Outremont, a sedate and generally affluent neighborhood in the center of Montreal, is embroiled in a running dispute regarding its willingness to accommodate its tight-knit, insular ultra-Orthodox population. This divisive issue has stamped Outremont as a place of conflict, laments its mayor, Philipe Tomlinson.

The majority of Outremont’s French and English residents do not appear to have a problem with the 7,000 haredim, who represent 23 percent of its population. But a few vocal French Canadians have complained about them.

Eric R. Scott’s nuanced documentary, Outremont and the Hasidim, delves into this complex controversy. It will be screened online by the Toronto Jewish Film Festival, which runs from October 22 to November 1.

Scott interviews a wide variety of people in and out of the ultra-Orthodox community. They run the gamut from Pierre Lacerte, a blogger who claims that its leadership does not respect the law, to Mayer Feig, a haredi spokesman who believes that critics like Lacerte are “squeezing” them, “twisting the facts,” or engaging in outright lies.

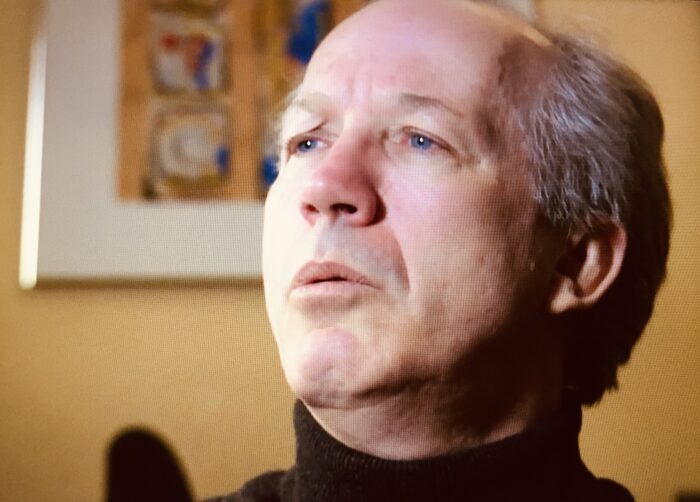

Lacerte contends that the haredim have built illegal dormitories and synagogues. He predicts that the ultra-Orthodox “ghetto” will continue to grow and eventually displace non-Jews in Outremont.

A woman, a French Canadian shopkeeper, claims they have changed the “look” of Bernard Street, Outremont’s main thoroughfare. She argues that their synagogues should be built only on side streets.

Still another French Canadian woman, a sociologist, contends that the ultra-Orthodox as a group are aloof and distant and refuse to integrate into the mainstream community. “They do not see us,” she says. “We do not exist. Only they exist and we do not.”

In 40 years, she adds, not a single member of this community has ever said hello or attempted to communicate with her. She insists that she is not antisemitic, and that she only wishes to achieve “harmonious community life” in Outremont.

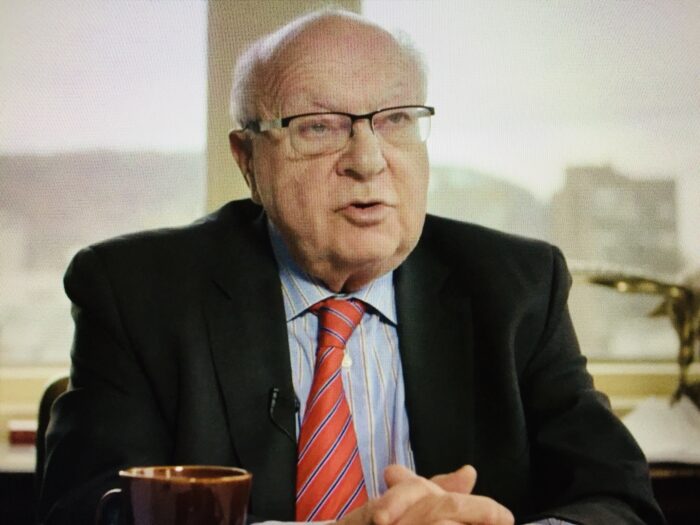

Julius Grey, a Jewish lawyer who has represented the ultra-Orthodox in courtroom battles, ascribes intolerance toward them on the grounds that die-hard secular Qubecois are alienated by their strong religious beliefs.

Still other French Canadians are more open to them.

Tomlinson, the mayor, thinks the two communities should be able to coexist, notwithstanding their radically different lifestyles.

Local resident Michele Dupont says, “I want to live well with my Hasidic neighbors. I would like to know them a little more.”

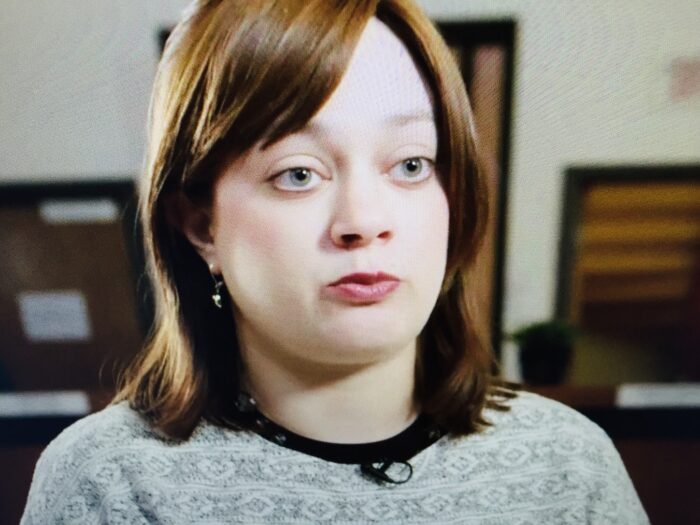

Mindy Pollak, a municipal counsellor who belongs to the haredi community, contends that her community has demanded equal rather than special treatment. The grand-daughter of Holocaust survivors, she readily admits that some of her confreres are socially challenged. Other haredim are opposed to forming relations with non-Jews because they’ve been traumatized by the Christian betrayal of Jews during the Holocaust.

A young haredi Jew, a member of the Belz sect, acknowledges that some of his contemporaries are indeed unfriendly, but his friend begs to differ. “Our Quebecois neighbors don’t understand us,” he says. “There are reasons behind the things we do.”

And so the standoff between the haredim and the rest of the community simmers, causing tensions that linger on and fester, to the detriment of both communities.