Few countries were as traumatized by World War II as Poland.

Six million of its 32 million inhabitants, including three million Jews, were killed. The Nazi extermination camps, built to eradicate European Jews, transformed Poland into one big killing field. Poland’s eastern provinces were gobbled up by the Soviet Union, which proceeded to drag it into the totalitarian communist camp.

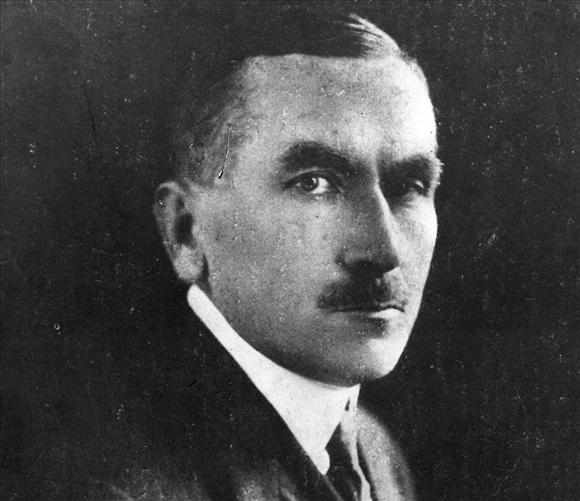

As a result of these seminal demographic upheavals, Poland, which had been a heterogeneous and multicultural nation with significant ethnic and religious minorities, became a homogeneous country, thus fulfilling the dreams of xenophobic Polish nationalists like Roman Dmowski, the leader of the far-right National Democrats party.

The travails and tragedies that Poland endured in six years are thoroughly, but not always fairly, explored in The Eagle Unbowed: Poland and the Poles in the Second World War (Harvard University Press) by Halik Kochanski, a Polish historian.

Sweeping in scope and usually measured in its analysis, this is a fine book, but one colored by spasms of partisanship. Starting with a valuable survey of the period before the rebirth of Poland in 1918, the author delves into the post-war era at length and with gusto.

Poland, having been repeatedly partitioned by the great powers, emerged in truncated form after the 1812 Congress of Vienna. Not exactly an independent state, the new Congress Poland, covering less than 50,000 square miles and with a population of 3.3 million, enjoyed a considerable degree of autonomy, but remained under Russian, Austrian and Prussian control.

Poland fought several wars from 1918 to 1921 to secure its borders — wresting Poznania and Upper Silesia from Germany, Lwow and East Galicia from Ukrainian nationalists, Teschen from the Czechs, Wilno from the Lithuanians and still more territory from Soviet Russia.

Kochanski claims that non-Poles in the new Polish state — 4.4 million Ukrainians, 2.8 million Jews, 989,000 Belorussians and 741,000 Germans, according to the 1931 census — weakened it. “The national minorities had their own religions, which encouraged them to feel separate from strongly Roman Catholic Poland,” she writes.

Compared to the 22 million ethnic Poles, Jews lived mainly in towns and cities and engaged in commerce. Eight out of 10 Jews, she says, were unassimilated and so “looked different” from Poles. Kochanski acknowledges that the stronger Polish nationalism grew, the more the Jewish community turned inward.

Poles, she notes in a broad and somber generalization, viewed Jews as disloyal as the state. Jews in western Poland seemed to be pro-German, at least until 1933, when Adolf Hitler assumed power, and many continued to speak German at home, as if that was a crime. And in the east, Poles recalled bitterly, Jews had fought with the Lithuanians and the Soviets. “This led to the birth of the tragic specter that would haunt Polish-Jewish relations during the Second World War and beyond — zydo-komuna — the communist Jew.”

And in a commentary that seems questionable at best, she adds, “Zionism tended to deter the Jews from loyalty to and involvement in the new Polish state.”

Without mincing her words, Kochanski writes that the National Democrats, a party that dominated Polish politics until Jozef Pilsudski’s coup in 1926, was openly antisemitic and encouraged Jews to emigrate, a policy supported by a broad range of parties.

Poles tend to downplay the existence of antisemitism, but Kochanski does not belong to that school of denial. As she puts it, “Antisemitism became overt and more vociferous during the 1930s as the Depression hit Poland. Economic rivalry between the Poles and the Jews grew as Poles resented Jewish domination of trade and industry and called for a boycott of Jewish shops. The emerging Polish middle class resented the predominance of Jews in the professions and called for the imposition of a numerus clausus to restrict the number of Jews attending Polish universities, some of which notoriously created so-called ‘ghetto benches’ to separate the Jews from the Poles in lecture halls.”

In summarizing Polish-Jewish tensions, Kochanski concludes it was one of the signal failures of the Polish state.

Poland’s quest for security, in a region dominated by Germany and the Soviet Union, is another problem she discusses in detail. As the largest nation in eastern Europe, Poland aspired for great power status, but fell short due to economic and military deficiencies. This was extremely unfortunate for Poland, since it was mostly surrounded by enemies. Notably, Germany bridled at the Polish corridor, which separated East Prussia from the rest of the country, while Lithuania was outraged by the Polish seizure of Wilno.

To protect itself, Poland signed a defensive alliance with France in 1921 and entered into a non-aggression pacts with the Soviet Union and Germany in 1932 and 1934 respectively.

As Kochanski suggests, Poland was difficult to defend because it possessed relatively few natural barriers: the Pripet marshes in the east and the Carpathian mountains in the south, to name two. No such barriers existed between Poland and Germany, to Poland’s misfortune.

On paper, the Polish army, with one million soldiers and another million in the reserves, appeared strong. But Poland was short of heavy tanks and combat airplanes.

- German soldiers in Poland after Germany’s invasion in 1939

When Germany invaded Poland on Sept. 1, 1939, the Poles were essentially alone. Poland’s allies, France and Britain, declared war on Germany but did not have the will to fight alongside Poland.

Poland’s casualties in the fighting were frightful: 66,300 soldiers and pilots killed, with another 133,700 wounded. German losses were far lower: 10,572 killed, 30,322 wounded and 3,409 missing.

To add to its misery, the Red Army occupied eastern Poland.

The German occupation zone comprised 72,800 square miles of territory inhabited by 20 million Poles. The Soviet zone of 77,720 square miles was populated by 12 million Poles.

After failing to find suitable Polish collaborators, the Germans cracked down hard, particularly on the Jewish population, limiting Poles and Jews to respectively 938 and 369 calories a day by the end of 1940.

Two hundred and fifty thousand Jews fled into the Soviet zone in a desperate effort to save themselves from Nazi brutality. The remainder were subjected to terror on an unprecedented scale.

Like Ukrainians, Belorussians and Lithuanians, Jews welcomed the arrival of Soviet forces in eastern Poland. “The presence of a large number of Jews in the welcoming crowds shocked the Poles and contributed towards strengthening the existing antisemitic beliefs that some held,” Kochanski writes.

She understands why Jews reacted positively to the Soviet occupation. The Soviets would protect them from the Germans.

In this vein, Kochanski speculates that the massacre in the northeastern town of Jedwabne, in which anywhere from 300 to 1,000 Jews were murdered by Poles, may have been touched off by vengeance for “the perceived prominence of the Jews in the Soviet administration.” More likely, old fashioned antisemitism was the cause of the pogrom.

Similarly, she downplays the Polish reaction to the Nazi mass murder of Polish Jews. “The Jews, the Poles, the world outside, could not comprehend the logic of (Germany’s) policy, and their disbelief and consequent inaction made the job of the Germans easier.”

This argument is disengenuous. Most Poles were acutely aware of Nazi objectives during the Holocaust, but preferred to remain neutral and silent.

As she later admits, the Polish underground government and resistance movement “reacted too slowly to the tragedy unfolding in Poland, and resources were put in place to rescue Jews only after the major deportations had taken place …”

Kochanski charges that the allies betrayed Poland, its interests having been sacrificed by Winston Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt to appease Joseph Stalin. At the Tehran conference in 1943, she observes, Britain and the United States ceded eastern Poland to the Soviet Union, thereby undermining the authority of the Polish government-in-exile in London.

In summing up, Kochanski reminds a reader that World War II left Poland devastated. Apart from the catastrophic death toll, Polish cities were left in ruins, while 60 percent of Poland’s industrial capacity was destroyed. Poland’s cultural and intellectual elite was virtually wiped out, and much to the anguish of nearly all Poles, Poland was converted into a Soviet satellite state, like Hungary, Bulgaria, East Germany and Czechoslovakia.

Kochanski does not hesitate to call a spade a spade with respect to the wave of antisemitism that washed over Poland from late 1944 onward: “There were numerous instances of antisemitism among the Polish population directed towards the (Jewish) survivors, which stemmed from a number of factors.”

Citing one of them, she refers to the disproportionate number of Jews who held leadership positions in the Soviet-backed communist regime. This renewed the specter of zydo-komuna. In this connection, Kochanski says, it`s still unclear whether the murder of 500 to 1,500 Jews in Poland from November 1944 to the middle of 1947 was rooted in antisemitism or in rage against their communist sympathies.

Claiming that the historiography of Polish-Jewish relations during World War II was subjected to “political manipulation” by the communist authorities, she cites Zegota, a Polish organizations that helped Jews during the Holocaust. The communist regime, however, downplayed Zegota’s role due to its ties to the Polish-government-in-exile.

In conclusion, Kochanski says that the demise of communism enabled Poland to look westward again and be true to its national essence. By joining the NATO alliance and gaining membership in the European Union, Poland was not only set free, at last, but allowed to write “the final chapter” of World War II.