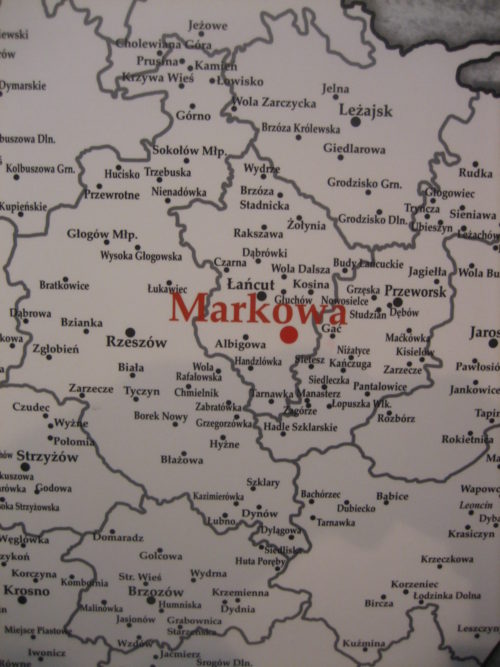

An obscure village in a remote corner of southeast Poland, the kind you can drive through in seconds, was in the spotlight recently. On March 17, an array of personalities descended on Markowa, in Poland’s Podkarpacie district, for the official opening of The Ulma Family Museum of Poles Saving Jews in World War II.

The ceremony, covered in minute detail by the Polish media and broadcast abroad in 11 languages, was attended by Poland’s newly-elected president, Andrzej Duda, who heaped praise on Poles who helped Jews during the Nazi occupation; Michael Schudrich, the chief rabbi of Poland, who affixed a mezzuza on the museum’s door, and a contingent of Polish bishops and foreign diplomats, including the Israeli ambassador to Poland, Anna Azari.

As might have been expected, the event elicited local interest. Hundreds of townspeople gathered in an open field to watch the ceremony on a big screen outside the enclosed VIP area, where more than 1,000 people sat.

The multi-media museum, built at a cost of $2.9 million (Canadian) and financed by Markowa and the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage, honors the approximately 1,500 Poles who rendered assistance to 2,900 Jews in the region.

It pays special attention to Jozef and Wiktoria Ulma, a middle-aged couple who sheltered eight Jews on their farm. When a Polish policeman informed the Germans of their whereabouts in March 1944, the Ulmas were doomed. The Germans immediately killed them, their six children and all eight Jews under their protection.

Their heroism has earned them the posthumous designation of Righteous Among the Nations, a title conferred on Christian rescuers by Yad Vashem, the Holocaust research and education memorial in Jerusalem. As well, a beatification process now underway at the Vatican may well result in sainthood for the Ulmas.

The Ulmas knew they had jeopardized their lives by hiding Jews. In 1941, the German governor of occupied Poland, Hans Frank, issued a directive warning Poles that they would face the death penalty if caught aiding Jews. On the eve Germany’s invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939, Poland was home to 3.3 million Jews. Only the United States had a bigger Jewish population.

For Poland, the inauguration of the museum was a shining moment in its problematic relationship with Jews, an opportunity to alter negative perceptions about Poles.

Fifteen years ago, the Polish American historian Jan Tomasz Gross wrote Neighbors, a book that caused a sensation and then an impassioned debate in Poland. He left Poland in 1969, following a state-sponsored antisemitic campaign that had demonized and marginalized Polish Jews.

The focus of Neighbors was a pogrom in the northeastern town of Jedwabne, during which a mob of antisemitic Poles, egged on by the Germans, herded at least several hundred Jews into a barn and set it alight in a frenzy of xenophobia and hatred.

This shameful incident, reflected in the 2012 Polish movie Aftermath, shattered the carefully cultivated notion of Polish victimhood. With three million Poles having been killed during the course of the war, Poles regarded themselves as victims of Nazi aggression. But with the publication of Neighbors, Poles were suddenly thrust into the unsavoury role of perpetrators, a status that did not sit well with right-wing Polish nationalists.

The controversy was reignited this past winter when the Polish government, controlled by the right-wing Law and Justice Party, announced its intention to strip Gross of the Order of Merit he had been awarded in 1996 for his books on Poland. The announcement prompted University of Ottawa historian Jan Grabowski to compliment Gross as a scholar who “looks at both the darker and lighter periods in Polish history.”

To me, the idea of Poles as oppressors was not exactly new.

As the son of Polish Jewish Holocaust survivors, I came to learn that Polish Jews had generally little good to say about their Polish Christian compatriots. My late father, David, and my mother, Genya, had experienced the sting of antisemitism in prewar Poland and had never forgotten or forgiven the Poles, who, they claimed, were antisemites to the marrow of their bones.

During the 1930s, antisemitism reached stomach-turning heights in Poland, a nation where Christians and Jews had coexisted in relative harmony since the Middle Ages. With the advent of Polish independence in 1918, after decades of Prussian, Russian and Austro-Hungarian imperial domination, hostility against Jews grew by leaps and bounds.

The National Democratic Party, a major bloc in parliament, called for an economic boycott against Jewish-owned businesses, and the Roman Catholic church supported it. Jewish university students were subjected to harassment. The government of the day encouraged Jews to emigrate.

Germany’s invasion of Poland spelled utter disaster for its Jewish citizens. Physical abuse gave way to ghettoization and mass murder as Jews were deported to extermination camps such as Treblinka, Sobibor and Auschwitz-Birkenau.

During the war, more than 90 percent of Polish Jewry was murdered. According to Feliks Tych, the editor of Memory: The History of Polish Jews Before, During and After the Holocaust, the overwhelming majority of Poles were bystanders as the Nazi’s Final Solution unfolded with brutal efficiency. In short, self-preservation was the name of the game. “Most Poles considered the Holocaust as an event that in fact did not concern them,” he writes.

Sebastian Rejak, Poland’s envoy to the Jewish Diaspora, concurs with this assessment: “The vast majority of Poles were indifferent or inactive. You can’t expect most people to be heroes. This is normal.”

Still other Poles collaborated with the Germans, impelled by antisemitic motives or driven by considerations of financial gain.

A tiny minority of Poles, however, acted decently and courageously, saving some 50,000 Jews. One example, in particular, comes to mind. Irena Gut, a Polish nurse, hid 12 Jews in the villa of a German army commander for whom she worked as a housekeeper. A network of 26 Poles saved Barbara Gora and her family. Hidden in a succession of homes in Warsaw and the countryside, they were liberated by the Red Army when it entered the city.

In Warsaw, Rejak told me that less than one percent of Poles lent a helpful hand to Jews. “They were doing a heroic job,” he said. By Tych’s estimation, upwards of 200,000 Poles were involved in rescue efforts. Some were guided exclusively by altruistic motives. Others demanded money for expenses incurred. Still others were only interested in potential profits.

The fact remains that more than 6,000 Poles have been designated as “righteous gentiles” by Yad Vashem, a number that far exceeds any other country occupied and plundered by the Nazis.

Almost 1,000 Poles were killed by the Nazis for assisting Jews, said Marcin Urynowicz, a historian employed by the Warsaw-based Institute of National Remembrance, which designed the exhibit inside The Ulma Family Museum of Poles Saving Jews in World War II.

When the war broke out, Markowa, about 300 kilometres from Warsaw, was inhabited by 4,300 Christians and 120 Jews. The Jewish residents were mainly tradesmen, buying farm produce and animals from peasants and running shops.

The Jews and Poles of Markowa mingled, but lived apart, constituting two solitudes, says historian Mateusz Szpytma in The Risk of Survival, published under the auspices of the Institute of National Remembrance.

Like the other residents of Markowa, the Ulmas witnessed the roundups and executions of Jews during the summer of 1942, when Operation Reinhard, the Nazi campaign to exterminate the Jews of Poland, was in full swing. As the hunt for Jews intensified, a group of desperate Jews, like Shaul Goldman and Lea Didner, approached the Ulmas for help, and they agreed to shelter them.

On March 24, 1944, German military police and Polish collaborators appeared at the Ulmas’ farmstead, having been tipped off by Wlodzimierz Les, a member of the collaborationist Blue Police. The Ulmas were summarily executed, along with their children — Stasia, Basia, Wladzio, Franus, Antos and Marysia — and the Jews in hiding. Ulma’s wife was seven months pregnant when she was murdered.

The simple museum in Markowa, featuring photographs, prints and documents, not only pays homage to their humanity and bravery, but honors the estimated 1,500 Poles in the district who risked their lives and that of their families to help Jews.

Roman Romaniuk, the vice-marshall of the Podkarpackie region, voiced the hope that the museum will inspire future generations. “We need positive role models,” he said.

“We can’t ever do enough to pay tribute to righteous gentiles like the Ulmas,” said Rabbi Schudrich. “Thanks to them and like-minded Poles, Europe was able to rebuild itself on a spiritual and moral level.”

Certainly, the exemplary behaviour of the Ulmas stands in sharp contrast to the manner in which the Poles of Jedwabne conducted themselves in relation to their Jewish neighbors.

Rejak acknowledged that the Polish government is using the wartime events in Markowa to accentuate the positive and polish its international image.

“We want to balance the picture more,” he said in reference to the pogrom in Jedwabne. “But I hope the museum won’t be used to claim there were were only good Poles. History is too complicated to paint a country in only one color. There are many colors in history. But there is a general feeling among Poles that Poland has been perceived through the prism of pre-war antisemitism and wartime blackmailers who betrayed Jews. This image has dominated discourse about Poland in general terms.”

The new museum in Markowa, he suggested, may well be helpful in highlighting the humanitarian contributions of Poles in the rescue of Jews and in the realignment of Poland’s image in the world.

A shorter version of this article was published in The National Post on April 18, 2016.