Syria and Iraq, two of the most important countries in the Arab world, have fallen into an abyss of unbridled strife and violence.

The American-Anglo invasion of Iraq in 2003, resulting in the ouster of its president, Saddam Hussein, touched off a deadly Sunni insurgency that was successively taken over by Al Qaeda and Islamic State.

With the eruption of the civil war in Syria in 2011, Shi’a militias flooded in to prop up the tottering Syrian regime of President Bashar al-Assad. This prompted Iraqi Sunni jihadists belonging to Islamic State to penetrate Syria, broadly backed by Russia, Iran and Hezbollah. By the summer of 2014, the Islamists had established a caliphate in eastern Syria and western Iraq.

The confusion and chaos that gripped Iraq and Syria in the wake of these momentous developments is the subject of William Harris’ thoroughly researched and cogent work, Quicksilver War: Syria, Iraq and the Spiral of Conflict, published by Oxford University Press.

Syria, with a population of about 22 million, has been particularly affected by these troubles. More than 400,000 Syrians have been killed, five million have fled to neighboring nations like Lebanon and Jordan and six million have been internally displaced. Not since the 1947 war in the Indian subcontinent has one country been subjected to such extreme upheaval.

As Harris points out, Syria and Iraq were two peas in a pod, politically speaking at least. Governed by secular, totalitarian Baathist regimes, which championed a blend of nationalism and socialism and cultivated hostility toward Israel and the West, they fostered a culture of absolutism and intolerance typical of a police state.

The still ongoing Syrian civil war, which started as a series of street uprisings, is devilishly complex. Comprised of various confrontations, it pits the Syrian government against an assortment of rebel groups, rebels against each other, jihadists against everyone else, Sunnis against Shia’s, and Kurds against Arabs and Turks.

The complexity of the war was heightened by several variables: the two major superpowers, the United States and Russia, intervened. Foreign volunteers flocked to the ranks of Islamic State. Countries ranging from Israel to Turkey were inexorably drawn into the conflict.

This is a war that could have been nipped in the bud had cooler heads prevailed.

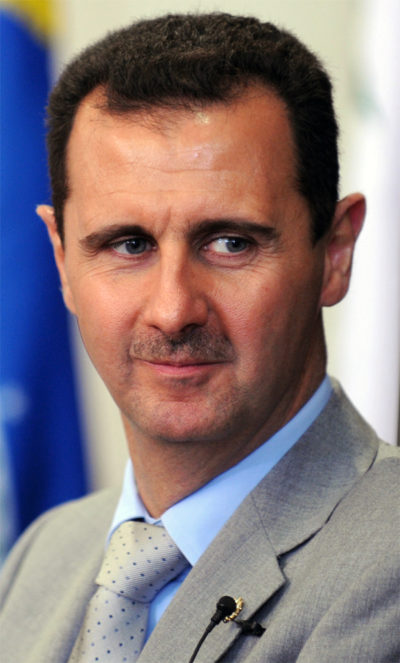

When Bashar al-Assad succeeded his father, Hafez, in 2000, he was widely regarded as a reformer who would relax political controls and improve the economy. For a brief period, he allowed a “Damascus spring” of salon gatherings and criticism of corruption and administrative failings. But when the process went too far, it was terminated.

Peaceful protests broke out and were quashed ruthlessly, leading to unprecedented bloodshed. Assad could have defused the situation, says Harris, a scholar from New Zealand. But he was loathe to show “weakness” and resorted to brute force to suppress the protests. He then accused a small, fanatical minority of foreign-inspired malcontents of sedition and treason. In a display of moderation, he lifted the 48-year-old emergency law and made constitutional adjustments, but by then it was too late.

Assad, a member of the minority Alawite sect, has been staunchly supported by his fellow Alawites, who despise the jihadists. Initially, many Christian Syrians endorsed the objectives of the revolt, but changed course after realizing that Assad was preferable to Islamic State.

Fearing that Syria would be targeted by the Americans after their occupation of Iraq, Assad decided it would be prudent to sow instability in the region by supporting the Sunni rebellion in Iraq. As a result, he permitted Arab jihadists to cross into Iraq by way of Syria. They added heft to the rebellion.

Harris believes that Assad enjoys advantages that will contribute to his ultimate victory. He has a monopoly on air power. He possesses far more heavy weaponry. And he can rely on the absolute commitment of Iran and Russia, both of which have contributed men and materiel to the battles his armed forces have fought.

Israel is carefully watching events in Syria because Iran and Hezbollah, its strongest enemies, are interested in establishing bases near its border. Israel has therefore struck Hezbollah arms convoys and Iranian formations in Syria. In Harris’ estimation, Russia has tolerated Israeli strikes because it wants Hezbollah’s wings clipped and is uncomfortable with Iran’s “sectarian predilections.”

He appears to agree with the view that Iran seeks to build a land bridge under its hegemony from Iraq to Syria and Lebanon in a bid to become the primary regional power.

But he believes that Iran’s schemes may backfire. As he puts it, “It is not easy to imagine the anger that millions of battered, humiliated, displaced Syrians who sympathized with the insurrection feel toward the Iranian regime, which joins Assad in wanting them scrubbed out of history.”

He suggests that the U.S. withdrawal from Iraq in 2011 left the field open to Islamic State and Iran, Washington’s nemeses. Islamic State was beaten back by the Iraqi army, U.S. air power and pro-Iranian Shi’a militias commanded by Qasem Soleimani, the head of Iran’s Quds Force.

Ironically, as Harris correctly observes, Iran now wields more influence in Iraq than at any other time in the recent past.