Poland was a charnel house during World War II, a place of death for Jews and Christians alike. Three million Christians and an equal number of Jews perished during Nazi Germany’s inhumane occupation of Poland.

Amid the darkness, a small minority of decent, courageous Polish Christians risked their lives to help Jews, a crime punishable by death during the war. More than 600 Poles have been recognized so far as righteous Christians by Yad Vashem, the Holocaust research and education center in Jerusalem.

Recently, in Poland, I met the daughter of the late Irene Gut Opdyke, a Polish nurse who single-handedly rescued 12 Jews, and Barbara (Basha) Gora, a Polish Jewish woman who owes her life to 26 Polish Christians.

Gut Opdyke died in 2003, but her 58-year-old daughter, Jeannie (Janina) Smith, has been telling her story to audiences around the United States for years. “One person can make a difference,” said Smith, who delivers up to 300 speeches a year. “It’s a message of hope, faith, courage and doing good.”

“It’s also about the power of love,” she added.

A resident of Woodland, Washington, Smith was in Poland in mid-March to attend the opening of the Ulma Family Museum of Poles Saving Jews in World War II in the village of Markowa. I caught up with her in the nearby city of Rzeszow, in southeastern Poland. This was her first visit to Poland.

Gut Opdyke is a legendary figure. Her autobiography, In My Hands: Memoirs of a Holocaust Rescuer, published in 1999 by Alfred A. Knopf, was turned into a Broadway play, In My Hands, starring Tovah Feldshuh.

About two months ago, Smith signed a contract with a Hollywood studio to turn In My Hands into a feature film. A script is currently being written.

Smith, who describes herself as a philosemite, spoke effusively about her mother, who was born in Kozienice in 1922. Blonde and blue-eyed, she was of partial German ancestry.

She joined the Polish underground following the German and Russian invasions of Poland in 1939. Raped by a Red Army soldier, she was treated in a Soviet hospital. After escaping, she witnessed one atrocity after another in various parts of Poland.

“She saw things no one should see,” said Smith. “A death march of Jews wearing Star of David armbands. A German soldier grabbing a baby from her mother, throwing it into the air and shooting it. Watching Germans killing Jewish civilians and burying them in pits.”

As she told these stories, Smith, a tall, graceful person, grew even more emotional.

“My mother raised her eyes to heaven and asked God why this was happening. God gives us the free will to be good or bad. She promised to help.”

Following a stint in a German arms factory in Tarnapol, now in Ukraine, Gut Opdyke found employment in a German army camp in the same city. The German commander, Eduard Rugemer, gave her a job in the mess hall and laundry, where 12 Jews worked as forced laborers.

Having overheard they would soon be deported, she broke the bad news to them. They pleaded to be hidden, but she was powerless to render assistance. Shortly afterward, by chance, Rugemer hired her to be his housekeeper. He lived in a villa the German army had requisitioned from its Jewish owner.

She offered the Jews a safe haven in Rugemer’s basement. By day, when he was away, they helped Gut Opdyke clean the house and cook the meals. “They lived that way for the next two years,” said Smith.

Rugemer was enraged when he discovered her secret, but pledged to abide by the status quo if she agreed to be his mistress. In the meantime, she helped a pregnant Jewish woman under her protection to give birth to a son, Roman Holler.

In the wake of the Soviet conquest of eastern Poland in 1945, Gut Opdyke was accused of being a German spy and imprisoned. One of the Jews whom she had saved smuggled her out of jail. Gut Opdyke ended up in a displaced persons camp in Germany. In 1949, she immigrated to the United States, where she found a job in New York City’s garment district.

Gut Opdyke married a Dutch official whom she had met in Germany. They moved to California, where she became an interior decorator. By then, she had learned that her father, an architect, had been killed during the war. Around this time, she was reunited with her four sisters, with whom she had lost touch.

In 1972, she received a crank call from a Holocaust denier, an incident that prompted her to become a speaker on the Holocaust. “Her philosophy was pretty straightforward: We’re all part of the human family and should love each other,” said Smith.

Ten years later, Roman Holler called Gut Opdyke. He told her an incredible story. Rugemer’s wife, having found out about his affair with Gut Opdyke in wartime Poland, kicked him out of the house. Finding himself homeless, he was “adopted” by Holler’s parents.

Smith, a grandmother, says her mother disliked being described as a hero. “She was a flawed human being of flesh and blood, but she made choices that made a real difference.”

***

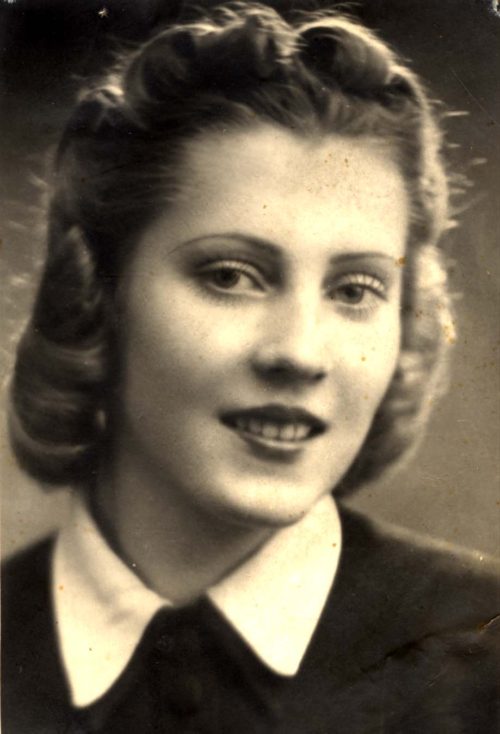

Barbara Gora lives in Warsaw, a spry single woman of 83 whose memories are razor sharp.

Shortly after the first massive deportation of Jews from the Warsaw ghetto in the summer of 1942, Gora’s resourceful father, an electrician, smuggled her into the Christian sector of the city.

“I had ‘good looks’,” she said. “I didn’t look Jewish.”

She and members of her family were separately hidden by a network of Poles, among whom was an ethnic German whose husband was a Jew. “She was a very brave woman,” recalled Gora.

During the doomed 1943 Warsaw Ghetto uprising, she lived with a family in a village near Warsaw. It was the only time her father was required to pay for a safe haven.

Neither Gora nor her parents had any desire to leave Poland after the war. “It’s our country,” said Gora, who graduated from university as an agronomist and joined the Communist Party. “I always felt Polish.”

Nor was she interested in emigrating after the Communist government launched an antisemitic campaign in 1968 under the guise of anti-Zionism. “It was a terrible period,” she said, adding that her boss saved her job by denying he had Jewish employees.

Gora left the Communist Party in the early 1980s, but still considers herself a leftist.

For years now, she has told her story of survival to students in Poland and Germany. “I don’t hate Germans,” she said. “It’s important to educate the new generation in democratic values.”