The American Jewish-style delicatessen is struggling for survival. In his elegiac book, Pastrami on Rye: An Overstuffed History of the Jewish Deli (New York University Press), Ted Merwin delves into its rise and falling importance and does so with commendable ease and thoroughness.

As a seasoned aficionado of Jewish culinary traditions, Merwin — a professor of religion and Judaic studies at Dickinson College — seems well positioned to address this topic. “I grew to love eating in delis,” he recalls in the preface. “The fatty, scrumptious food was mouthwatering — the peppery pastrami, the chewy corned beef, the sour seeded rye bread, the fluffy matzoh balls in parsley-flecked chicken broth, the crunchy fresh pickles, the tangy coleslaw.”

This expressive sentence, for me, summons up fond memories of biting into a hot smoked meat sandwich at the Centre Street Deli in Toronto or at Schwartz’s in Montreal, two of the last great delicatessens still standing in Canada.

Merwin’s interest in the deli stems not only from culinary motives. Regarding it as “a place for the reinforcement of American Jewish identity,” he views it as an institution which connected him to “my people and to my past.” Within this framework, he examines the origins and development of the deli from historical and sociological perspectives.

By his reckoning, delicatessen fare originated in New York City and became the mainstay of the American Jewish diet to a degree that was never the case in Eastern Europe, the bedrock of Jewish immigration to the United States from the late 19th century onward.

“Jews ate deli at every stage of their American lives,” he says. “Brises, bar mitzvahs, weddings and shivas — all were marked not just by carefully prescribed religious rites but by the consumption of corned beef, pastrami, rolled beef, tongue and other deli meats …”

And if the kosher deli symbolized ethnic continuity, he adds, the non-kosher deli was emblematic of the movement of Jews into mainstream American society, he claims.

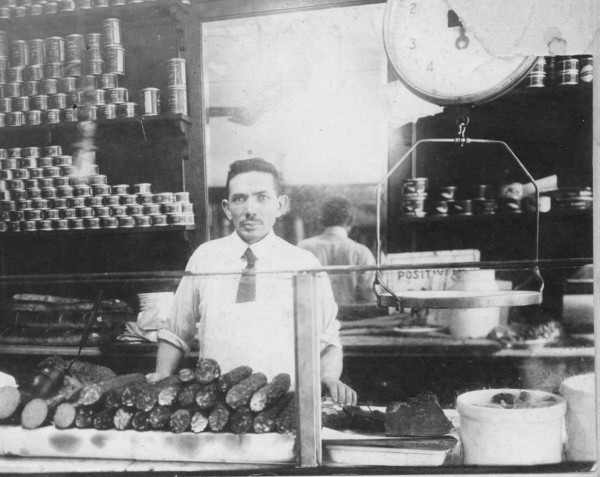

Although smoked and pickled meats were rare delicacies among Eastern European Jews prior to World War II, they were a fixture of the gastronomic landscape in New York City. The first delis, which were often sausage stores, were run by German immigrants, while the first Jewish-owned delis were outgrowths of kosher butcher shops.

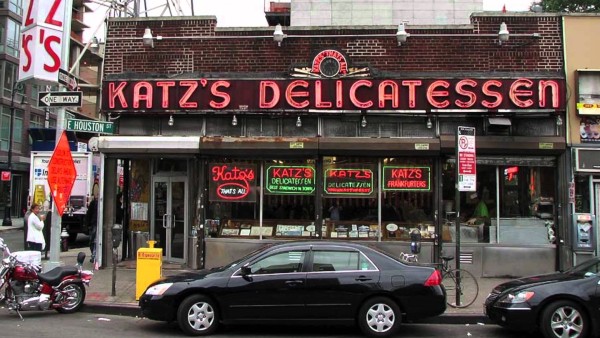

According to Merwin, the first true Jewish deli, Katz’s, opened in 1888 under the name of Iceland’s Delicatessen, and it was soon joined by other delis on the Lower East Side. Delis became targets of a nation-wide campaign to enforce Sunday closing laws. Later, they were subjected to a smear campaign claiming that deli food was unhealthy and unclean.

These accusations had no effect on their popularity. By the 1930s, New York City was home to 2,300 delis, or almost 25 percent of delis in the United States.

Often located near theaters and movie houses, they attracted show business celebrities like Al Jolson and gangsters like Arnold Rothstein, who conducted his illicit affairs at Lindy’s, where he was assassinated in 1928.

Lindy’s was immortalized in short stories by the journalist Damon Runyon and in a Broadway musical, Guys and Dolls, under the moniker of Mindy’s. Runyon, a colorful character, enjoyed its atmosphere. “As I see it,” he wrote, “there are two kinds of people in this world — people who love delis, and people you shouldn’t associate with.”

Presumably, Runyon was able to overlook the often surly waiters who served him at these establishments. “The short-tempered, sarcastic delicatessen waiter was always ready with a cynical remark that cut the customer down to size,” observes Merwin.

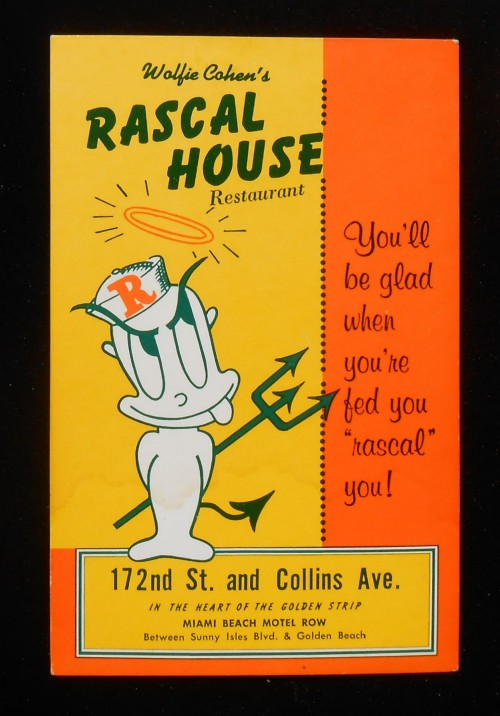

After World War II, New York-style delis proliferated across America. Manny’s Coffee Shop and Deli and Friedman’s Deli in Chicago. Canter’s Delicatessen and Nate n’ Al’s in Los Angeles. Wolfie’s and Rascal House in Miami Beach. (When I was fortunate enough to spend several weeks of winter at my parents’ condo in Sunny Isles, I joined the long queue to get a table at Rascal House).

Several years ago, Rascal House shuttered its doors, like so many delis in the United States. “Beyond the attraction of Jewish New Yorkers to other ethnic cuisines, especially Chinese food, there were a host of other factors that led to the decline of the deli,” explains Merwin.

The Jewish exodus to the suburbs obviated the deli’s role as a neighborhood gathering place, he notes.

Deli owners could neither afford skyrocketing rents in prime commercial districts, nor could they convince their children to take over the business.

The resurgence of Orthodox Judaism spelled trouble for the typical kosher deli. Most modern Orthodox Jews will not eat at a deli unless it is glatt kosher and closes on the sabbath and on Jewish holidays.

As a result of these developments, says Merwin, “the Jewish delicatessen began to seem increasingly like a throwback to an earlier age, its fare hopelessly prosaic, unhealthy and low class.” The kosher deli, in particular, has been relegated to the category of “endangered species.” Only about 15 are left in New York City.

In summing up, Merwin writes, “As Jews moved to the suburbs, they also moved more into the mainstream of American society and ultimately turned their back on delicatessen food in favor of more gourmet, international and healthier fare — even as kosher meat companies sought to increase their market share by selling to non-Jews.”

There is, however, a glimmer of light at the end of the tunnel, he believes. “As long as both Jews and non-Jews want to eat ‘traditional’ Jewish food, delis will always exist in our culture. But they will probably never occupy the centrality in American Jewish life that they once did.”

A pity.