This year marks the 50th anniversary of the outbreak of the state-orchestrated “anti-Zionist” campaign in Poland, then under Communist rule. At the time, Jews numbered no more than 30,000 members out of a Polish population of 32 million.

Cold War politics and a power struggle within the Polish Communist party would result in a purge that would force at least 20,000 Jews, themselves ironically mostly Communists, to leave the country.

Organized by the Polish United Workers’ Party (PZPR), the CP’s official name, the anti-Zionist campaign virtually destroyed a Jewish community which had only just reestablished itself after the Holocaust. It was a classical example of left-wing antisemitism.

The backdrop to the massive exodus was Israel’s victory over its Arab enemies in the Six Day War of June 1967. The defeated countries included Soviet-backed Egypt and Syria, and in response, the member states of the Warsaw Pact, with the exception of Romania, cut diplomatic ties with Israel on June 9.

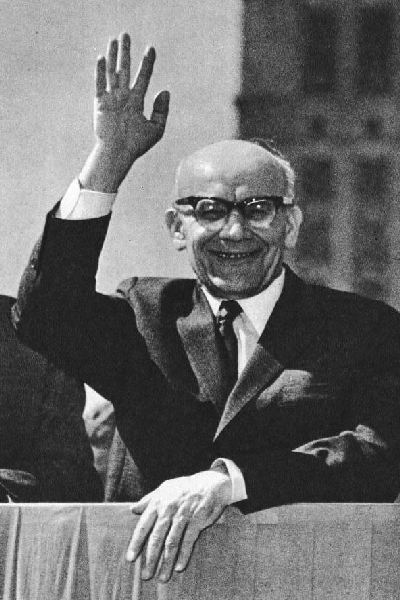

On June 19, Wladysław Gomułka, the first secretary of the PZPR, accused some Polish Jews of sympathizing with the enemies of socialism, thus forfeiting their claim to be loyal Polish citizens. “Israel’s aggression in the Arab countries was met with applause in Zionist circles of Jews — Polish citizens,” he declared.

A well-organized international Zionist conspiracy, whose center was to be found in the Jewish community, was trying to undermine the Polish socialist state. These people constituted a fifth column in the country, which had to be eradicated before it could gain strength. He compared them to the German minority living in Poland that supported the Nazi invasion in 1939.

When Gomułka gave his speech, he was already in a power struggle with the Ministry of Internal Affairs, under the command of General Mieczyslaw Moczar, a fervent antisemite. (It did not escape his notice that Gomulka’s wife was Jewish.)

Though the subsequent purges of Jews within the ruling party, led by Moczar and his faction, known as the “Partisans,” failed to topple Gomułka’s government, it resulted in an expulsion from Poland of thousands of individuals of Jewish ancestry, including major figures in the military and state offices.

It all started with a seemingly unrelated event. On January 30, 1968, some 300 University of Warsaw students protested the decision to ban further performances of the allegedly anti-Russian play Dziady by the 19th century author Adam Mickiewicz. Though it was written in 1824 and set in tsarist times, Polish authorities viewed the play as targeted against the Soviet Union.

The protest leaders, known as the Komandosi (Commandos), included Adam Michnik and Jan Litynski, both Jews, and the students then gathered around the Mickiewicz monument in the center of Warsaw demanding a cessation of censorship.

Michnik and another Jewish student, Henryk Szlajfer, then met with a journalist for the French newspaper Le Monde. They informed him about the situation amongst the Warsaw intelligentsia. Their statements were later used by Radio Free Europe, and they were expelled from the university.

In response, about one thousand students gathered on the campus on March 8 demanding their reinstatement. This rally began the mass student protests throughout the country known as the “March events.”

The protests were brutally suppressed and the student groups were called “enemies of People’s Poland.” The antisemitic campaign, which had begun in 1967, was now stepped up. A March 11 article in the newspaper of the Catholic splinter group PAX, Słowo Powszechne, made the link between the student opposition and the “Zionist fifth column.”

Within the next ten days, 250 articles were published, a good portion of which endorsed the anti-Zionist conspiracy theory. In more than 100,000 public meetings throughout Poland, anti-Zionist resolutions were passed. As the attacks on the Jewish community intensified, some Communists produced documents confirming that they were baptized as proof they did not have a Jewish background!

“Polish citizens who are emotionally and in their thoughts connected to the State of Israel” would have to leave the country, Gomulka announced in a speech on March 10, as he emphasized the Jewish origin of the instigators.

“Loyalty to socialist Poland and imperialist Israel is not possible simultaneously,” Prime Minister Jozef Cyrankiewicz declared on April 11. “Whoever wants to face these consequences in the form of emigration will not encounter any obstacle.”

Entire academic departments were dissolved, and thousands of members of the country’s intelligentsia, including outstanding scientists, artists and academics such as Zygmunt Bauman were driven out of the country.

Almost 9,000 Jews lost their jobs and hundreds were thrown out of their apartments. Of the 8,300 members expelled from the PZPR, nearly all were Jewish.

The regime allowed Jewish citizens to leave the country under two conditions: they must revoke their citizenship; and they must declare Israel as the country of their destination. The victims of the 1968 campaign were made stateless upon leaving Poland while their possessions were confiscated by the Polish state.

Since few of these Jews were actually Zionists of even the mildest variety, fewer than 30 percent of them ended up in Israel, with the rest going to other countries, including Norway, Sweden, France and the United States.

In June 1968, the Central Committee decided to discontinue the campaign. By the Fifth Party Congress in November, Zionism was no longer on the agenda.

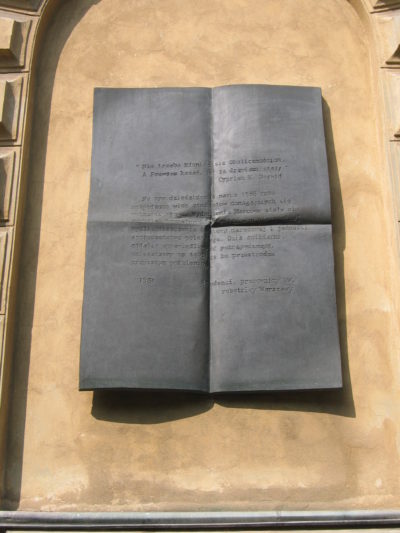

One memorial to the expulsions is a small plaque on the wall of the Warszawa Gdanska railway station on the north side of the city, off Highway 637.

It was from there that many Poles of Jewish origin departed. It bears a tribute from the Polish-Jewish writer Henryk Grynberg: “For those who emigrated from Poland after March 1968 with a one-way ticket. They left behind more than they had possessed.”

Visitors to Warsaw can also see a commemorative plaque at the university for the students demanding freedom of speech in 1968 on the wall of one of the buildings surrounding the courtyard. The university entrance is on Krakowskie Przedmiescie (the Royal Avenue) in Warsaw’s Stare Miasto (Old Town).

There has been much renewed controversy in recent months regarding Poland’s complex history involving the treatment of its Jewish population, particularly during the Holocaust.

This was triggered by a bill passed this month that seems to prohibit any claims that Poland participated in the mass murder of its own Jews.

According to the new law, “anyone who, in public and contrary to the facts, imputes that the Polish Nation or the Polish State was responsible or co-responsible for the Nazi crimes committed by the Third Reich or for other crimes against peace, humanity or war crimes, or otherwise grossly diminishes the responsibility of the actual perpetrators of these crimes, shall be liable to a fine or imprisonment of up to 3 years.”

For the ruling right-wing populist Law and Justice Party (PiS), the initial motive was meant to prevent the use of the term “Polish death camps” to refer to those centers set up by the Nazis in occupied Poland.

But it goes further, as it also will fine or jail people who blame Poland or Poles for Nazi atrocities committed on Polish soil during the war, in effect outlawing accusations of Polish participation in the Holocaust.

While we Jews can and should take offence at some of the remarks that have been made, most of this — though badly explained by Polish authorities — relates to anger on Poland’s part that the country is being lumped in with actual World War II pro-Nazi collaborationist regimes, such as those in France, Hungary, Slovakia, Croatia and Romania.

There was no Polish government at all during the war (except in exile in London), and Poland was itself ground zero for the murder of some six million Polish citizens (Jews and non-Jews), apart from the millions of others from across Europe killed in the Nazi death camps located in the country.

The Nazi occupiers intended to destroy Poland as a nation, to Germanize a large chunk of the country and to turn the rest of it into a German agricultural colony.

Of course this does not mean that Poland itself was not an antisemitic country at various times in its history, as was evident 50 years ago during the anti-Zionist campaign.

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.