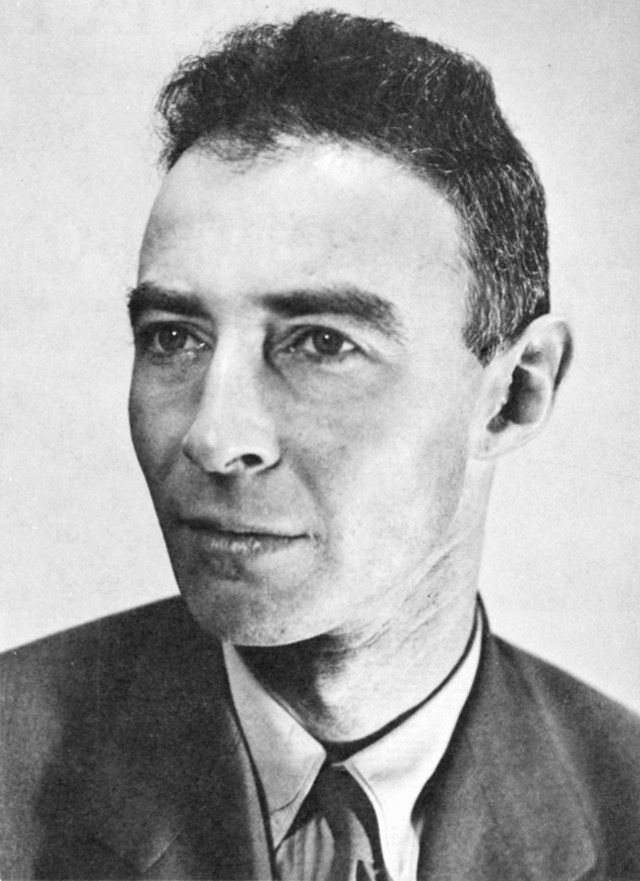

Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer, which I recently had the pleasure of watching, paints a vivid and sympathetic portrait of the brilliant American theoretical physicist whose stellar scientific team created the first nuclear weapon.

This 179-minute feature film, the winner of seven Academy Awards in 2023, focuses on Julius Robert Oppenheimer, the director of the Manhattan Project. It was established by President Franklin Roosevelt to ensure that the United States did not fall behind Nazi Germany in the race to build a nuclear device.

Albert Einstein, the famed German Jewish physicist, convinced Roosevelt that the fate of Western democracies rested on America’s ability to surpass Germany in that crucial competition. Washington invested $2 billion, a fantastic sum back then, to construct Los Alamos, a town in a remote corner of New Mexico where some of the world’s finest scientists gathered to complete the mission.

Oppenheimer arrived in 1942 to oversee it. Within three years, a nuclear bomb has been assembled to be used against Japan, the last Axis holdout. Atomic bombs were dropped on the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, wiping out tens of thousands of lives and forcing Japan to surrender unconditionally.

Oppenheimer, starring the Irish actor Cillian Murphy as the Jewish American physicist who brought the project to its successful completion, mostly oscillates between World War II and the postwar period.

Apart from Oppenheimer, the main characters are Leslie Groves (Matt Damon), the U.S. general to whom he reported; and Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey Jr.), the director of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, who, after the war, invited Oppenheimer to work at the Institute of Advanced Study at Princeton University.

Famous scientists, ranging from Edward Teller to Isidor Isaac Rabi, appear and reappear as the project gains momentum.

From the outset, Oppenheimer believed that Nazi antisemitism gave the U.S. an immediate edge over Germany’s nuclear program, which was headed by the physicist Werner Heisenberg. Adolf Hitler, the German chancellor, apparently blocked vital funds to Heisenberg due to his misguided belief that quantum physics was a “Jewish” science. Little did he know that, absent this discipline, an atomic bomb would have remained a figment of the imagination.

Still, some American scientists were reluctant to weaponize physics. Even Oppenheimer was plagued by doubts, fearing that a nuclear explosion might ignite and destroy the universe. Teller triggered another debate with his proposal to use hydrogen rather than uranium and plutonium to develop an atomic bomb.

Although the Soviet Union was America’s ally during the war, Oppenheimer refused to share nuclear secrets with the Russians. “That would be treason,” he says. When he learned that the Soviets were busy working on a hydrogen bomb, he grew concerned whether a Russian spy was employed on the premises.

Oppenheimer’s fears segued into the Red Scare phenomenon in America, a key theme in the film. While he was never a member of the American Communist Party, he had read the works of Karl Marx and held left-of-center views. In addition, his wife had been or was still a communist and his mistress was drawn to communism. As a result, he came under grave suspicion. Groves may have had misgivings about Oppenheimer’s politics, but he gave him a security clearance because he knew he was an indispensable asset.

The film reaches a crescendo when Oppenheimer and his colleagues test the A-bomb after an agonizing delay caused by poor weather. In sequences brimming with high drama, the explosion produces a molten fireball, a red hot blast of ear-splitting thunder.

“It worked,” exclaims a technician in an understatement. Oppenheimer nods his head. And then cheers erupt.

“The world will remember this day,” Oppenheimer murmurs, adding he would have preferred to drop the A-bomb on Germany.

In a celebratory moment, he meets President Harry Truman at the White House, but the meeting ends awkwardly when Oppenheimer calls for Los Alamos’ eventual closure and expresses guilt of having “blood on his hands.”

After the war, Oppenheimer’s security clearance was not renewed, his loyalty to America having been questioned. A government panel cleared him of disloyalty, but removed his security clearance, thereby tarnishing his reputation.

Strauss, having been politically tarred by his association with Oppenheimer, was denied a seat as commerce secretary in President Dwight Eisenhower’s cabinet. He, too, was a victim of the McCarthyist era.

Oppenheimer, distinguished by superior performances from its accomplished cast, deals with all these issues competently, wrapping them up in a seamless and appealing package.