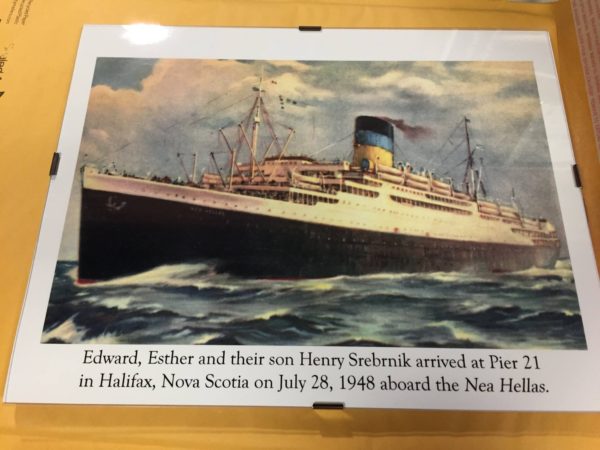

On July 28, 1948, my parents and I arrived at Pier 21 in Halifax as displaced persons following World War II. I had turned three years old during the voyage. We travelled on a Greek ship, the Nea Hellas, which departed from Genoa, Italy, earlier that month.

My parents were Polish Jews whose families had all been murdered by the Nazis. Miraculously, though they spent much of the war in HASAG, a Nazi concentration camp located in their home town, Czestochowa, they both survived the war. I was born six months after the liberation, in the same city.

With no families left in Europe, they left Poland in 1946 and the three of us spent the next two years in a displaced persons camp near Munich, until we were able, thanks to my father’s sister, who had had left for Montreal before the Holocaust, to immigrate to Canada.

And so, like tens of thousands of other refugees, our first sight of this new country was at Pier 21, in Halifax. From there, we travelled by train to our new home in Montreal.

The former ocean liner terminal and immigration shed was the gateway to Canada for some 1.5 million immigrants between 1928 and 1971. As well, it served as the departure point for 500,000 Canadian military personnel during World War II. Some 50,000 war brides and their 22,000 children also passed through Pier 21.

The post-war period was characterized by enormous numbers of immigrants from Germany, Italy and the Netherlands, as well as East Europeans.

An official from Cunard Steamships had declared that “Halifax will have the finest immigration facilities of any port in the world” after reviewing the terminals, and a reporter described his introduction to the new Pier 21 in 1928 as a “tour of revelation.”

For almost 30 years after it closed as an entry for immigrants, the old buildings were used by various other institutions. In 1998, a private community historical group, the Pier 21 Society, obtained a lease for the space from the Halifax Port Authority to construct a museum, using a combination of private and public funds.

It opened on July 1, Canada Day, in 1999. Ruth Goldbloom, president of the Pier 21 Society, called the opening “payment of our greatest national debt to the millions of Canadians who made this great country what it is today.”

In 2011, the operations of the Pier 21 Society were taken over by the newly-created Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21. Today a National Historic Site, it is one of the city’s premier attractions for visitors.

Pier 21 has both a physical artifact collection and a vast oral history collection. It currently holds 2,000 stories, 500 oral history interviews, 700 donated books, 300 films, and thousands of archival images and scans of immigration and other documents.

Many of the resources can be found on its website and all can be accessed by contacting Pier 21’s Scotiabank Family History Centre.

The Pier 21 story collection has broadened from those who actually passed through Pier 21’s doors to include stories about immigration from all points of entry from the early beginnings of Canada (including First Nations) and concentrating on all immigration from 1867 to the present.

Oral historians conduct oral history interviews onsite and occasionally in different centres across Canada.

The image collection includes thousands of scanned newspaper clippings, immigration related documents and ship memorabilia, as well as digital photos donated by individual families and organizations.

I have visited the museum twice, most recently in early August, and walked through the very doors through which my parents and I entered Canada.

I found it a very emotional experience and must admit I choked up both times during the guided tours I was on.

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.