Opposition has arisen to a sensible proposal by American businessman/philanthropist Sigmund Rolat to build a memorial in Warsaw to honor Polish Christians who risked their lives to rescue Jews during the Holocaust.

Rolat, a Holocaust survivor from Poland, hopes it can be built in Warsaw’s former Nazi ghetto, next to the new Museum of the History of Polish Jews and near a monument honoring the Jewish fighters of the Warsaw ghetto uprising.

According to reports, Rolat’s plan is supported by Poland’s chief rabbi, Michael Schudrich.

Claiming his idea is flawed, Rolat’s detractors contend that the former ghetto area should be reserved exclusively for Jewish mourning and should not be a site for Polish self-aggrandizement. They also advance the argument that a memorial in this particular place would be jarring, conveying the patently false impression that the majority of Christian Poles helped Jews in their hour of need.

This is no minor debate. The issues go to the heart of Polish-Jewish relations in the first half of the 20th century.

During the German occupation of Poland — a nation rife with antisemitism after its national resurrection in 1918 — the vast majority of Christian Poles passively accepted the Nazi marginalization and persecution of Polish Jews. In short, they regarded this national tragedy with shocking indifference. Many Christian Poles perceived Jews as aliens and worse. For some Poles, only a Catholic could be a genuine Pole.

My father, who was born and raised in the Polish city of Lodz, remembers ugly confrontations with local antisemites who rarely lost an opportunity to curse him or send him on his way to Palestine. Despite these insults, he took up arms for Poland, fighting as a soldier in the Polish army after Germany’s invasion on September 1, 1939. Wounded in battle, he was treated in a German clinic before being sent back to Lodz.

Antisemitism in Poland was something the German occupiers exploited to the hilt in their ceaseless propaganda campaigns. The Germans also issued a draconian decree imposing the death penalty on Christian Polish rescuers and their families. Understandably enough, this edict deterred countless Christian Poles from lending a helping hand to Jews in distress.

Nonetheless, thousands of decent and humane Poles risked life and limb to assist Jews during the darkest times. Yad Vashem, the Holocaust center in Jerusalem, has honored more than 6,500 Poles as Righteous Gentiles.

The historian Gunnar Paulsson estimates that 100,000 Christian Poles were directly involved in the rescue effort, while another 200,000 to 300,000 offered some form of help. Wladyslaw Bartoszewski, the late Polish foreign minister who was friendly to Jews, estimated that one to three percent of the Polish population participated actively in the rescue of Jews.

Some Christian Poles, of course, were guided by monetary considerations. Still others acted on purely humanitarian grounds. Irena Sendler, a member of Zegota — the Council for Aid to Jews — was one such honorable Pole. She was instrumental in smuggling about 2,500 Jewish children out of the Warsaw ghetto before its destruction in 1943.

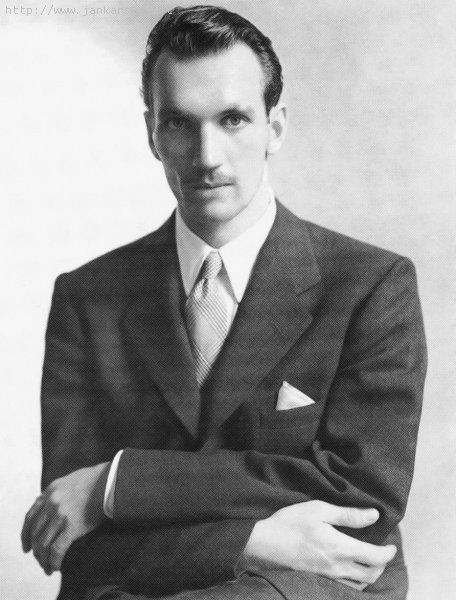

And lest we forget, Jan Karski, an emissary for the Polish government-in-exile, informed the British and U.S. governments of ongoing Nazi atrocities against Jews in his homeland.

By one estimate, the rescue of a single Jew required the cooperative efforts of a dozen or more people, all of whom risked their lives in defying the Germans. Two examples will suffice. The pianist Wladyslaw Szpillman, whose rescue was commemorated in a moving feature film directed by Jerzy Polanski, was helped by 30 Christian Poles. Hanna Krall, the journalist, was assisted by 45.

In their zeal to exterminate Polish Jewry, the Nazis offered rewards and inducements to Christian Poles to turn in Jews in hiding. Some gladly cooperated with the Germans. The Polish Canadian historian Jan Grabowski, among others, has written about this dimension of the Holocaust in a first-class work, Hunt for the Jews: Betrayal and Murder in German-Occupied Poland.

While it is sadly true that most Christian Poles exhibited either indifference or hostility to Polish Jews during the Holocaust, it should never be forgotten that a courageous minority did the right thing under the worst of circumstances.

Their humanitarianism deserves recognition in the form of a memorial in the heart of Warsaw, as Rolat has wisely suggested. The former ghetto area should not only be a place for mourning the dead, the three million Polish Jews who perished during the Holocaust. It should also be a place to mourn the living — the Jewish survivors who owe their lives to Christian rescuers.