Marianna Barr’s intriguing Israeli documentary, Private Death, fleshes out a forbidden romance set against the backdrop of rising tensions between Jews and Arabs in 1930s Palestine. It will be screened online at the Toronto Jewish Film Festival, which runs from June 3-13.

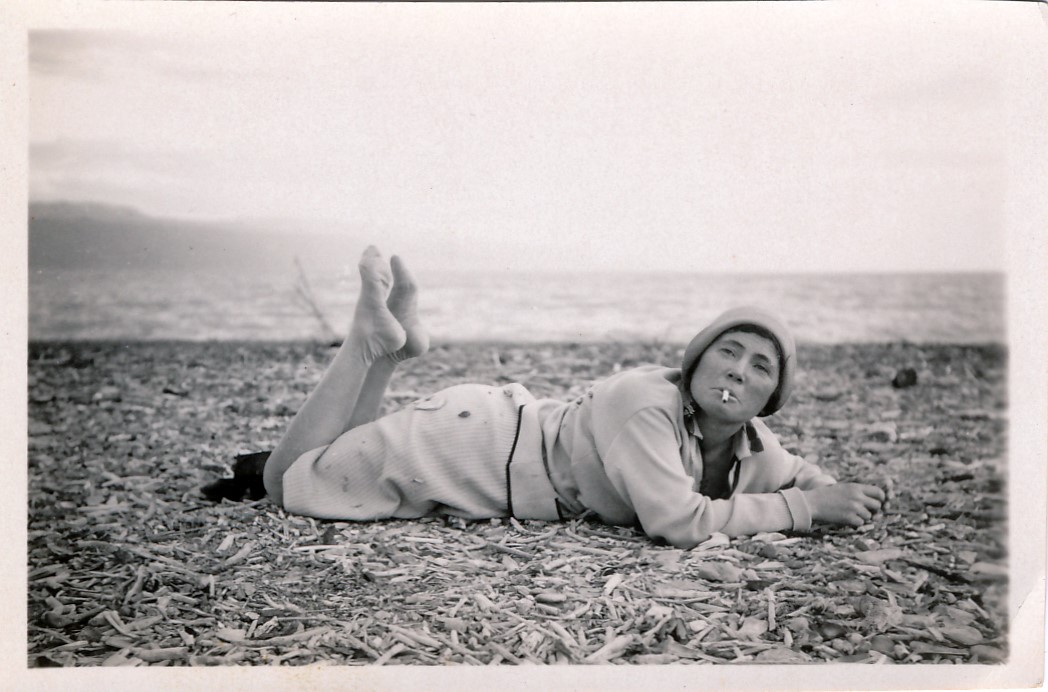

Haya Schreiber, a sixth-generation Jaffa-born Jew from an ultra-Orthodox family, and Tewfik Hanania, a Greek Orthodox Palestinian Arab from Jerusalem, were the unlikeliest of lovers. As the film suggests, their very unusual love affair was possible because they were unconventional people who moved in circles where ethnicity and religion did not necessarily define the wholeness of a person.

Their relationship in Private Death is described through vintage photographs and reminiscences by Haya’s Israeli relatives. Hanania’s side of the family goes completely unmentioned, as if they are ciphers.

Haya, a kindergarten teacher, met Hanania, a businessman, through Pinchas Litvinovsky, a painter and mutual friend. From that point onward, nothing could tear them apart. But such was the climate of their times that they were unable to get married while they lived in Jerusalem.

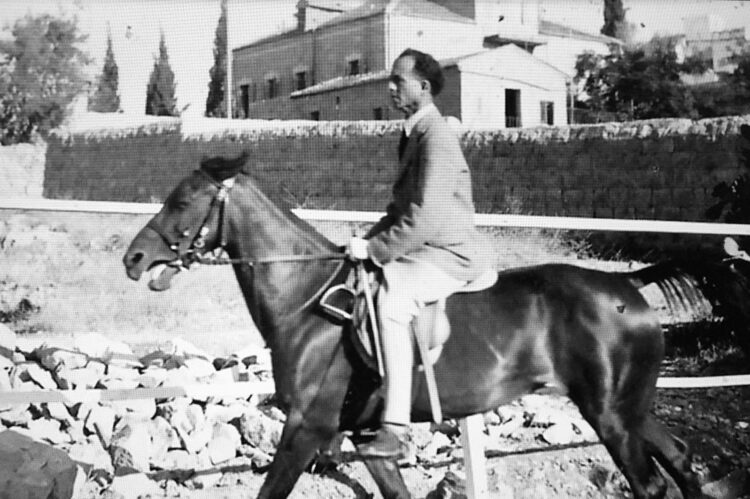

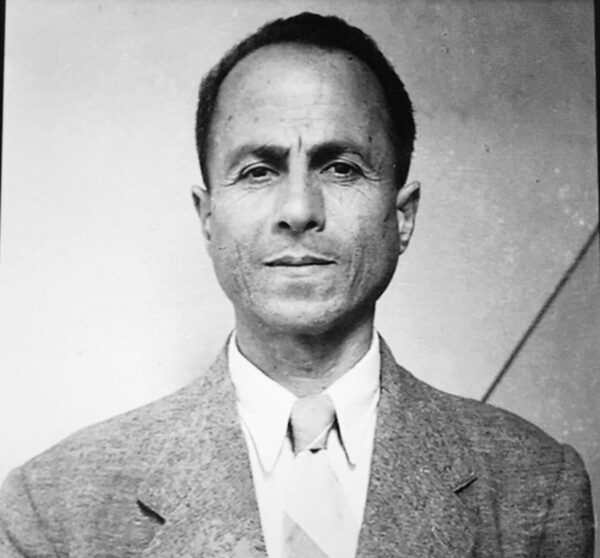

Hanania was a unique Arab in Mandate-era Palestine in that he was close to Jews. He knew the Schreiber family so well that he seemed like an integral part of it. Unfortunately, Barr does not explain how he became so enmeshed in their lives.

Described as an “aristocratic” Christian whose ancestors settled in Jerusalem in the 18th century, he made his fortune in the photography business and parlayed his windfall into real estate investments in Jerusalem and Haifa.

Regarded as a bohemian, despite his neat demeanor and pedantic style, he spoke Arabic and French, the languages in which he and Haya conversed.

Midway through the film, Barr goes off on something of a tangent by delving into the conflict that pitted the Zionist movement against Palestinian nationalism. She returns to the topic at hand by noting that Haya was temporarily stuck in Jerusalem’s Old City when the 1948 war broke out.

Most Palestinians voluntarily left their homes and property as the fighting intensified, and Hanania’s friends urged him to flee as well. Hunkering down in Cyprus for the duration of the war, during which more than 500 Palestinian villages were abandoned, he corresponded with Haya.

The new state of Israel did not allow Palestinian refugees to go back to their homes and expropriated their lands, much to their eternal bitterness. Hanania’s Jewish lawyer convinced the authorities to return his properties because of services he had rendered during the war. He allowed the Haganah fighting force to use his spacious house in the rolling hills of southern Jerusalem as an observatory point.

It’s unclear why Hanania threw in his lot with Jews, or what he thought of the Palestinian national movement. An explanation would have been useful.

With new immigrants from around the world streaming into post-war Jerusalem, Hanania felt like a foreigner in the fast-changing city. In an attempt to blend into his new surroundings, he tried to learn Hebrew at an ulpan, but his effort were in vain.

Feeling uncomfortable and alienated in Israel, he joined his sister in Clearwater, Florida, hoping he would soon be reunited with Haya. She visited him in 1960 after a five-year absence. Returning some years later, she decided to stay with him in the United States.

What happened next is the stuff of fantasy and tragedy, a story of star-crossed lovers who could not bear to be separated.