Al Jolson was in a class all by himself.

From about 1912 until 1934, he was the most highly paid entertainer in the United States. What Enrico Caruso was to opera, Jolson was to popular song.

Jolson’s friend, the comedian George Burns, once said, “There was nobody as good as Jolson. When he got through, you forgot there had been anybody on before him.”

A slim, ordinary-looking man of colossal energy, ambition and ability, Jolson was a star of musical theater on Broadway and appeared in The Jazz Singer (1927), the first feature-length movie with synchronized music and dialogue.

Born in 1886 in a shtetl in Lithuania, then a colony of the Russian empire, he arrived in the U.S. at the age of nine, in the last decade of the 19th century. His name back then was Asa Yoelson. Within 15 years, he had transformed himself into one of the most famous people in America.

“Jolson’s story is the American immigration story at its best, the escape from a place where a rise to fame and fortune like this would have been impossible to a place where such a rise defined what the country considered special about itself,” writes his biographer, Richard Bernstein, in Only in America: Al Jolson and the Jazz Singer, published by Alfred A. Knopf.

As he points out in this fast-moving and absorbing volume, Jolson was part of a cohort of entertainers whose roots were in Eastern Europe and who came nearly to dominate American popular culture in the first half of the 20th century. “It’s hard to imagine anything like that happening any place but in these United States of America,” says Bernstein, a former foreign correspondent of The New York Times who died recently.

In the early years of the last century, he notes, approximately half of the entertainers in New York City were Jewish. It was “an avenue open to them,” at a time when the arrival of so many Jewish immigrants had aroused a wave of antisemitism.

Jolson was born in Seredzius, a village in the Pale of Settlement, a region to which virtually every Russian Jew was restricted during the czarist period. It encompassed much of present-day Lithuania, Ukraine, Belarus and Poland.

Moshe, his father, was a rabbi and a cantor. Expecting him and his brother to emulate him, he trained them in voice, thereby unwittingly preparing them to be stage performers. Moshe immigrated first, leaving his family behind in Seredzius until 1894.

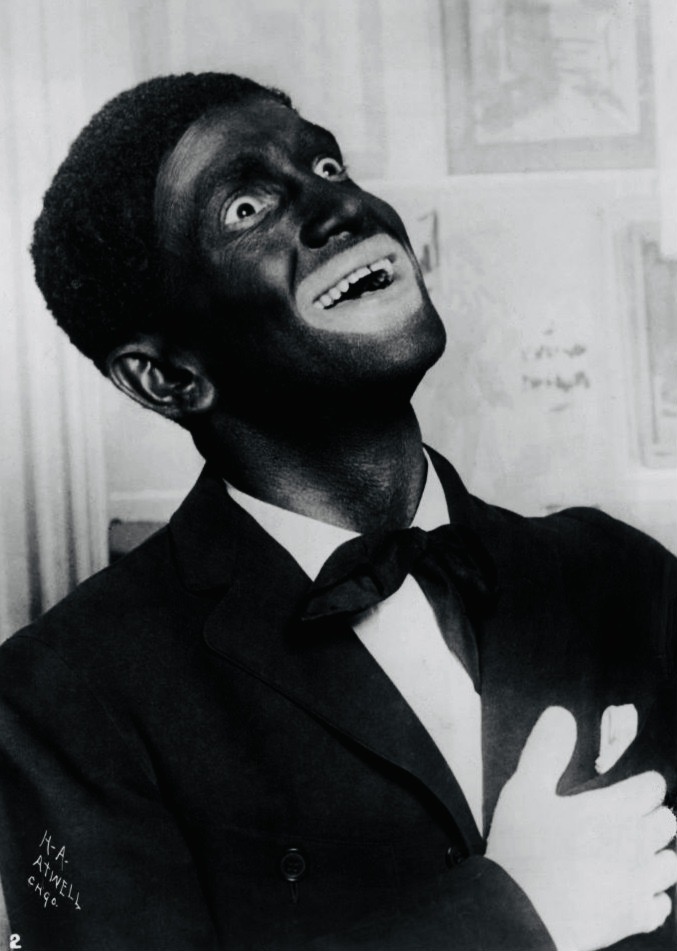

Jolson and his brother, Harry, became entertainers in a subculture of street performance, vaudeville, burlesque, nickelodeons, saloons, restaurants and beer parlors. When they came of age, show business was a lucrative industry. Jolson started off as a singing comedian who often performed in blackface, which, while unacceptable today, was very common more than a century ago.

As Bernstein observes, “The mere fact that … Jolson could take on the persona of a black man and play him over and over again … was surely rooted in the pathological fixation of white America on blackness, which made minstrelsy the most popular form of entertainment in the country from roughly the mid-nineteenth century to the early decades of the twentieth.”

Exploring this idea further, he speculates that blackface enabled Jews “to conceal their Jewishness” and “assert their whiteness” so as to be fully accepted as Americans.

In tracing the arc of his career, Bernstein states that he broke into stardom when Jesse Lasky, an up-and-coming entertainment agent and a future Hollywood studio boss, discovered him during a blackface routine.

By 1918, he was earning at least $2,500 a week, a sum beyond the imagination of an ordinary worker.

Jolson’s technique on stage was unique. He ran back and forth on a runway into the lap of the audience, got down on one knee, extended his white-gloved hands, and belted out the final refrain of a song. The corny songs inextricably associated with him were “Swanee,” “My Mammy,” “Toot Toot Tootsie,” and “Rockabye Your Baby With A Dixie Melody.”

In Bernstein’s estimation, there was nobody in entertainment until the late 1940s more in demand and celebrated than Jolson. “His voice had a broad range, an instantly recognizable timbre, a vibrato, that set him apart.”

Bernstein explores Jolson’s participation in The Jazz Singer, the first “talkie,” at length.

Based on “Day of Atonement” a short story by Samson Raphaelson, it appeared in the 1922 edition of Everybody’s Magazine, a general interest publication. Subsequently crafted into a Broadway play, it turned on an intergenerational conflict between a father and a son and tradition and modernity.

While most Hollywood studios were content with the status quo, the profitable business of churning out silent movies, Warner Bros. took a big financial risk in converting “Day of Atonement” into a sound movie. Bernstein patiently explains the technical problems that had to be resolved to achieve this objective.

When Jolson accepted the lead role in The Jazz Singer, Bernstein says, he moved closer to his ancestral roots. “Everybody knew that Jolson was Jewish, foreign-born, and the son of a cantor … Here and there in his stage appearances he’d make a gesture of complicity with the Jews in the audience by letting fly a little Yiddishism … Jolson never concealed his Jewishness, but in public he mostly kept it in the background.”

But now, in The Jazz Singer, which was drawn from Jolson’s own life and would celebrate the haunting beauty of cantorial music, he could be Jewish in the full sense of the word. Bernstein believes that the film was “a kind of religious coming out,” not only for Jolson but for the Warner brothers, who strove for assimilation and acceptance in American society.

Given the antisemitic prejudices of the day, Jewish themes had always been a minor element in Hollywood movies. With the notable exception of light comedies such as Sailor Izzy Murphy and Clancy’s Kosher Wedding, producers had stayed clear of Jewish characters and story lines.

The Jazz Singer, with its scenes of caftan-clad rabbis and cantors and the chanting of Kol Nidre in an actual Orthodox synagogue, was the striking exception in 1920s America, a nation where the Ku Klux Klan reigned supreme and Jews were often treated like second-class citizens.

“The Warners knew the anxiety of being Jewish in America in 1927, but they had succeeded there, and they had a certain confidence that The Jazz Singer would make its way,” writes Bernstein. “And, as it turned out, they were right. Or perhaps they were just lucky that the movie came out when America was becoming the best place in the world for Jews.”

The film was a box-office hit, “the big new thing.” Capitalizing on its astounding success, Jolson starred in a succession of movies ranging from Say It With Songs in 1929 to Mammy in 1930.

By 1932, he had switched to radio, the hottest new medium, as his principal vehicle. During World War II and the war in Korea, he performed for U.S. troops.

On September 4, 1941, the Jewish inhabitants of Seredzius, numbering 198 in total, were murdered by the Nazis. “But for the lucky fact of his departure, he would have been murdered by the banks of the Nieman River …”

Jolson married his third wife, a nurse who was young enough to be his daughter, in 1947, three years before his death. Like his two ex-wives, she was a gentile. In the same year, he sold The Jolson Story to Colombia Pictures. A sensation, it was the fifth biggest grossing movie of the year.

In summing up his life, Bernstein is succinct. “Two conditions were necessary for Jolson and (American) Jews to arrive at their destination: talent and freedom. Jews like Jolson had the one. America gave them the other.”