Queen Isabella’s legacy is nothing if not checkered.

Consider her virtues and failings:

She paved the way for the unification of Spain after having subdued the last remaining Islamic kingdom in the country. She launched the Spanish Inquisition and drove Jews and Muslims out of Spain. She sponsored Christopher Columbus’ voyage to the New World, thereby laying the foundation for Spain’s sometimes brutal colonization of the Americas.

Isabella, her rule extending from 1474 until her death in 1504, amassed an extremely mixed record. Nonetheless, as Kirsten Downey suggests in her splendid and nuanced biography, Isabella — The Warrior Queen (Doubleday), she was arguably one of Spain’s greatest monarchs, her oozing blemishes notwithstanding.

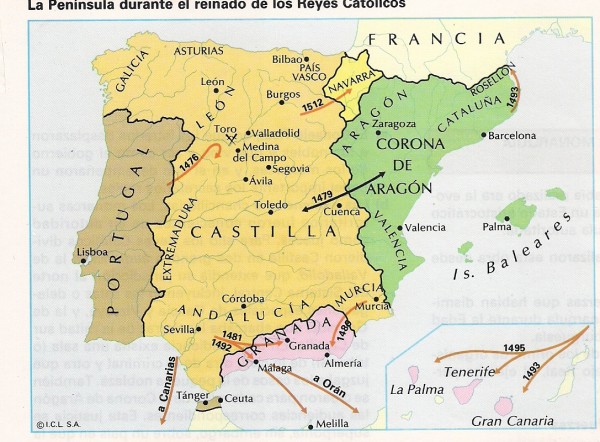

She ascended to the throne of Castile and Leon at the tender age of 23, when the Iberian Peninsula faced peril. The Ottoman Empire was on the march, threatening Christianity in southern and eastern Europe. Granada, the Andalusian Muslim kingdom, was a challenge to the notion that Spain was a Christian nation.

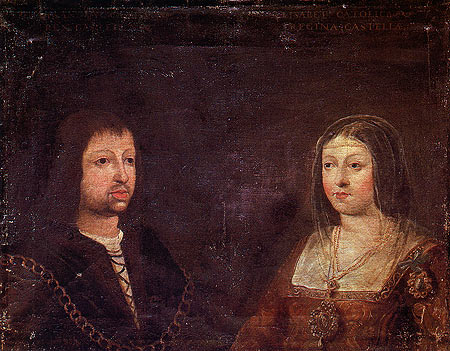

Isabella and her husband, Ferdinand, confronted these threats as a team, though he garnered much of the credit. Downey, in this book, focuses her attention on Isabella to make sense of what transpired during this seminal epoch.

Isabella’s obsession with the specter of Islam should be seen in its proper historical perspective. Much of Spain had been conquered by Muslim armies in the eighth century, leaving Christians with little more than a beachhead in the northern enclave of Asturias. By the 10th century, with the Christian reconquest having begun, Spain was split between Christians in the north and Muslims in the south.

Playing the game of divide-and-rule, Muslim conquerors initially placed local Jews in charge of cities they had captured. “For the Jews, life under the Muslims brought a marked improvement over the abuse they had suffered under the Visigoths,” Downey writes.

The Visigoths, a people of Germanic stock who had swept into Spain centuries earlier, had generally mistreated Jews. Consequently, Jews were disposed to cooperate with the new Muslim order. To Christians, the Muslim-Jewish alignment, such as it was, became a source of simmering resentment. Yet, as Downey points out, Muslim tolerance could be fickle, too. In 1066, Muslim rioters destroyed the Jewish community of Granada, killing thousands of Jews.

Jews fared little better in Christian areas of Spain. In 1391, about 60 years before Isabella’s birth, a tide of antisemitic fanaticism, centred in Seville, caused the deaths and conversions of many Jews and the destruction of innumerable synagogues.

During Isabella’s 30-year reign, the Jewish question in Spain revolved around the issue of Jewish converts. Known as conversos, they were the descendants of Jews who had converted to Christianity under duress. Some of the conversos wholeheartedly adopted Catholicism, but others converted only out of expediency. Having outwardly abandoned Judaism, the conversos moved into lucrative and influential jobs in the government and in the hierarchy of the church, becoming priests, bishops and even cardinals.

“Their success, both financially and professionally, stirred jealousy among longtime Christians, who faced new competition for positions that had once been granted almost as a matter of inheritance, from Christian father to Christian son,” says Downey, an American journalist. “Even those conversos who were devout Christians sometimes aggravated the tensions by holding themselves apart or viewing themselves as superior. The concept of lineage loomed large in their minds, as it did in the minds of Christians.”

Isabella, who had close and friendly relationships with practicing Jews and conversos, does not appear to have been an antisemite, Downey claims. Ferdinand, she adds, may have been a converso himself.

Isabella, who looked to the church for moral guidance, created the Inquisition in 1480 to ferret out and punish insincere conversos, not to persecute practicing Jews. Clerics in Seville and elsewhere had told her that heresy among conversos was undermining Christianity and the security of the state, at a time when the Ottomans were rampaging through Europe.

The first victims of the Inquisition, which, ironically, was administered by a converso, were conversos who had continued to follow some Jewish customs. But with the passage of time, the Inquisition washed over Catholics of Muslim heritage, Protestants, political dissidents and homosexuals.

Practicing Jews were specifically targeted when Isabella and Ferdinand decided that their presence was leading conversos astray. As a result, in 1492, they decided to force Jews — some 80,000 — to convert to Christianity. “Those who did not accept baptism were compelled to leave. Later, the same thing happened to the Muslims,” says Downey.

Isabella had no regrets about the Inquisition, though she admitted it had caused “great calamities and depopulated towns, provinces and kingdoms.” She justified this cruel measure on the grounds that it would protect the Christian faith.

Downey agrees: “She was a religiously fervent Catholic, living in an era when the Ottoman Turks seemed on the verge of wiping Christianity off the map. I am convinced that much of what she did was a reaction to this perceived threat, and to her belief that she was being called upon to bolster the faith against a very formidable enemy.”

Isabella was just as heartless in dealing with the Muslim residents of her kingdom. After Granada surrendered, she and Ferdinand promised Muslims they could keep their possessions and homes, maintain their mosques and preserve their customs, language and style of dress.

“Almost immediately afterward, Isabella began pressing Muslims throughout the former emirate to convert, and within ten years, she and her husband had completely retracted the pledge they had made to them,” she writes. “She thought she had a spiritual obligation … to evangelize and increase the number of Christians. She could also justify it on the basis that it was dangerous to have a large Muslim population in the south of Spain — they might welcome an Ottoman Turk invasion. But the Muslims of Granada, understandably enough, felt they had been deceived.”

Isabella’s sponsorship of Columbus’ voyages to the New World was inspired, in part, by a desire to shore up and expand the reach of Christianity. A visionary, she appreciated the significance of colonizing the Americas with Spaniards. She thereby set into motion “one of the most dramatic population shifts in history,” a process that turned Spain into the wealthiest and most powerful nation in the world for the next two centuries, Downey notes.

Spain, after Isabella’s passing, temporarily sank into decline. But building on the foundations she had laid, Spain became the world’s first “truly global superpower,” as well as an incubator of art, literature and architecture.

In sum, Isabella irretrievably blackened her name by instituting the Inquisition and ordering the expulsion of Jews and Muslims. But in uniting Spain and financing the voyages that led to the discovery of the Americas, she will always be remembered by some as a giant in the pantheon of Spanish history.