November 9 is a Schicksalstag, a fateful day, a shameful day, but also a happy day in German history.

On November 9, 1918, Philipp Scheidemann proclaimed the first German republic from a window of the Reichstag. This proclamation raised the hope that Germany, after the defeat in World War I and the resignation of the kaiser, could build a stable democracy and regain the trust of its neighbours and the world.

Not even 15 years later, on January 30, 1933, the Weimar Republic failed because of too little support from the German population. Hitler came to power and built his dictatorial regime with too much support from the German population.

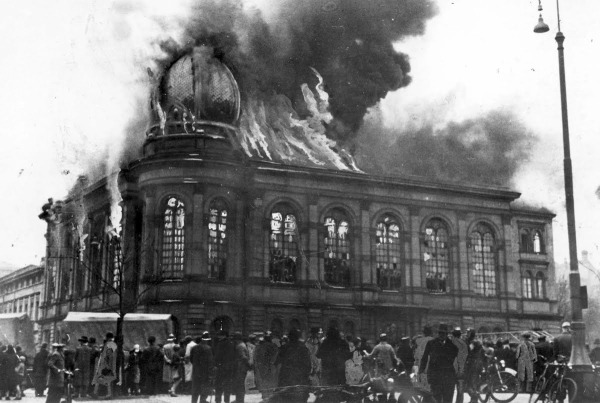

Seventy-six years ago, on November 9, 1938, during Kristallnacht, synagogues and Jewish property were burned and destroyed, more than 1,300 Jews were killed, and the inexorable road to the Holocaust and the killing of six million European Jews started — with too many German citizens looking the other way or even approving.

Today, Germans bow their head in respect, grief and shame to the victims of the Holocaust.

Twenty-five years ago, on November 9, 1989, the Berlin Wall opened and a process started that eventually led to German reunification and the end of the cold war.

Those who demonstrated in the streets of Leipzig and Berlin against an oppressive East German communist regime may have been the grandchildren of Germans who supported the Weimar Republic or fought against it. They may have been the children of Germans who tolerated or even supported the atrocities of the Nazi regime. Just a few may even have been children of parents who followed their conscience, resisted the regime and protected their Jewish neighbours.

More often than not, family histories contain a mixture of all these different backgrounds. But whatever the rights and wrongs in the history of their families, Germans in 1989 had to decide and do right in their moment in history — and they did. But doing right today can only be guided by awareness of the burden of our German history.

A history that on the same day, the ninth day of November, makes us wistful because of the failure of the first German republic, shameful because of the atrocity of Kristallnacht and the Holocaust, and joyful because of the fall of the Berlin Wall and Germany’s reunification.

It is this mixture and ambivalence that will forever be connected to German history in general and to the ninth of November in particular. This ninth of November reminds us that ours is a history that carries a burden of guilt. But since 1989, we can perhaps hope that this date might one day stand not only for guilt and atonement but also for redemption. Because how can we live without the hope for redemption? But what would be the value of redemption without the weight of memory?

In this knowledge we will responsibly shape our future — in Germany, in Europe, in the world. Let me emphasize that this includes in particular Israel and the Jewish community.

Walter Stechel is consul general of the Federal Republic of Germany in Toronto.