Israel, in many respects, is a shining beacon of openness and tolerance. Judging by its multiplicity of political parties, its transparent governing institutions and its splendid arts scene, Israel is far and away the most vibrant democratic society in the Middle East.

Yet Israel’s body politic is sullied by an unsightly stain. Since the advent of Israeli statehood, the Orthodox rabbinate, in collusion with the government, has had a grossly unfair and unreasonable monopoly over life-cycle events from marriage to divorce and over conversion, an issue that has been in the news of late.

Last week, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s government annulled a measure to ease the conversion process. By doing so, he probably made it harder for tens of thousands of immigrants to convert to Judaism. Though strongly endorsed by middle-of-the-road ministers when it was approved by the cabinet in 2014, the measure was not passed into law by the Knesset.

Following the last general election in March, Netanyahu signed coalition agreements with two haredi parties — Shas and United Torah Judaism — which had been excluded from his previous cabinet. As part of their price for joining his minority government, Shas and United Torah Judaism demanded that the initiative be stricken from the government’s agenda.

Netanyahu, though secular and probably personally sympathetic to a more liberal conversion procedure, caved in and agreed to abide by their demand. No surprise here. Political survival is, after all, Netanyahu’s credo.

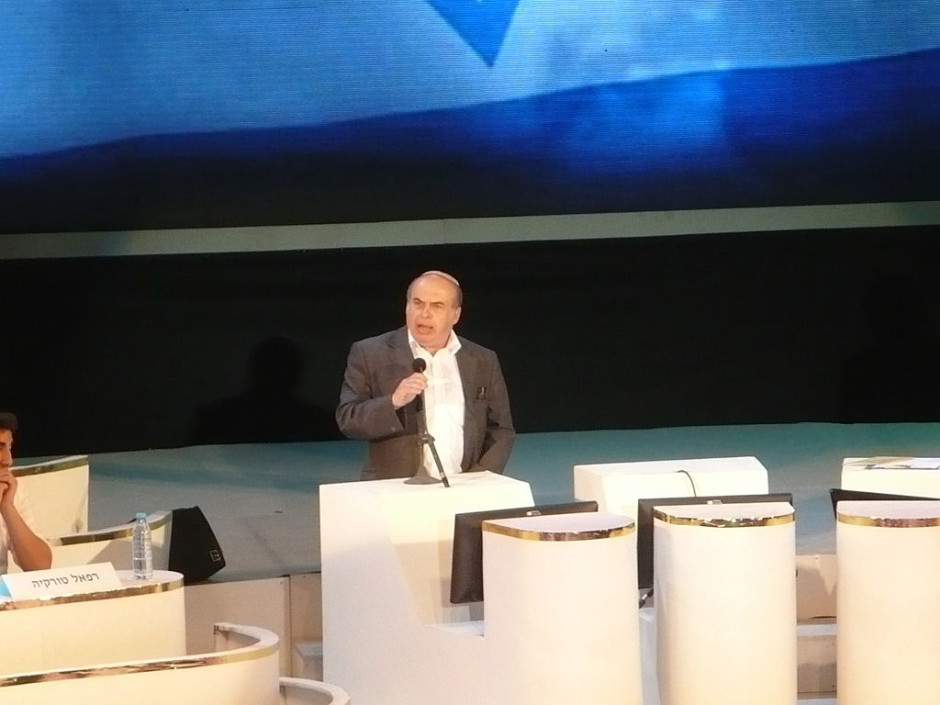

Such issues, however, should not be contaminated by political horse trading. As Natan Sharansky, the chairman of the Jewish Agency, recently observed, “We cannot accept the fact that a matter so vital to the future of the Jewish people and to Israel’s existence as a Jewish state is subject entirely to the configuration of the coalition at any given time…”

Sharansky, of course, was referring to the now dead conversion measure, which would have benefited as many as 300,000 immigrants from the Soviet Union/Russia. The descendants of mixed marriages, or the Christian spouses of Jews, they find themselves in an uncomfortable twilight zone, with one foot in Israel and another in Russia. It’s questionable whether Israel can fully integrate this sector of the population unless they’re given the opportunity to convert to Judaism in a process that respects their backgrounds and is not overly stringent.

Regrettably, the religious question bedevils Israel across the board.

Outrageously enough, the Israeli minister of religious affairs, David Azoulay, a member of the Shas faction, continues to rail against the Reform branch of Judaism, to which many American and Canadian Jews belong.

Last month, he was quoted as saying that Reform Jews are “a disaster to the nation of Israel.” Several days ago, he declared, “I cannot allow myself to call such a person a Jew.”

It’s bitterly ironic that Israel is the sole country in the world where a government minister can denigrate Reform Jews with impunity and where Reform Jews are made to feel like outcasts.

Netanyahu disavowed Azoulay’s hateful and ignorant remarks, saying they do “not reflect the position of the government,” and adding that Israel is “a home for all Jews.”

Netanyahu’s rebuke should be taken with a large grain of salt, since Shas’ inclusion in his government enables hatemongers like Azoulay to spew their venom on an official basis. But let’s be clear. Azoulay represents the tip of an iceberg in Israel. Long before he was appointed Israel’s president, Reuven Rivlin, a supposed liberal, described Reform Judaism as “idol worship and not Judaism.”

Israel cannot truly be a modern and progressive state unless it drastically reduces the power of the rabbinate, breaks its monopoly over religious matters and equalizes the status of Reform — and Conservative — Judaism with that of the Orthodox stream.

Better still, Israel should seriously consider the possibility of ultimately separating synagogue and state. Politics and religion do not mix and never have.

Let the debate begin.