Much to my surprise and delight, Netflix, the international streaming network, has acquired Pawn Sacrifice, a movie I missed at its premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival in 2014.

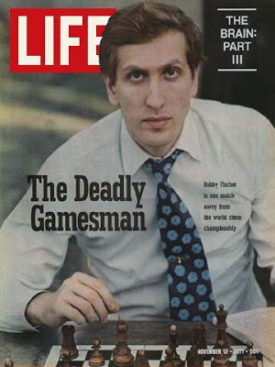

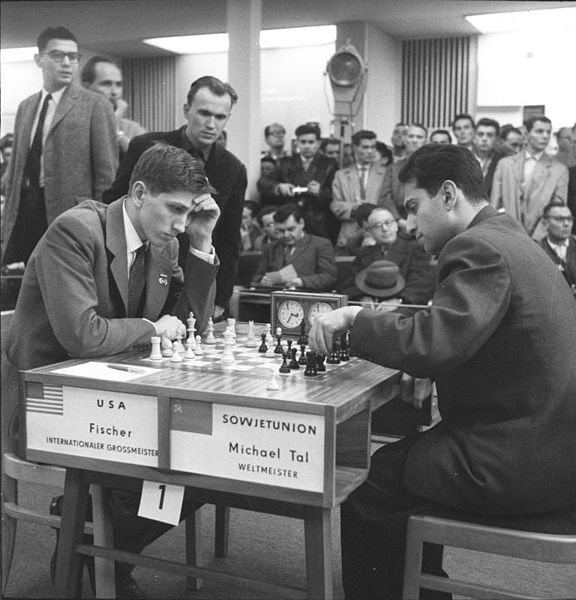

I had looked forward to seeing Edward Zwick’s biopic about American chess prodigy Bobby Fischer, who, in 1972 in Reykjavik, defeated Soviet grandmaster Boris Spassky for the world championship. To my disappointment, the theater filled up quickly and many pass holders like myself were left out in the cold.

When I tuned in to Netflix the other evening, Pawn Sacrifice appeared on the screen. At long last, it was mine to enjoy.

Zwick’s film, starring Tobey Maguire as Fischer and Liev Schreiber as Spassky, is riveting. Which is why I fail to understand why it fared relatively poorly in commercial release in North America and why it was assigned only two-and-three-quarters stars out of five by Netflix.

Be that as it may, Pawn Sacrifice is one of the finest films I’ve had the pleasure of watching. You might not think that a movie about chess — a game I don’t play — could be thrilling and pleasurable. But Pawn Sacrifice is all that and more because it transcends the boundaries of chess, an exacting and complex game.

In sweeping fashion, it takes you from Fischer’s youth in Brooklyn to his triumph over Spassky during the height of the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union. The tournament that pitted Fischer against Spassky went far beyond chess, spilling into the realm of global politics and national prestige.

By no coincidence, Henry Kissinger, President Richard Nixon’s national security advisor, took the trouble of phoning Fischer — a temperamental and mentally unstable person — to convince him to play against Spassky. Being difficult, Fischer had toyed with the notion of pulling out. Rightly so, this episode is included in the movie.

Fischer comes across as an obsessive compulsive figure whose only interest and joy in life derives from chess, to which he devotes himself body and soul. As he rose in the ranks, crushing his rivals in brilliant moves, he became more demanding, self-centered and uncooperative.

His loyal lawyer, Paul Marshall (Michael Stuhlbarg), tried to protect his interests, but sometimes without success. His second, William Lombardy (Peter Sarsgaard), a Catholic priest who had known him since he was a boy, ran into persistent problems with Fischer as well.

Strangely enough, Fischer was an antisemite, a self-hating Jew, and this disturbing dimension of his personality comes through in the final quarter of the film. Zwick makes no attempt to explain this character flaw, but perhaps no explanations are required. Fischer,

as portrayed by Maguire in a sterling performance, was a complicated person, an eccentric at best and a bigot at worst.

The film flows remarkably smoothly, but the most outstanding scenes revolve around Fischer’s confrontation with Spassky, whom Schreiber depicts with aplomb. Palpable tension fills the air as the pair face off against in other and as their respective advisers keep tallies on their progress.

Pawn Sacrifice is a beautifully-crafted and thoughtful movie, but unfortunately, it has yet to find a substantial audience. Its failure to do so is a telling reflection on the state of popular tastes in North America today.