She was a radical revolutionary and a professional agitator.

Emma Goldman, a headstrong woman of conviction and resolve, was an advocate of free speech, free love and birth control in an era when such liberties were usually regarded as subversive. Above all else, she was an anarchist, a non-conformist staunchly opposed to capitalism.

Her life and times are expertly explored in Emma Goldman, a PBS “American Experience” encore documentary to be broadcast on Tuesday, May 21 at 9 p.m.

Born in 1869 in Lithuania, then part of the Russian empire, Goldman was a rebel with a cause. Fleeing an arranged marriage, she immigrated to the United States, hoping it would be the place where the embers of a revolution could be ignited.

There she met Alexander Berkman, a kindred spirit who would be her life-long friend, and Johann Most, an inspirational German-American anarchist with a large following who would be her mentor.

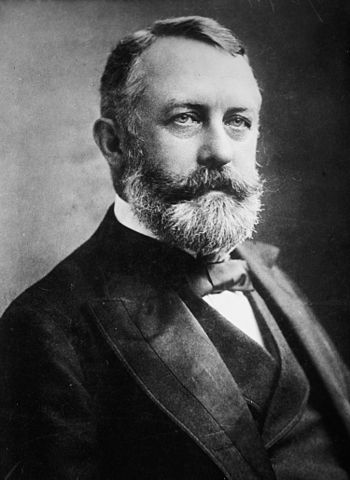

Justifying acts of violence when only absolutely necessary, Goldman supported Berkman’s attempt in 1893 to assassinate Henry Clay Frick, the general manager of a massive Carnegie steel plant where workers had gone on strike. He was imprisoned for 22 years. She was arrested and jailed for a year, convicted of incitement to riot.

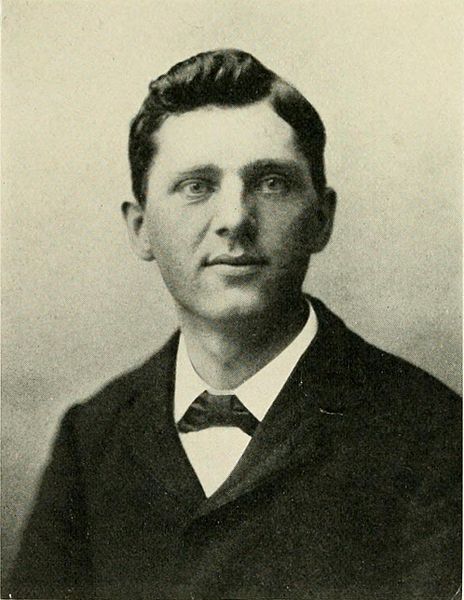

In 1901, an anarchist named Leon Czolgosz assassinated U.S. President William McKinley, claiming he had been “set on fire” by Goldman. She defended Czolgosz, damaging the American anarchist movement. Criticized even by labor unions, she withdrew from the anarchist movement and began working as a nurse on the Lower East Side, a teeming neighborhood populated by Jewish newcomers like herself.

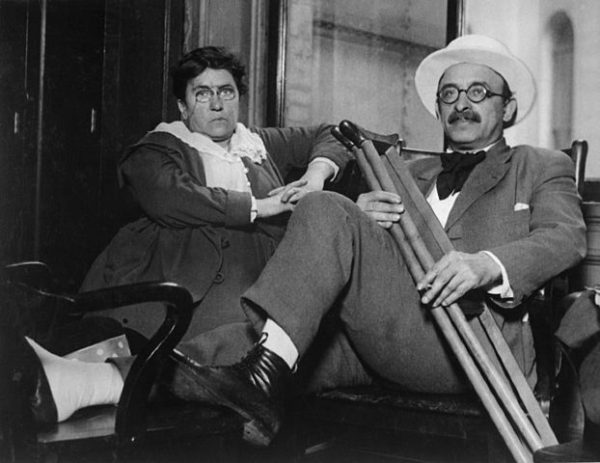

Goldman launched Mother Earth, an anarchist magazine in 1906, the year Berkman was released from prison. In 1908, at the age of 40, she met Ben Reitman, a physician and social reformer. For the next number of years, they spent much of their time on the road as Goldman earned a living as a popular public speaker.

She and Berkman railed against the entry of the United States into World War I in 1917, regarding it as a morally wrong cause that could only serve the class interests of oligarchs. Charged with conspiracy to violate the Draft Act, they were imprisoned for 22 months.

The so-called Palmer raids in 1919 resulted in the arrests of more than 200 radicals, including Goldman and Berkman. In December of that year, they were deported. Goldman, having lived in the United States for 34 years, was devastated.

Goldman and Berkman went into exile in the Soviet Union in 1920, only to be disillusioned by the tyranny of the Bolshevik revolution. Thrown into intellectual exile after leaving the Soviet Union in 1921, she conceded that the revolution had failed.

Friends bought her a cottage in St. Tropez, France, but she longed to return to America, where her ego had been stroked by adoring audiences. With the publication of her memoirs, Living My Life, she was temporarily allowed to visit the United States, but she spent her final years in Toronto. She suffered a stroke on February 17, 1940 and died about three months later.

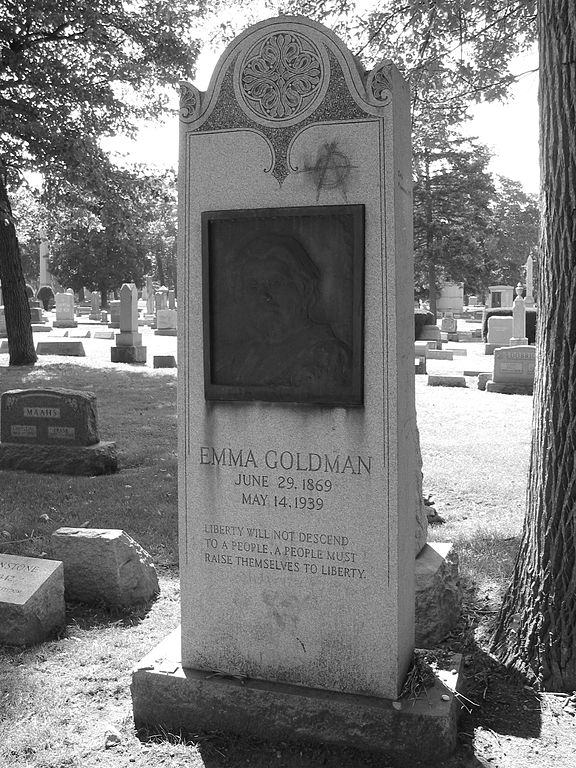

She was buried in Chicago’s Waldheim cemetery, the final resting place of the trade unionists who had ardently supported her during her heyday as a firebrand.