite state in the region — to increase its influence in the Middle East and continue to support anti-Israel proxies like Hezbollah and Hamas.

Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Khamenei, has portrayed the agreement as a triumph for Iran. Thousands of centrifuges refining uranium are still spinning in Iran, he boasted on July 18.

Although rival Sunni Arab states like Saudi Arabia and Egypt are uneasy about it, they have refrained from publicly criticizing it, leaving that role exclusively to Israel. As a result, as Obama pointed out, Israel is the only country in the world attempting to derail it.

Nearly 35 years ago, in its last sustained effort to foil a U.S. foreign policy initiative, Israel tried to undo a plan by the Reagan administration to ship advanced F-15 fighter jets to Saudi Arabia, which is still technically at war with Israel.

The Israelis lost that battle.

In its campaign to kill the agreement, Israel can count on the Republicans, who oppose it unanimously. Israel hopes it can also convince wavering Democratic senators to make common cause with the Republican Party on this contentious issue. Yesterday, Charles Schumer, the influential senator from New York, announced he would vote against it.

Netanyahu, in a video conference this week, urged American Jews to come out against this “dangerous deal.” And while some Jewish federations and Jewish groups, like the American Jewish Congress and the American Israel Public Affairs Committee, have heeded his call, the prime minister’s confrontational stance has created a sense of unease.

In an implicit reference to Netanyahu, Malcolm Hoenlein, the executive vice-president of the Conference of Presidents of Major American Jewish Organizations, said that Israeli governments “should not be telling American Jews what to do vis-a-vis their government.”

Given the fierce opposition the agreement has engendered, the Obama administration has deployed its biggest guns to ensure that it passes muster.

Obama, who has categorically pledged to stop Iran from building a nuclear bomb, has taken the lead in defending the agreement. In a combative speech at American University in Washington, D.C., he said, “Let’s not mince words: The choice we face is ultimately between diplomacy and some sort of war — maybe not tomorrow, maybe not three months from now, but soon. How can we in good conscience justify war before we’ve tested a diplomatic agreement that achieves our objectives?”

Obama, having stressed that it is based on verification rather than trust, told Jewish community leaders in the White House recently that failure to ratify it would be disastrous.

If the agreement is shot down and the United States is pressured to bomb Iran’s nuclear sites, he warned, Iran’s proxies will attack American and Israeli targets. “They will fight this asymmetrically,” he said. “That means more support for terrorism, more Hezbollah rockets falling on Tel Aviv.”

Obama added that Israel would “bear the brunt” of an asymmetrical response orchestrated by Iran.

American Secretary of State John Kerry, the chief U.S. negotiator at the nuclear talks, has weighed in as well. Last month, in an ominous warning, he said that Israel risks isolation and blame should Congress overturn the agreement. On August 5, he introduced a new element into his reasoning, suggesting that Iran’s threats to destroy Israel may be overstated. While Iran is ideologically hostile to Israel, the Iranian regime has not taken “active steps” to try to attack Israel directly, he claimed.

In Kerry’s estimation, the agreement is as “pro-Israel, as pro-Israel’s security, as it gets. And I believe that just saying no to this is, in fact, reckless.”

Netanyahu vehemently disagrees with the overall U.S. assessment.

Calling the agreement fatally flawed, Netanyahu said it paves rather than blocks Iran’s path to a nuclear bomb. And the agreement endangers Israel’s survival and destablizes the region, he noted. “This deal will bring war,” he claimed. Whether the Iranians honor or break the deal, Iran will eventually acquire “hundreds of bombs,” he predicted.

Presenting an alternative to the agreement, he said, “Increase the sanctions, increase the pressure.” Iran, he stated, should dismantle its nuclear infrastructure in return for sanctions relief. “That was the original (U.S.) position and I think it was the right one.”

According to Netanyahu, Iran would abide by more stringent limitations on its nuclear program, which, Tehran claims, is for peaceful purposes.

In a bid to mollify Israel, the United States has promised to upgrade Israel’s defences. Obama has said he’s prepared to hold “intensive discussions” with Israel to bolster its armed forces.

Two months ago, General Martin Dempsey, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, assured Israel that the United States will maintain its qualitative military edge over its adversaries. And he reminded his Israeli interlocutors that Israel will be the first Middle Eastern nation to take delivery of the new and advanced F-35 stealth jet.

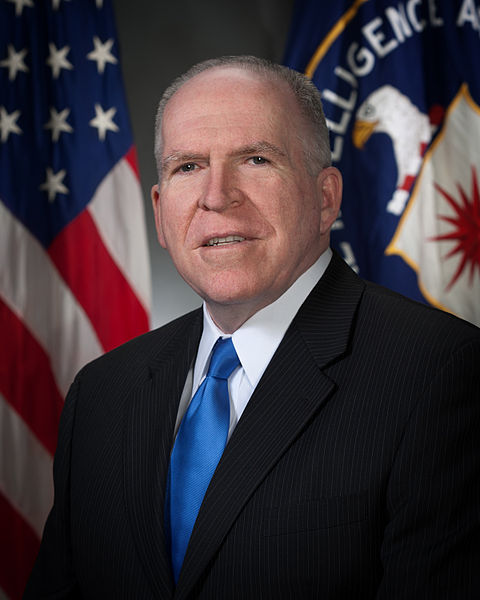

In a visit to Israel on the eve of Dempsey’s trip, John Brennan, the director of the Central Intelligence Agency, offered Netanyahu similar assurances.

Visiting Israel in July, Ashton Carter, the U.S. secretary of defence, pledged that the United States will combat “Iran’s malign influence” in the area.

As expected, Netanyahu has dismissed Washington’s charm campaign.

“Everybody talks about compensating Israel. If this deal is supposed to make Israel — and Arab neighbors — safer, why should we need to be compensated with anything? And how can you compensate my country against a terrorist regime that is sworn to our destruction and going to get a path to nuclear bombs?”

Echoing Netanyahu’s comments, Israel’s deputy prime minister, Silvan Shalom, said, “If the agreement is so good, and if the agreement is making sure the Iranians will never have nuclear power, why we we need any kind of aid?”

Observers do not regard their remarks as Israel’s final word on the subject. If the agreement becomes a fait accompli, as it likely will, Israel will demand significant compensation from the United States.

Even if the agreement is ratified by Congress, Iran is unlikely to modify its belligerent attitude toward the United States. Speaking in Tehran last month, Khamenei declared that it will not end the hostility between Iran and the United States. “Their actions in the region are 180 degrees different from ours,” he asserted.

Nor does Iran intend to moderate its stance on Israel.

Last month, during a visit to Iran to promote trade, German Vice Chancellor Sigmar Gabriel admonished his hosts by saying that Germany could not accept Iran’s belligerency toward Israel.

He was roundly rebuffed by an Iranian Foreign Ministry official. “We have totally different views from Germany on certain regional issues in the Middle East, and we have explicitly expressed our viewpoints in different negotiations,” said Marziyeh Afkham, demolishing Gabriel’s overture.

Iran is talking tough, but so is Israel.