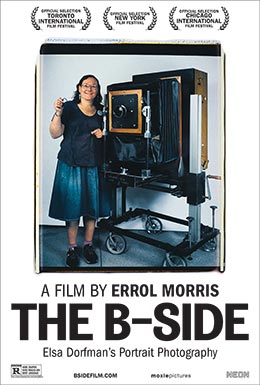

Elsa Dorfman, an American portrait photographer whose subjects run the gamut from Allen Ginsberg to W.H. Auden, was once under-appreciated. Today, she’s sufficiently important enough in photographic circles to rate rave reviews from peers and clients alike. Certainly, filmmaker Errol Morris thinks highly of her, judging by his biopic, The B-Side, which opens in Canada on June 23.

Dorfman’s claim to fame was her role in pioneering the potential of large-format 20 x 24 Polaroid color photographs. She adapted to the clunky large camera with apparent confidence and ease and never looked back.

Polaroid went out of business eight years ago, clobbered by the digital camera revolution, but Dorfman, now 80 and retired, retains fond memories of what was a cutting-edge instrument in its day. “I owe my life to Polaroid,” she says gushingly at one point in the film.

In Morris’ plain and unadorned documentary, which was shot in her studio and darkroom in Cambridge, Mass., she looks back at a life of accomplishment without ever sounding conceited or boastful. A cheerful person, she’s voluble and rarely at a loss for words.

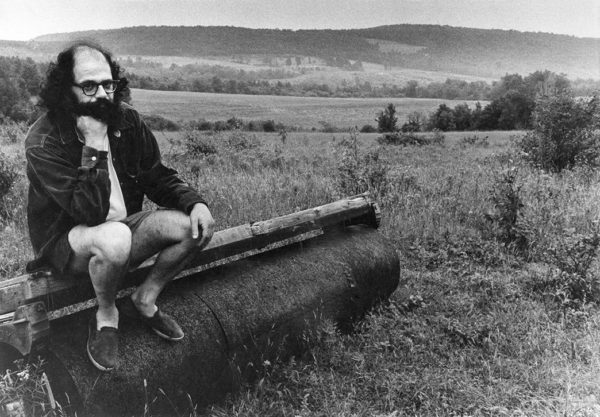

After graduating from university, she landed a job as a secretary with Grove Press, an avant-garde publisher in New York City. She didn’t stay long, but managed to acquire a high-powered coterie of acquaintances and friends in literary circles who consented to be photographed by her. In one of Dorfman’s photographs, the poet Ginsberg appears stark naked. She claims it was his idea to pose in the nude.

After leaving the Grove Press, Dorfman segued into elementary school teaching. During this phase, she discovered photography. “I was just one lucky Jewish girl,” she says.

Not exactly.

As she readily admits, she had to struggle to gain recognition. In her early years as a photographer, Dorfman sold her pictures on the street for only $2 each. “My work was so rejected and put down,” she says.

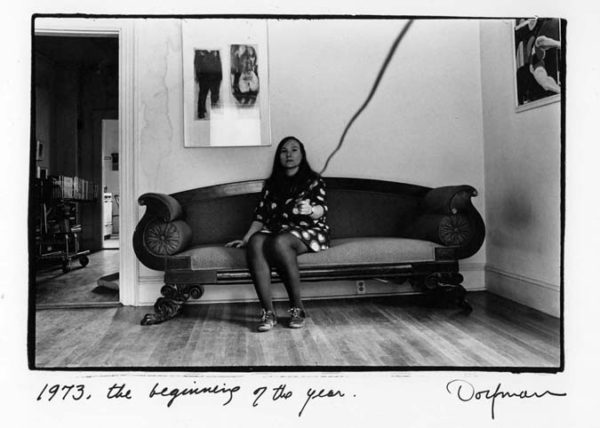

Dorfman’s portraits are direct, uncomplicated and down-to-earth, an approximation of her personality. In explaining her style, she says she aims to capture the “surfaces” of her subjects. She is not interested in “capturing their souls.” She doesn’t tell clients how to pose and what expressions to assume. Her raison d’être is to make them feel better about themselves. “My work is about affection,” she observes.

Dorfman has no illusions about her calling. “The camera doesn’t tell the truth,” she claims, adding that a set of photographs can be quite different in terms of composition and mood.

The title of the movie is a reference to photographs clients have rejected but which she has kept in her files. She doesn’t consider them inanimate objects and says she loves them as much as her own family.