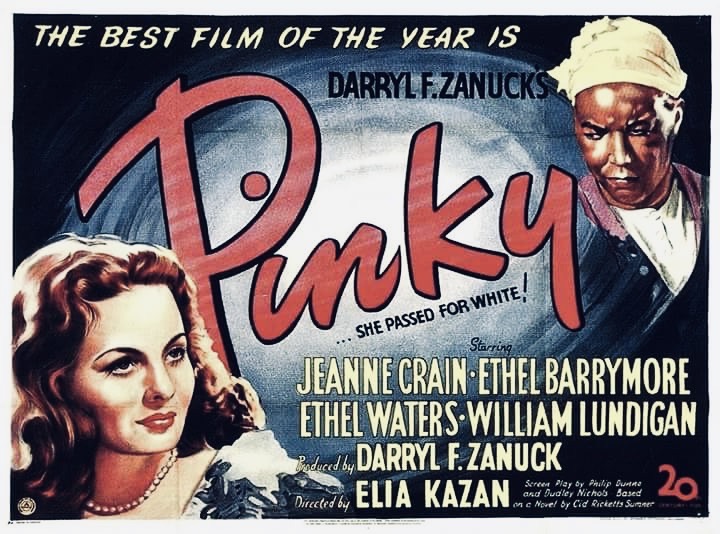

By the standards of the day, Pinky was quite a daring movie. Released in 1949 by 20th Century Fox, it dealt with two related themes: discrimination based on the yardstick of race and racial passing, the phenomenon of fair-skinned African Americans masquerading as whites.

Screened recently on the Turner Classic Movies channel, it revolves around an African America woman, Patricia (Pinky) Johnson (Jeanne Crane), who looks and sounds entirely like a caucasian. After a long absence, she visits her grandmother, Dicey Johnson (Ethel Waters), a washerwoman who is unmistakably black.

Pinky’s racial lineage remains a mystery, since the racial identity of her parents remains a mystery. Yet, for all intents and purposes, Pinky, a nurse by profession, is absolutely white in appearance and tone.

To the white people in Pinky’s small segregated Southern town who have known her since she was a child, she is black. In the South, one drop of black blood is enough to classify a person as as African American.

Produced by Darryl Zanuck, Pinky is directed by Elia Kazan, the director of the 1947 award-winning film Gentleman’s Agreement, which delved into the problem of antisemitism in America. Kazan was hired to direct Pinky after John Ford quit.

Lena Horne, the black actress, was apparently considered for the role as Pinky. But since the Hollywood film industry abided by a code that forbade interracial romances on screen, Crane, an Irish American beauty then at the height of her fame, was chosen.

In Pinky, she resurrects her romantic relationship with Dr. Thomas Adams (William Lundigan), a local white physician in love with her. A rare romance of this kind was strictly prohibited in a country wary of miscegenation and bound by the conventions of segregation.

Crane is anything but an African American in terms of her appearance. As one of the racist characters in the film, Melba Wooley (Evelyn Varden), exclaims, “My goodness, she’s as white as I am!”

Nonetheless, Crane delivered a first-class performance as Pinky, having earned an Academy Award nomination for best actress. Waters and Ethel Barrymore, who portrays a patrician white woman who employs Dicey, received nominations for best supporting actress.

Although Pinky tries to be progressive, its attitude to race is blandly conventional and bound up with the status quo, as its story line demonstrates.

Pinky, slim and radiating confidence, passed as a white while studying nursing in the relatively tolerant north. But whatever illusions Pinky may have had about her racial status are quickly shattered in her hometown. An African American woman denounces Pinky as “a lowdown colored gal,” whereupon she is arrested by the police.

Later, two white men in a pickup truck offer Pinky a lift, wondering what she is doing in the town’s “nigger section.” When she explains she lives there, implying she is black, they try to assault her.

In her capacity as a nurse, Pinky cares for the ailing Miss Em (Ethel Barrymore), who lives in a mansion and has known Pinky since her childhood.

The scene shifts to Pinky’s meeting with Dr. Adams, who expresses surprise that Dicey is her grandmother. The implication is that they met up north, where Pinky could pass as a white. Being a liberal, he insists he is not prejudiced and still loves her.

With the passage of time, Pinky discovers that racial attitudes have not progressed since her departure. Shopping for a blouse in a dry goods store, Pinky is startled when an elderly white woman complains that blacks cannot be served ahead of whites. The store owner, though embarrassed, commiserates with Pinky.

Much to Pinky’s surprise, she inherits Miss Em’s house after her death. Dr. Joseph McGill (Griff Barnett), the executor of her will, warns Pinky that white folks will rise up in protest over Miss Em’s unusual decision to gift property to a black person. Melba Wooley, Miss Em’s bigoted relative, contests the will, sending the case to court. Judge Walker (Basil Ruysdael), Miss Em’s old friend, agrees to be Pinky’s lawyer.

Dr. Adams urges Pinky to back off, assuming that the judge will rule in Wooley’s favor. She rejects his well-meaning advice, but realizes that the court encounter will probably be unpleasant.

Wooley’s hard-driving lawyer accuses Pinky of being a “troublemaker” and opportunist, claiming that Miss Em was of “unsound mind” when he willed her property to Pinky.

The judge delivers a surprising verdict, prompting Judge Walker to pronounce that justice has been done, but that the “interests of the community” have not been served. His lukewarm decision is a reflection of the ambivalency that prevailed among many Americans with respect to race before the emergence of the civil rights movement in the 1960s.

Toward the close of the film, Dr. Adams informs Pinky that he is moving to Denver and asks her to join him there. Her answer disappoints him. She has decided that passing as a white is no longer feasible. Pinky’s path forward unfolds in the final and uplifting scene.

Pinky, a workman-like film and a celluloid relic of the past, hardly questions or challenges American societal assumptions about race. Despite its deficiencies, it accurately reflects reality in the United States as it was seven decades ago.