Canadian historian Paul Brykczynski has written an authoritative account of a long-forgotten incident in Poland’s early 20th century history that altered its political landscape and undermined its large Jewish community.

The “December Events,” as he describes them, unfolded in 1922 against the backdrop of a closely-fought election, anti-Jewish street riots and the assassination of a president. Until now, historians have usually glossed over these incidents, but Brykezynski treats them with the importance and gravity they deserve.

As he writes in Primed for Violence: Murder, Antisemitism and Democratic Politics in Interwar Poland (The University of Wisconsin Press), a valuable contribution to Polish historiography, “This story is about nationalism and the struggle … for the ‘soul of the Polish nation.’ It is a story about the role of antisemitism in Polish history and politics, and the challenges faced by those who sought to resist it. It is also the story about the rise of the radical right and the breakdown of democracy …”

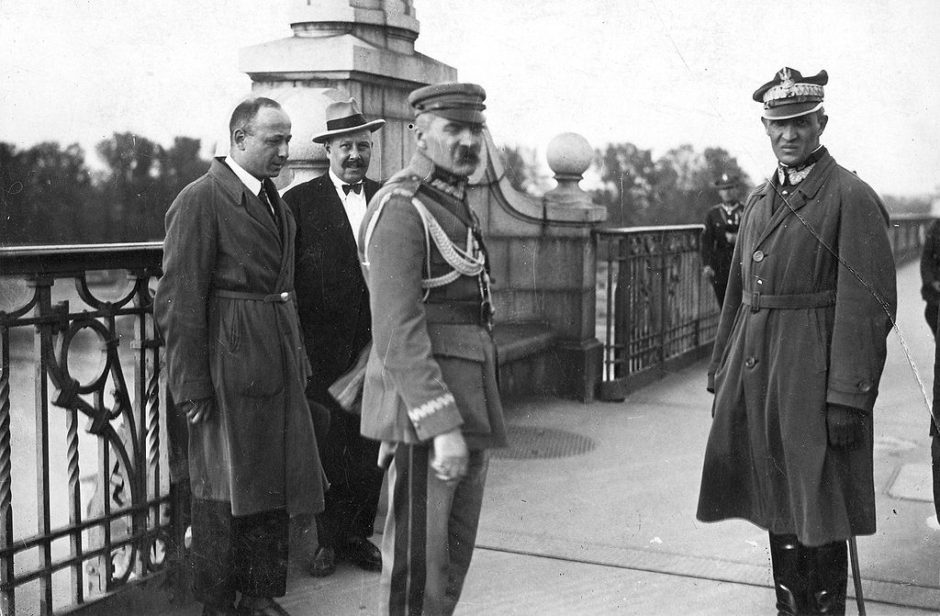

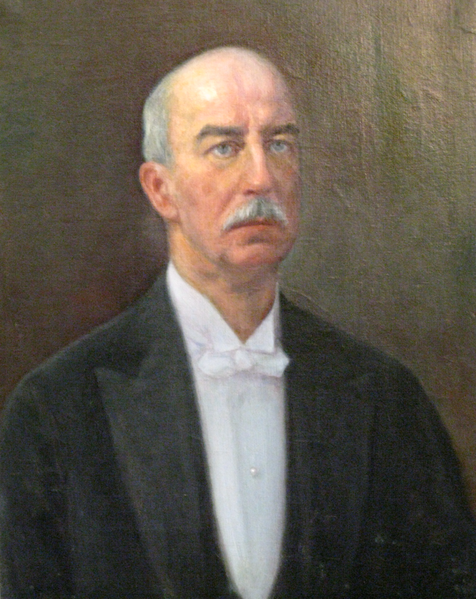

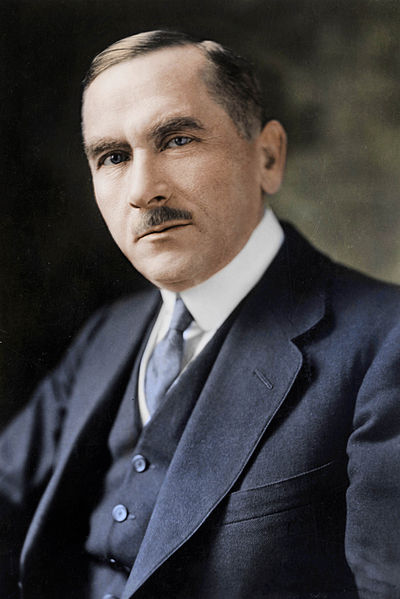

On December 9, 1922, about four years after Poland regained its sovereignty after more than a century of foreign domination, Gabriel Narutowicz — a moderately liberal, Swiss-educated civil engineer — was elected Poland’s first president by the National Assembly. A friend of Marshal Jozef Pilsudski, the towering figure who governed Poland after it secured its independence, Narutowicz owed his election to the backing he received from the National Minorities’ Bloc, a loose coalition of Jewish, Ukrainian, Belarusian and German parties.

Narutowicz’s victory enraged the right-wing nationalist camp, known as the National Democrats (Endeks or NDs). Violent antisemitic riots broke out in Warsaw, forcing the government to declare martial law. On December 16, a week after his electoral triumph, Narutowicz was assassinated by Eligiusz Niewiadomski, a prominent painter who sought to save Poland from what he perceived as Jewish domination. Eight days later, the National Minorities’ Bloc threw its support behind Narutowicz’s successor, Stanislaw Wojciechowski, but this time calm prevailed.

The chaos that briefly engulfed Poland nearly a century ago precipitated a national debate in the media concerning the definition of “Polishness” and the place of Jews in the state. It was the most explicit and sustained debate of its kind since the resurrection of Polish statehood in 1918. This heated discussion prompted the National Democrats to formulate the Doctrine of the Polish Majority, which held that only “ethnic Poles” had the right to rule Poland. For a while at least, politicians and intellectuals on the left challenged that racist doctrine by emphasizing citizenship and culture over ethnicity.

These duelling narratives should be seen within the context of the historic struggle between civic and ethnic nationalism in Poland, writes Brykczynski, whose book is based on newspaper articles, memoirs, electoral pamphlets, parliamentary minutes and police reports.

The national movement emerged in Poland in the 19th century, when it was partitioned between Russia, Prussia and Austria. As Brykezynski suggests, this movement was demonstrably civic and inspired by the defunct Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, which had rejected notions of race or ethnicity. This multinational concept was dismissed by the godfather of the National Democrats, Roman Dmowski, who popularized the idea of ethnic Polish nationalism. Initially, he regarded Germans as the Poles’ chief enemy, but by the end of World War I he had turned his animus toward Jews, propagating the myth that an international Jewish conspiracy was intent on destroying the Polish nation.

Pilsudski, on the other hand, looked back to the multicultural Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, which embodied a strain of nationalism that was more inclusive and liberal. His supporters in the Patriotic Left movement, which he headed, included socialists, radicals, liberals, peasants and minorities.

As Brykczynski points out, antisemitic nationalism was already a potent force when Poland was reborn in the wake of World War I, “more powerful than some Polish historians like to admit.” But Narutowicz — the descendant of a noble family in Lithuania who had served as foreign minister before his elevation to the presidency — shared Pilsudski’s civic vision of the Polish community. Pilsudski, a former socialist, promoted this view after his seizure of power in 1926.

According to Brykczynski, Narutowicz’s election marked an attempt by Poland’s minorities to play a leading and constructive role in Polish politics, much to the anger of the National Democrats, who controlled some 40 percent of the seats in the National Assembly. Twenty five percent of its seats were held by left-wing parties, including the Polish Socialist Party and the radical peasant Emancipation Party. The leftists enjoyed the support of the centrist Peasant Party (Piast) and the National Minorities’ Bloc, 40 percent of whose seats were occupied by Jews.

It was widely assumed that Pilsuski, a national hero and unifying force in Polish politics, would run for the presidency. When he withdrew from the race, the National Democrats announced they could not accept anyone who had been chosen by “the Jews.” Their candidate, Count Maurice Zamoyski, was defeated by Narutowicz, a technocrat, following five rounds of voting. Narutowicz offered Zamoyski the position of foreign minister, but he declined.

In response to Narutowicz’s election, Antoni Sadzewicz — a National Democrat deputy and the editor of one of its publications, Gazeta Poranna — framed the election as a Jewish attempt to subvert the will of the Polish nation. Taking its cue from him, the right-wing press claimed that the outcome of the election had been illegitimate. Gazeta Warszawska, another mouthpiece of the National Democrats, claimed that Narutowicz owed his career to “Jewish financial circles.”

Pro-National Democrat protesters took to the streets, marching down Warsaw’s two biggest thoroughfares, Marszalkowska Street and Jerozolimskie Avenue, and beating up people, especially those who looked Jewish. In the meantime, the National Democrats — an alliance of the National Populist Union, the Christian National Party and the Christian Democratic Party — announced they would boycott Narutowicz’s swearing-in ceremony, thereby putting further pressure on him to resign.

Amid the turmoil, the leader of the Piast Party, Wincenty Witos, had a profound change of heart. He embraced the Doctrine of the Polish Majority and urged Narutowicz to step down.

Strangely enough, Dmowski, the ideologue who had been instrumental in injecting antisemitism into Polish politics, remained silent during the tumult. Brykezynski attributes his inaction to health problems and an inability to share power with rivals. (In 1923, however, he was briefly foreign minister).

He contends that political antisemitism was a relatively new phenomenon in Poland when Narutowicz was struck down while attending an art exhibition. Popular prejudice against Jews had not been uncommon in the 19th century, particularly among peasants and the nobility, but the Polish national movement was supportive of Jewish emancipation and civic rights. “The picture began to change in the 1880s with the emergence of the National Democratic Party, which eventually made hatred of Jews its central political plank,” he says.

By the 1920s, he adds, the National Democrats blamed Jews for everything that was wrong in Poland and saw themselves as the only authentic representatives of “Polishness.”

The core of Pilsudski’s followers rejected antisemitism as unethical and morally base. Until his death in 1935, Pilsudski resisted ever-increasing calls by the far right to implement antisemitic legislation. But two years after his passing, Marshal Edward Rydz-Smigly, one of his disciples and Poland’s de facto ruler, openly endorsed political antisemitism.

In closing, Brykczynski claims that the December Events should be viewed as a victory for the National Democrats. As he puts it, “The formulation of the Doctrine of the Polish Majority provided the proponents of antisemitism with a new focus and lent their credo a new coherence.”

Narutowicz’s murder, he goes on to say, convinced many Polish politicians that it was “more expedient to appease the antisemites than to challenge them.” Centrist politicians like Witos and Wladyslaw Sikorski were, in principle, opposed to political antisemitism. “But they clearly decided that defending the political rights of the Jews and other minorities was not a battle worth fighting.”

The adoption of political antisemitism by much of Poland’s political class was the culmination of “a long and complicated process,” notes. But there can be little doubt that the election and assassination of Narutowicz hastened the drift toward this deplorable state of affairs in Poland.