Thanks to a gift from the Archive of Modern Conflict, the Art Gallery of Ontario, in Toronto, possesses the world’s largest collection of photographs from the Lodz ghetto, the last one in German-occupied Poland to be liquidated by the Nazis. Taken by Henryk Ross (1910-1991), one of the few survivors, they offer a rare and depressing glimpse of life inside the second largest Nazi ghetto in Poland.

More than 200 of his gut-wrenching images will be displayed in Memory Unearthed: The Lodz Ghetto Photographs of Henryk Ross, an AGO exhibit which opens on Jan. 31 and closes on June 14. It’s curated by Maia-Mari Sutnik, the AGO’s curator of special photography projects.

“Ross’s images make up a deeply moving record of human life and suffering,” she says. “He had an ability to make many singular moments into poignant narratives, allowing us to reflect on our difficult history …”

The photos, big and small in size and harrowing and heart-rending in spirit, were selected from among 3,000 which have been in the possession of the AGO since 2007.

Ross buried 6,000 negatives in an iron-rimmed box in 1944 as the Nazis accelerated the pace of mass deportations from the ghetto, which had been sealed off in the spring of 1940. “I buried (them) in the ground in order that there should be some record of our tragedy,” he said in 1987, 31 years after he and his wife, Stefania, had immigrated to Israel. “I was anticipating the total destruction of Polish Jewry. I wanted to leave a historical record of our martyrdom.”

During the Holocaust, the Jewish community of Poland, numbering 3.3 million on the eve of World War II, was virtually wiped out by the Nazis and their collaborators. Lodz, a centre of Poland’s textile industry, was a thriving Jewish center, with Jews and ethnic Germans respectively comprising one-third and one-tenth of its population of 672,000.

Germany invaded Poland on Sept. 1939, and a week later, German troops arrived in Lodz, which would shortly be renamed Litzmanstadt, in honor of a World War I German general. On Sept. 13, Adolf Hitler, Germany’s chancellor and supreme leader, visited the city, receiving an ecstatic welcome from local Germans.

Shortly afterward, Joseph Goebbels, the propaganda minister, toured two of its poorest neighborhoods, populated mainly by Jews. He wrote in his diary, “One cannot describe it. They are no longer human beings, but animals.” He added, “One has to cut here, and one must do so in a most radical manner. Or Europe will vanish one day due to the Jewish disease.”

Having established a pseudo rationale for exterminating Jews on a systematic basis, Germany established a ghetto in four square kilometres of Lodz. The Nazi-appointed ghetto elder, Mordechai Chaim Rumkowski, was placed in charge of the factories and workshops that would produce goods and war materiel for Germany in exchange for food and fuel.

Rumkowski, the head of the Jewish Council, promised the Jews of Lodz that if they worked, they would survive. “Our way is work,” he declared. It was an illusory promise. Ideologically committed to the destruction of Polish — and European — Jews, the Nazis began deporting Jewish residents of Lodz to extermination camps in January 1942. The date coincided with the infamous Wannsee conference in Berlin, convened by the Nazi leadership to formalize the extermination of European Jews on an industrial scale.

Tens of thousands of Jews died of hunger and disease long before the deportations got underway. Sanitary conditions in the ghetto were appalling and food was scarce.

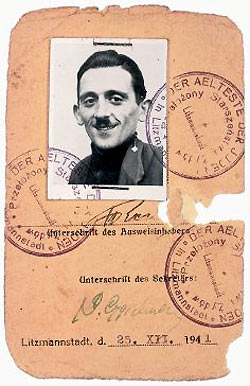

Henryk Ross, who had been a photographer prior to the war, worked for the Jewish Council`s Statistics Department, along with Mendel Grossman and Lejb Maliniak. Ross`s earliest assignment was to take identification photographs for work permits. He used 35 mm cellulose nitrate film. There after, on orders from Rumkowski, who sought to mollify the Nazis, he documented the productivity of the Jewish labor force and idyllic scenes of domestic bliss.

In secret, on pain of execution, he photographed the overcrowding, the dismal living conditions, the despair, the hunger, the empty soup kitchens and the dead and dying.

The final deportations took place in August 1944, when the remaining 65,000 Jews — some from other cities in Europe — were transported to Auschwitz-Birkenau from the Radogoszcz railway station.

Lodz was liberated by the Red Army in January 1945, and two months later, Ross recovered his cache of negatives from beneath the earth. Moisture had destroyed half of them. Still others had been damaged by groundwater. These partially bleached photographs, which are on display at the AGO, are marked by swirls and trails.

Memory Unearthed unfolds in three dim-lit rooms. A fourth room, the smallest, is given over to the heart-felt photographs of Yuri Dojc, a Canadian Slovakian Jewish photographer whose works document traces of Jewish life in pre-war Slovakia: ruined synagogues, crumbling cemeteries, burned books and fragments of sacred texts.

Ross’ photographs, mounted on grey walls, are stark, utilitarian and sometimes almost artless, but they impart the bitter truth he sought to convey and the facile propaganda designed to please the Germans. As I paused to gaze upon them, I was reminded of my parents, David and Genya, survivors of the Lodz ghetto.

The photographs are eclectic.

Jewish Policeman’s Family, an ensemble of four photos, shows a mother, a child and a husband, his face mostly hidden. Conveying mutual love and a trace of angst, it was taken before the mass deportation of children.

Falling on the Street From Hunger portrays two boys, the first lying still on a sidewalk, the second looking away.

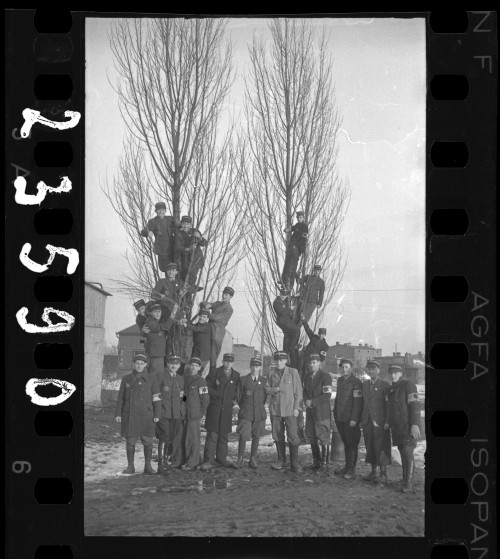

Ghetto Police with Bags of Provisions underscores the relatively privileged status Jewish policemen enjoyed until they were also deported. Men Hauling a Cart imparts a deceptive vision of plenty: a cart piled with fresh loaves of bread.

Additional photographs depict the frantic hunt for food, workers toiling in textile, leather and mattress factories, a nurse tending to four babies in a nursery, the staff of a clinic posing for a picture, a mother cradling a child in her arms, fecal workers hauling away a load of excrement, vendors selling wares, and Jews eating ravenously from pails.

Still other photographs show the pedestrian crossing bridge between the Jewish and non-Jewish parts of Lodz and the ruins of the Wolborska shul, demolished by the Germans in 1939.

Ross’ unofficial photographs, displayed in the third room, are “much more personal,” said Sutnik.

Snapped between 1942 and 1944, they’re of Jews being marched on their final journey to the Radogoszcz train station. One of the photographs, Deportation of Residents (with Sacks and Bedding), is particularly hard to bear.

Photographs are not the only items of interest here. Ross’ identity card, as well as German-issued currency and Judenpost postage stamps, are found in a glass case in the first room.

Near the entrance, Ross and his wife recount their ghetto experiences in a 13-minute video.

Ross’ photographs, simple and unadorned, leave a powerful impression. Seventy five years ago, amidst the carnage of war, Germany — a civilized nation hijacked by a fanatical and nihilistic racist movement — herded the Jews of Lodz into a horribly congested ghetto and inflicted terrible and unimaginable humiliation, pain, deprivation and death upon them. And Ross, the ubiquitous photographer, was there to record this monumental tragedy.

***

An illustrated album about the exhibit, Memory Unearthed, has been published and can be purchased at the AGO.