Sebastian Rejak, Poland’s envoy to the Jewish Diaspora, has spent the past two-and-a-half years assiduously cultivating relations with Jewish communities throughout Europe and North America to improve his country’s ties with the Diaspora.

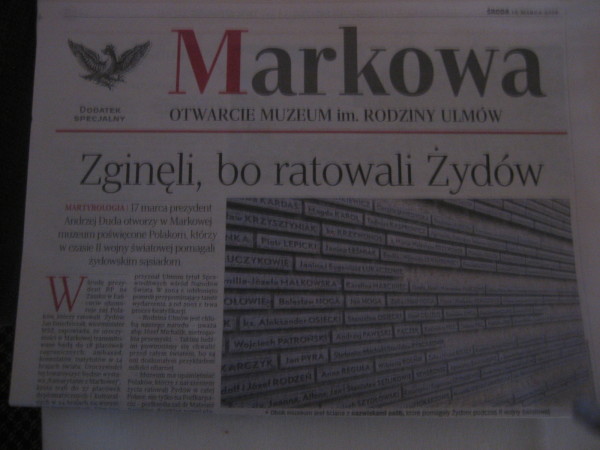

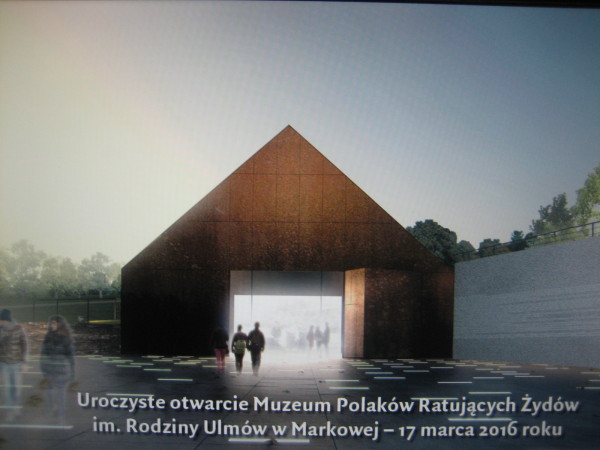

Most recently, he worked behind the scenes to stir awareness of the new Ulma Family Museum of Poles Saving Jews in World War II, which was officially opened in the Polish village of Markowa on March 17 in the presence of Poland’s president, the chief rabbi of Poland, a contingent of Polish bishops and one archbishop and foreign diplomats.

The event was meticulously covered by Polish media, and live streaming from it was presented by Poland’s missions in 17 countries ranging from Israel and Canada to Germany and the United States.

As Rejak acknowledged in an interview in Warsaw on March 16, it was a big deal for Poland, a chance to buff up its image in the eyes of Jews and the international community.

The museum, eight years in the making, honors Polish rescuers of Jews, but focuses on Jozef and Wiktoria Ulma, a middle-aged couple from Markowa. In 1942, as the Nazi hunt for Jews intensified, eight Jews asked the Ulmas for help, and they agreed to shelter them. In exchange, the Jews worked on their farm.

On March 24, 1944, German police, acting on a tip from a Polish informer, fatally shot the Ulmas, along with their six children and the Jews in their care. The Ulmas had committed the unpardonable crime of hiding Jews. In 1941, the German governor of occupied Poland, Hans Frank, had issued an order forbidding Poles to assist Jews on pain of death.

Yad Vashem, the Holocaust research and educational center in Jerusalem, recognized the Ulmas as righteous gentiles in 1995. About a decade later, the Vatican launched a beatification process to confer sainthood on the Ulma family.

As Rejak suggested, Poland tapped into the Ulmas’ heroism to offset a public relations disaster caused by the publication of Jan Tomasz Gross’ book, Neighbors, in 2001.

A Polish American historian who had left Poland in 1969, Gross examined the 1941 pogrom in the northeastern town of Jedwabne, during which a mob of antisemitic Poles, encouraged by the Germans, burned down a barn with at least several hundred Jews crammed inside.

Neighbors sparked an impassioned debate in Poland because it tarnished the cherished notion that Poles had been victims of Nazi aggression. Now, in Neighbors, they emerged in a far different light, as hateful oppressors of Jews.

To Jews in the Diaspora, Jedwabne seemed to confirm their worst suspicions about Poles. Antisemitism had been a malevolent phenomenon in pre-war Poland. A cadre of Polish collaborators and blackmailers had tormented Jews during the Holocaust. A pogrom had erupted in Kielce in 1946. More than 10,000 Jews had been driven out of Poland in the wake of the 1968 antisemitic campaign, which had been dressed up as an anti-Zionist response to so-called Israeli warmongering in the 1967 Six Day War.

Markowa, however, presented the Polish government with an opportunity to adjust negative Jewish perceptions of Poland, where 3.3 million Jews lived on the eve of the war.

Rejak agreed that the events in Markowa may work in Poland’s favor.

“We want to balance the picture more,” he said in reference to the pogrom in Jedwabne. “But I hope the museum won’t be used to claim there were only good Poles. History is too complicated to paint a country in only one color. There are many colors in history. But there is a general feeling among Poles that Poland has been perceived through the prism of pre-war antisemitism and wartime blackmailers who betrayed Jews. This image has, in general, dominated discourse about Poland.”

Nevertheless, Poland is obliged to “own up” to its past, he said. “It’s a complex history. We have to take into account the extremes.”

In his view, the new museum, financed by Markowa and the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage, will serve as a positive role model for Polish youth.

The younger generation, he noted, appreciates the richness of Jewish culture and regards it as an integral component of Polish history. “It’s inextricably a part of what we are as Poles,” he said. “But to my regret, there is still a degree of antisemitism in Poland.”

Rejak admitted that the Roman Catholic church has not always played a positive role in fostering good Polish-Jewish relations, but he pointed out that John Paul II, the late Polish-born pope, succeeded in diminishing antisemitism in Poland.

Nonetheless, there are priests who have not accepted his ecumenical teachings. “In the church, change comes slowly,” he said.

Asked how many Jews live in Poland today, Rejak said that 7,353 Polish citizens had declared themselves Jewish in the 2011 national census. “The actual number may be several times greater,” he added. “There is a core Jewish population and a non-practising segment of Poles of Jewish descent.”

Rejak expressed the hope that the Jewish community, a pale imitation of its former self, will continue to grow and thrive, and that Polish society at large will be “receptive” to a “Jewish presence in Poland.”

Now 42, Rejak comes from a traditional Catholic family in Lublin, where he studied Judaism and Jewish history. He joined the foreign service in 2006 and has held his current job since November 2013.

He does not deal directly with issues pertaining to Israel. “There is a special desk officer at the Foreign Ministry for Israel,” he said.

The position he holds was created in 1995, six years after Poland made the transition from communism to democracy and around the time the Polish government applied for membership in the European Union and NATO, the Western military alliance.

The timing was hardly coincidental, but Poland places great value on its Jewish dimension, said Rejak, who did not meet a Jewish person until the late 1990s.

Possessing a working knowledge of Hebrew, he’s the author of two books. The first, Jewish Identities in Poland and America: The Impact of the Shoah on Religion and Ethnicity (Vallentine Mitchell, 2011), is a spinoff of his PhD dissertation. The second, Inferno of Choices: Poles and the Holocaust, was published by RYTM in 2012.

A member of the Polish Society for Jewish Studies, Rejak cannot conceive of a situation in which Poland would be bereft of Jews. As he put it, “It’s impossible for me to imagine Poland without Jews. It would be a tremendous loss for Poland.”