Sunday, July 23, 1944 was the blackest of days for the Jews of Rhodes, a mountainous island in the Aegean Sea eighteen kilometres off the coast of Turkey. On that catastrophic day, during the final ten months of World War II, the German occupiers set off air raid sirens to keep its residents indoors so that they would not witness the deportation of the island’s 1,650 Jewish inhabitants.

Having been packed into three boats, the Jewish deportees were taken to the Greek port of Piraeus and then to a prison at Haidari. From there, after three days of incarceration, they were loaded on to trains bound for the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp in Poland.

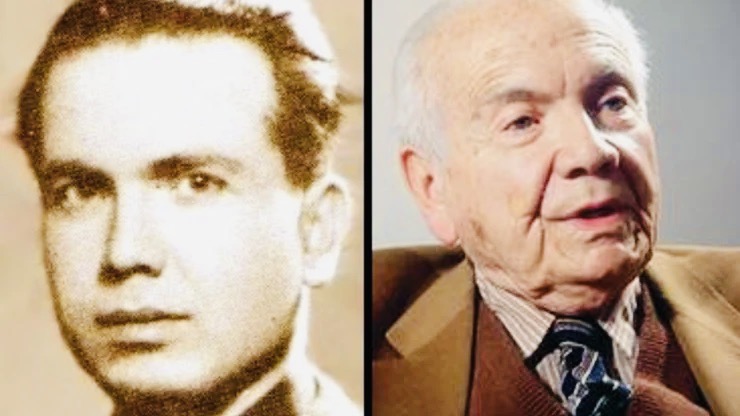

Among the passengers on the tortuous two week journey was Stella Levi, a young woman who managed to survive the ordeal. Several years ago, in the comfort of her home in New York City’s Greenwich Village, she recounted her story to journalist Michael Frank over one hundred Saturdays during the course of six years. They had been introduced to each other by the director of the Centro Primo Levi in Manhattan.

Born a century ago this year, she was not keen to be interviewed. But because she was one of the last Jews of Rhodes, the largest island in the Dodecanese chain of islands, she agreed to talk to Frank. In his book, One Hundred Saturdays: Stella Levi And The Search For A Lost World (Avid Reader Press), he describes her as a “Scheherazade” and “a witness” who would take him back in time to an ancient Jewish community that the Nazis uprooted and destroyed within a matter of weeks.

The illuminating volume under review, which is adorned by the vibrant drawings of Maira Kalman, is composed of two segments. The first is a snapshot of the Juderia, the atmospheric neighborhood in the town of Rhodes where Levi was born and raised. The second recounts the Italian and German occupations, the tragic deportation, and Levi’s postwar life abroad.

Frank believes she will always be in exile. After her liberation, she was reunited with the remnants of her family in Los Angeles. But not feeling at home there, she went to Israel, only to pack up and leave. “She is most at home in New York, she says, because New York is itself made up of so many exiles, so many wanderers like herself,” he writes.

Rhodes, an island of 1,400 square kilometers, was administered by the Ottoman Turks for hundreds of years before its conquest by Italy in 1912. In addition to Rhodes, which Levi dismisses as “a small island in the middle of nowhere,” Italy ruled the nearby islands of Kos, Patmos and Leros.

In 1948, Israel and several Arab countries signed armistice agreements in Rhodes.

Levi hails from a big family. One of seven siblings, she had two brothers, Victor and Morris, and four sisters, Selma, Felicie, Sara and Renee. Several left Rhodes before the war. Their father, Yehuda, was a successful supplier of wood and coal.

Known as Rhodeslis, Jews shared the island in relative harmony with Greeks and Turks. During Passover, some Greeks threw stones at Jews in the bizarre belief that they used Christian blood in the baking of matzahs. This medieval superstition seems to have petered out when Levi was a teenager.

The Juderia, encompassing about eleven blocks, was alive with “scent, color, taste, movement and sound,” Frank notes. It was a tight-knit Jewish community. Levi’s father never regarded himself as Italian or Turkish, but exclusively as Jewish. Even though Levi grew up to be a non-believer, she identified herself as Jewish. “It was her Judaism, which organized the weeks, the seasons, the holidays — their whole lives, their own world.”

Its inhabitants spoke Judeo-Spanish, or Ladino, but Levi’s maternal grandmother spoke Turkish and some Greek.

Housewives like Levi’s mother, Miriam, took their dishes to communal ovens and gossiped with friends as they waited for the food to be cooked. Vegetables were the foundation of their diet, but burekas, savory pastries with a variety of fillings, were popular. Sabbath meals included fresh fish or chicken. Desserts tended to be fresh or candied fruits.

Since they had no baths or showers in their homes, people went to Turkish baths. In accordance with their affinity for Spanish culture, they sang Spanish romansas.

Levi’s older siblings attended an Alliance Israelite Universelle school, where French was the language of instruction. Levi went to an Italian school, adored Italian and aspired to visit Italy. Virtually no one in her social circle in Rhodes spoke English.

As Frank suggests, the Italians were a modernizing force insofar as Jews were concerned, bringing electricity, running water and sewage pipes into the Juderia, which the king of Italy, Victor Emmanuel III, visited in 1929. In his honor, Turkish carpets were laid down in the piazza.

Throughout the rest of Rhodes, Italy paved roads, drained swamps, planted forests, built luxury hotels, constructed the first modern hospital, and granted citizenship to children born after 1923. These projects were instrumental in gradually erasing Turkish influence. Before the arrival of the Italians, Levi’s father wore a fez to work and was essentially a Turk in terms of language and culture. But “month by month, year by year, these lingering traces of the old world began to recede,” says Frank.

With the introduction of fascist Italy’s antisemitic laws in 1938, Jews like the Levis were singled out for persecution. Around 500 Jews who had settled in Rhodes after 1919 were ordered to leave. Eventually, some of the anti-Jewish laws were relaxed, enabling Jews to frequent movie theatres and the beach.

Wealthy Jews, having read the writing on the wall, departed in 1938 and 1939, settling in Paris, Tangier, Cairo and elsewhere. The Levis tried to immigrate to the United States, but were unable to obtain entry visas.

With the ouster of Italian ruler Benito Mussolini in July 1943, the status quo remained in Rhodes. But after Italy’s provisional government declared a truce with the Allies in September of that fateful year, Germany invaded Rhodes. The Italian military garrison fought back, but surrendered.

The Germans allowed the Italian bureaucracy to function and, for a while at least, life returned to normal. The synagogues stayed open, residents of the Juderia were left in peace, and the existing racial laws were not expanded, Levi recalls. “This was our new reality, and we simply lived it.”

In 1944, British aircraft bombed Rhodes, accidentally killing civilians. In February, eight Jews in the Juderia were killed. And in April, twenty six Jews were killed near the synagogue. These air raids prompted the Levis to leave the Juderia and rent a house in a nearby Greek village.

On July 19, 1944, the German ordered Jewish males over the age of thirteen to present themselves with their documents at the former headquarters of the Italian Air Force. “We still — still — had no idea why they were collecting us,” says Levi. “Anyway, we did as we were told.”

One by one, almost every Jew turned up. Fifty Jews, some of whom were Turkish citizens, were exempted from the order. They were rescued by Turkey’s consul, Selahattin Ulkemen. “Some came to him. Some were brought to his attention.” The Germans did not, as a rule, deport Jews from neutral countries.

The Jews selected for deportation were instructed to keep their eyes on the ground as they were escorted through the town by German infantrymen and Italian police. “No one was there,” says Levi. “No one watched, No one protested.”

It took several hours for all 1,650 Jews to reach the port, where three dilapidated cargo vessels were anchored and waiting. The deportations were carried out with the full complicity of Italian authorities, who had prepared a list of Jews in Rhodes.

To this day, Levi cannot understand why the Germans spent so much time, money and energy to round up Jews.

The journey from Rhodes to Piraeus lasted eight days. Conditions were deplorable and food and water were in short supply. En route to Greece, five people died, their bodies thrown overboard. At Leros, another boat carrying about one hundred Jews from the island of Kos joined their vessel.

Levi still wonders why Turkish and British ships in these waters permitted the deportations. She claims she had no idea what the Germans intended to do to them. “We thought, ‘Oh, we’re going to another island. We’re going to a work camp. All this is temporary. We’ll be back, of course.'”

On August 3, the Jews of Rhodes, plus hundreds of Jews from near Athens and from Kos and Leros, were transferred to a train. At the last possible moment, Ulkemen, the Turkish diplomat, saved the son of Alberto Franco, the president of Rhodes’ Jewish community. He was married to a woman of Turkish nationality.

The train passed through Greece, Yugoslavia, Hungary and Czechoslovakia before reaching Auschwitz-Birkenau, a place the Jews of Rhodes had never heard of, on August 16. Right away, SS guards separated men from women. Levi’s parents were sent to the gas chambers. She and her sister, Renee, and their cousin, Sara, stayed together. Levi stopped thinking after arriving in Auschwitz-Birkenau. “It was too dangerous to think,” she told Frank. Levi also detached herself from her former self to survive.

“Overnight, it seemed, she turned into someone who robbed, cheated, connived, was suspicious, vigilant, devious, sly. She did whatever it took to keep herself going every day.” But she was often profoundly hungry.

After Auschwitz-Birkenau, Levi was moved to a succession of camps, including Dachau and Turkheim. When she was liberated, she weighed less than eighty pounds. “Once we realized we were free, we fell to our knees and started weeping,” says Levi. “We came back to ourselves, we became human once more.”

During the next few months, Levi lived in Italy, the land of her dreams. But on November 19, 1946, she and Renee boarded a ship bound for New York, where they stayed with cousins. Then they went to Los Angeles, the home of their brother Morris. Their very presence made the Holocaust in Rhodes viscerally real to Morris and his family. “They cried for the loss of our home, the death of our parents, the end, well, of everything they had grown up with, everything we had grown up with …”

Neither Levi nor her sister liked Los Angeles, but it was there that they took their first English lessons. They intended to return to Italy, but a friend convinced them to rebuild their lives in New York. Levi found a job as an administrator in an import-export company. Later, she established her own business.

She met a man whom she married and with whom she had a son in 1954, but their marriage collapsed after three years. From that point onward, her most significant and enduring relations were her friendships.

Levi visited Rhodes in 1977, the first of several trips to the island, but she felt like a foreigner there. The Juderia, once the hub of the Jewish community, was bereft of Jews and had degenerated into a cheesy tourist attraction. A memorial in the piazza, inscribed in Greek, Hebrew, Judeo-Spanish, English, French and Italian, pays tribute to the victims of the Holocaust in Rhodes and Kos.

One Hundred Saturdays: Stella Levi And The Search For A Lost World beautifully and sorrowfully resurrects this chapter in Jewish history.