Ben Ferencz, a chief prosecutor at the Nuremberg war crimes tribunal, played a critical role in the establishment of the International Criminal Court. Now 98 and living in retirement in Delray Beach, Florida, he was instrumental in crafting the legal process by which war criminals are prosecuted.

To Rosalie Abella, a justice on the Supreme Court of Canada, he is nothing less than an “iconic figure” in this increasingly important field of law.

Barry Avrich’s probing documentary, Prosecuting Evil: The Extraordinary World of Ben Ferencz, examines his career and contributions. It opens in Canada on November 30.

Ferencz thinks war can make a murderer out of an otherwise decent person. Yet remarkably enough, he’s something of an idealist, believing we’re currently in the process of creating a more humane world. When he was a young man, he explains, there was no such thing as “human rights” and the word “genocide” had yet to be coined.

But at the end of the day, he has no illusions about the depths to which mankind can sink. Ferencz inspected German concentration camps shortly after their liberation and he prosecuted the commanders of the Einsatzgruppen, the Nazi mobile killing squads which murdered about one million Jews in the Baltic states and the former Soviet Union. So he’s very much familiar with the mentality of mass murderers.

Avrich, a Toronto-based filmmaker, paints a positive portrait of his subject, who’s as mentally alert in his late 90s as he was decades ago.

Ferencz and his parents left Romania in 1920, the year he was born. He grew up in Hell’s Kitchen, a rough-and-tumble neighborhood of New York City largely inhabited by Irish and Italian Americans. Since his mother tongue was Yiddish, he was not admitted to a public school until he had learned English satisfactorily. It seems odd that Ferencz, a precocious boy, had not acquired fluency in English when he was old enough to start school.

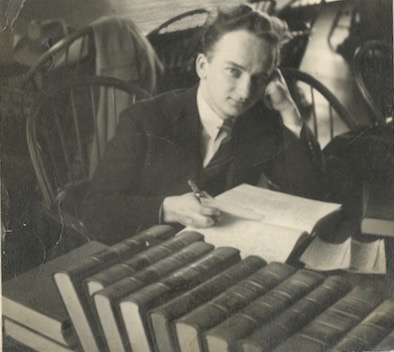

An aspiring lawyer, he studied at City College, which he describes as the “poor man’s Harvard.” Sailing into Harvard Law School on a scholarship, he specialized in criminology.

Having graduated, he joined the army. Appointed a war crimes investigator, he was sent on inspection tours of concentration camps in Germany. His son, Don, says he was shocked by the horrific sights. As Ferencz delves into the details, he chokes up momentarily.

After the war, he was eager to return to New York, but the U.S. government offered him a new post in occupied Germany. “My life took a different turn,” he says, referring to his position as a prosecutor during the postwar Nuremberg trials of Nazi war criminals.

Telford Taylor, his boss, assigned him the task of digging up evidence to prosecute Germans who had served in high-level positions in the Einsatzgruppen. As Ferencz learned, they were highly educated and certain of their innocence.

The defendant whom he knew best, Otto Ohlendorf, was rational and honest enough to admit he would commit the same genocidal crimes if given another chance. Ferencz claims he was quite “a decent chap,” except for the fact that he ordered the deaths of 90,000 Jews.

Having finished his work at Nuremberg, Ferencz was placed in charge of reclaiming Jewish properties, particularly cemeteries, in Germany. Shortly after returning to New York, where he married a Jewish refugee, he was offered a job by Taylor. He practised human rights and civil liberties law.

The last segment of Prosecuting Evil deals with Ferencz’s efforts to help create the International Criminal Court, which is headquartered in The Hague. U.S. President Bill Clinton was a firm believer in the concept, but his successor, George W. Bush, was opposed to it. As a result, the United States is not among the 124 countries that have joined the International Criminal Court. Russia, China and Israel have also chosen to boycott it.

Ferencz, of course, regrets the U.S. decision, but remains absolutely convinced of the court’s relevancy and of the need to attain peace by means of law rather than by the force of war.