Panama, the lower-cost alternative to Costa Rica, is a land of sharp and mesmerizing contrasts.

One day, I was perspiring in the sweltering tropical lowlands of Chiriqui province, or exploring a picturesque island in the Bocas del Toro archipelago in the Caribbean Sea.

A few days later, and just a relatively short distance away, I was exploring the town of Boquete, where the temperature at night can drop to freezing.

After flying into Panama City from Toronto, I started my tour of this geographically diverse nation at the Alouatta Lodge & Rescue Center. Thirty minutes by bus from David, a forgettable flyblown town in Chiriqui — a lush and hilly region dotted with farms and cattle ranches — Alouatta is a rehabilitation center for howler monkeys, and apparently the only one of its kind in the Americas.

Founded in 2008 by Steve and Michelle Walker, an Australian couple, Alouatta sits on the summit of a thickly-forested mountain with tantalizing views of the Pacific Ocean. My daughter and I arrived Alouatta after a bone-rattling ride in the back of a pickup truck.

An oasis of well-tended botanical gardens and groomed paths cutting through a virgin tropical rainforest, Alouatta’s beauty struck me immediately

The Walkers came here with the intention of rescuing orphaned howler monkeys, which are indigenous to Panama. They rescue and rehabilitate monkeys whose pet owners have either abandoned them, or whose mothers have been killed for bush food.

Michelle, a spunky woman who takes care of these creatures with tender, loving care, said, “We’re here to keep them strong and healthy before we release them into their natural habitat in the forest.”

When we visited Alouatta, eight howler monkeys were roaming the grounds. Being people-friendly, they are allowed to interact with visitors and be cuddled, but not held tightly. If their movements are restricted, we were told, they may bite. So beware.

The Walkers also keep several Geoffroy’s tamarin monkeys in cages. Indigenous to the primary forests near Panama City, the capital, and the Darien Gap, in southern Panama, they’re caged because they can be vicious.

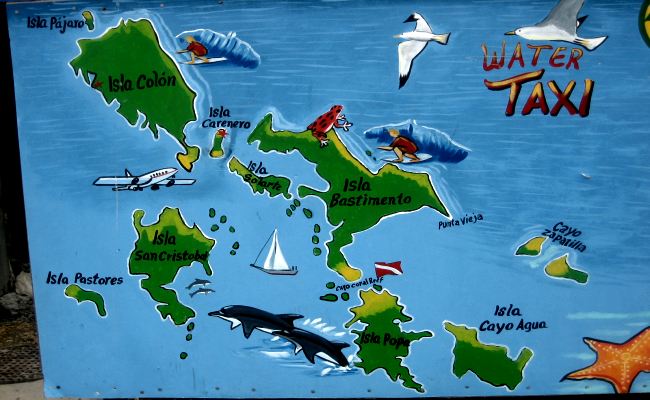

The Bocas del Toro archipelago of six small islands, north of Alouatta and on the Caribbean Sea side of Panama, offer visitors an assortment of activities. Discovered by the Spanish explorer Christopher Columbus in 1502, these islands were the haunt of pirates in the 1600s.

After a fairly smooth 40-minute boat ride from the grimy banana port of Almirante, we landed on the island of Colon. On its southern tip is Bocas del Toro, the biggest town in the area. When we disembarked, the intoxicating odour of diesel fuel and salt water impregnated our nostrils.

Although somewhat scruffy, Bocas del Toro is architecturally quite interesting. Its public buildings tend to be bland and boring, but some of its residential homes, built in the Caribbean style and painted in soft pastel hues, are remarkably beautiful. Bocas del Toro’s palpable Caribbean influence is due to the fact that an influx of Jamaicans were brought here as slaves starting in the early 19th century.

Although vastly outnumbered by people of Spanish and African heritage, Chinese immigrants and their descendants, as well as Palestinian Arabs, own almost all the shops in Bocas del Toro.

Since Colon island is so compact in size, we rented bikes and cycled to all points of interest.

Cycling on a two-lane asphalt road cutting through a pristine rainforest and past banana and teak wood plantations, we stopped at La Gruta, a water-logged cave brimming with slumbering bats and encrusted with guano. As I slogged through the dim cave, which is about 100 metres in length, the water rose progressively higher, until it reached my belly. Not being an adept swimmer, I panicked and almost turned back, but was urged on by my plucky daughter.

We continued on to Boca del Drago, an exceptionally fine beach draped by bent coconut trees and reminiscent of a blissful scene out of the tropics. Under the shade of a tree, I lay down my head on my knapsack and gazed contentedly at the placid water.

With lunch beckoning, we stopped at a modest sea-side cafe. I ordered one of the specials: grilled jackfish, coconut-infused rice, fried plantain and carrot salad, washed down by a local beer. It was delicious.

From Bocas del Toro, we boarded a Class-A ocean-going catamaran for a day of sightseeing, snorkelling and swimming. The captain, a German from Hannover, has lived in Panama for the past two decades.

Clad in cargo shorts and a jersey, I sun bathed under a warm sun and admired the scenery, a tableau of aquamarine waters and distant islands. Most of the other passengers jumped into the crystal clear water with alacrity, swimming into schools of brightly colored fish such as neon gobies and clown wrasses.

Fortified by a simple lunch of a tuna sandwich, beer and a slice of fresh pineapple, we disembarked at a marina where numerous yachts were moored. Walking along a dirt road, we reached Frog beach, where the surf was awesome. I dipped my feet into the foam, but didn’t dare go further.

Boquete, less than 100 kilometres from these idyllic islands, seemed like another world.

Lying about 1,200 metres above sea level, in the temperate highlands of central Chiriqui, a region of coffee plantations, Boquete is located in a fertile valley bisected by the fast-flowing Caldera River.

The town is generally unremarkable, but is blessed with a rustic Spanish colonial plaza, decent cafes and intriguing craft shops where you can buy iridescent butterflies under glass, jewellery, leather belts and souvenirs.

From Boquete, you can go horseback riding and white water rafting in the adjacent countryside. The main attraction, however, is hiking. We signed up for a four-hour hike in a cloud forest, and were driven to the starting point, a trail in a dense rainforest, by jeep.

A gentle rain was falling as we embarked. As we climbed higher into the mountains, we traversed strawberry fields and isolated farmsteads where homes are supported by stilts.

A half hour into the hike, deep in the jungle, we paused at the first of three thundering waterfalls spilling into a rocky gorge. The power of the water was intimidating.

In the distance lay Baru, a dormant volcano that, at 3,475 metres, is the highest point in Panama. Baru, which last erupted 800 years ago, was not our destination, but it tempted the adventurer in me. As we proceeded through the somewhat misty cloud forest, we paused to examine and taste naranjilla, a wild edible fruit that is green and tart, and water cress, a minty, chewy herb.

The rainforest, silent except for the exotic call of birds and the sudden rustle of bushes, was dim and awe-inspiring, a rich melange of mammoth ferns, impenetrable shrubs, delicate flowers of various shades and towering hardwood trees that completely blocked the rays of the sun.

Toward the end of the hike, we stumbled upon baby coffee trees, their white blossoms giving off a heady sweet aroma.

Ah, wilderness!

It had been another bracing day in Panama.