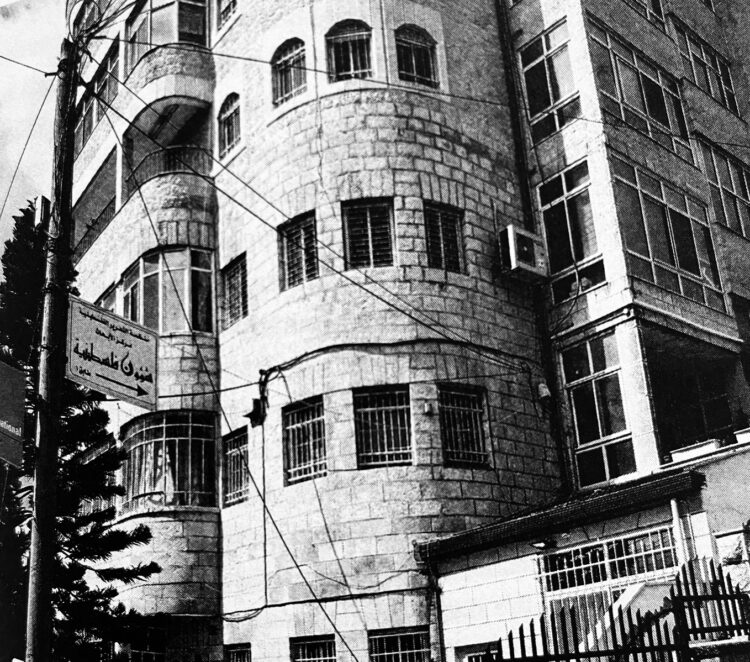

As Israeli troops swept into West Beirut in mid-September of 1982, they raided a high-rise building housing the offices of the Palestine Liberation Organization’s Research Center on Colombani Street in the heart of the cosmopolitan Ras Beirut neighborhood. In short order, they seized a vast library of books about Israel, Zionism, Judaism and Jews and an invaluable archive relating to Palestinian Arabs.

Founded in the winter of 1965, a few months after the creation of the PLO itself, the center’s mission was to study the Palestine question and to increase knowledge about the Palestinians’ enemy, Israel. It achieved these objectives through the efforts of researchers who produced a succession of books, pamphlets and academic magazines on these interrelated topics in Arabic, English and other languages.

Jonathan Marc Gribetz, an associate professor in the Department of Near Eastern Studies and the Program in Judaic Studies at Princeton University, has written a comprehensive and lucid account of the center and the Israeli raid that altered the trajectory of its existence. Reading Herzl In Beirut: The PLO Effort To Know The Enemy (Princeton University Press) “explores the role played by knowledge in the development of politics and by politics in the production and distribution of knowledge in the Palestinian-Israeli conflict,” the author writes in the introduction.

Gribetz accidentally “stumbled upon” the center during a fellowship at the University of Toronto, where he was finishing a book on Zionists and Arabs in late Ottoman Palestine. Rummaging through the library’s stacks, he found the Arabic language edition of The Zionist Idea, a volume of essays by different authors. Published by the center in 1970, it was compiled by the Jewish American historian Arthur Hertzberg.

As Gribetz observes, researchers in the center were generally hostile to the subjects they studied so assiduously. Yet oddly enough, the center was a pioneer in the field of Israeli studies, having been established two decades before the Association of Israel Studies. Subsidized by Arab governments, the Arab League and the Palestine National Fund, it played an important role in the history of the PLO, in Palestinian intellectual ferment, and in the Palestinians’ conflict with Israel.

Beirut, being a major academic and intellectual hub and a refuge of Palestinian refugees, was a propitious site for the center. Occupying six floors of a seven-storey building, it employed more than 80 researchers in ten different departments and had published some 340 books at its zenith by the late 1970s.

The titles ranged from State and Religion in Israel and Israel and World Jewry to David Ben-Gurion and The Talmud and Zionism. As well, researchers examined the ideas of the founder of modern political Zionism, Theodor Herzl, explored “the place of race and racism within Zionism,” analyzed the Israeli armed forces, and studied the place of terrorism in the Zionist movement.

In addition, the center published several periodicals, the most prominent of which was Palestinian Affairs.

Its library dealt with every conceivable aspect of Zionism, Israel and Jews. Its archive contained, among other rare items, the papers of Haj Amin al-Husseini, the Mufti of Jerusalem, and a collection of Mandate statistics regarding land ownership in Palestine.

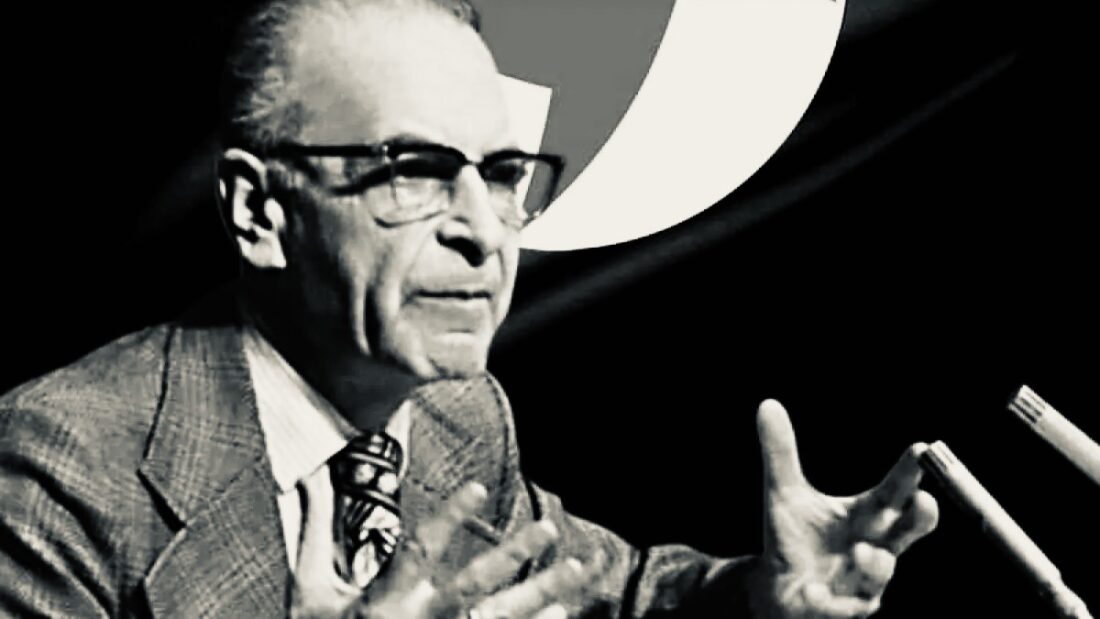

Its first director, Fayez Sayegh, was born in Tiberias, in British Mandate Palestine, in 1922. Like all but one of its directors, he was a Christian. A graduate of the American University of Beirut and Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., he believed it was crucial to study and know the enemy.

“The research could be used … by foreign media to refute the enemy’s arguments, to provide information about the roots of the issue, or to demonstrate Arab rights,” says Gribetz. “The research could also be employed by Arab media to strengthen consciousness and faith. Political institutions might use the research for political and practical planning. The information gathered could also prove beneficial to Arab states and the Arab League.”

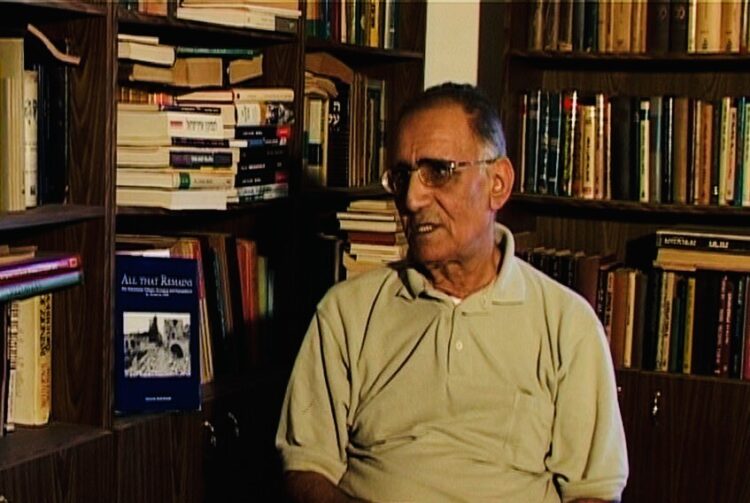

Sabri Jiryis, one of Sayegh’s successors, was born in 1938 in Fassuta, a Greek Catholic Melkite village in Palestine. During the 1948 Arab-Israeli war, Fassuta was conquered by Jewish forces and then incorporated into Israeli territory. Jiryis was admitted to the Hebrew University in 1957, one of only 48 Arab students on campus, and graduated with a law degree. As a lawyer based in Haifa, he challenged the various forms of legal discrimination Israeli Arabs experienced during Israel’s early years of statehood.

Jiryis fell afoul of the Israeli government and voluntarily left the country, settling in Beirut and becoming the PLO’s resident expert on Israeli, Zionist and Jewish affairs. Yasser Arafat, the chairman of the PLO, appointed him director of the Research Center, a post he held until his expulsion from Lebanon in 1983. In 1994, following the euphoria set off by the 1993 Oslo agreement, he returned to Fassuta.

On September 14, 1982, Israeli forces conquered West Beirut, the home of the Research Center. On the same day, the Phalange, a Lebanese Christian militia allied with Israel, massacred hundreds of Palestinians in the nearby Sabra and Shatila refugee camps.

The Israeli commander, Baruch Spiegel, informed intelligence officials of his discovery. Operatives combed through the library and the archive. Although they found nothing of importance, they carted away the materials and shipped them to Tel Aviv.

As Gribetz points out, this was not the first time the centre had been attacked. On December 10, 1974, three PLO facilities, including the center, suffered heavy damage after rocket attacks ascribed to Israel by the PLO.

Within days, Western wire services reported Israel’s raid. Jiryis complained that Israel had “plundered our Palestinian cultural heritage.” UNESCO, a United Nations body, condemned the seizures as a “deplorable act of violence … against the educational and cultural values of the Palestinian people.”

Israel’s raid on the Research Center was a public relations and diplomatic fiasco. It came on the heels of the harsh condemnation directed at the Israeli government for the Sabra and Shatila massacres. In an attempt to justify the seizures, the mass-circulation Israeli daily Ma’ariv published a piece claiming that the center was also a PLO intelligence gathering facility to facilitate terrorist acts.

The Jewish novelist Cynthia Ozick, in a strongly-worded article in The New York Times, endorsed this allegation, branding the center as “a leading” PLO intelligence site.

Gribetz advances a more nuanced theory. “Those who regarded the PLO as a legitimate national liberation movement relied on the descriptions of the center as a legitimate academic research institution. Those who regarded the PLO as an illegitimate terrorist organization relied on sources indicating that the center’s academic research was but one of its ‘two faces’…”

In his estimation, the center was a think tank that “straddled the spheres of academics and politics, under the umbrella of an organization that … engaged in a violent struggle against an enemy.” In other words, he adds, it “occasionally prepared operational intelligence for attacks on Israel.”

On November 24, 1983, nine months after the center was severely damaged by a mysterious car bombing that killed eight people, Israel returned its library and archive as part of a prisoner exchange. In exchange for the release of six Israeli soldiers who had been captured by the PLO during Israel’s invasion of Lebanon the year before, Israel released about 4,400 Arab prisoners as well as the materials in the center.

Israel, having concluded that its collection was worthless from an operational point of view, had no problem giving it up.

The collection, stuffed into more than 100 wooden crates, was turned over to the Red Cross and loaded into the cargo holds of three Air France passenger planes sitting on the tarmac of Ben-Gurion Airport and bound for Algiers. The Arab prisoners boarded the same airplanes.

By this point, the center was no longer in Beirut, having relocated to Algiers after the expulsion of the PLO from Lebanon.

According to Jiryis, Israel returned absolutely everything. However, an Israeli official told Gribetz that one of its items, a 17th century Hebrew manuscript from Yemen, was turned over to the National Library in western Jerusalem.

Gribetz speculates that the Moshe Dayan Center for Middle Eastern and African Studies at Tel Aviv University may have appropriated Arab periodicals from the center.

In 2011, on orders of Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas, the center was restored in the West Bank town of Ramallah. Gribetz visited it in 2018 and found neither a library nor scholars hard at work.

Having been informed that the center’s collection was still in Algiers, Gribetz asked a PLO official why it had not been transferred to Ramallah. He mentioned three reasons:

“First, in order to make the transfer, someone would need to go to Algiers to check the condition of the materials, an effort that would demand significant resources. Second, the books that had been in the library were now generally available in Palestinian libraries … Many of these books had even been scanned and made available online. Third, and finally, the tens of thousands of books that had been housed in Beirut would not fit into the modest one-storey office where the Research Center was now located.”

The explanation, though convincing, points to only one irrefutable conclusion: the center, as it existed in Beirut during its glory years prior to Israel’s raid, is now a pale imitation of its former self and probably will be never resurrected.