Thirty one years ago, on a bright sunny afternoon in Tel Aviv during the first week of December and only days before the first Palestinian uprising broke out, I found myself in the presence of one of Israel’s most iconoclastic and idealistic figures, Uri Avnery.

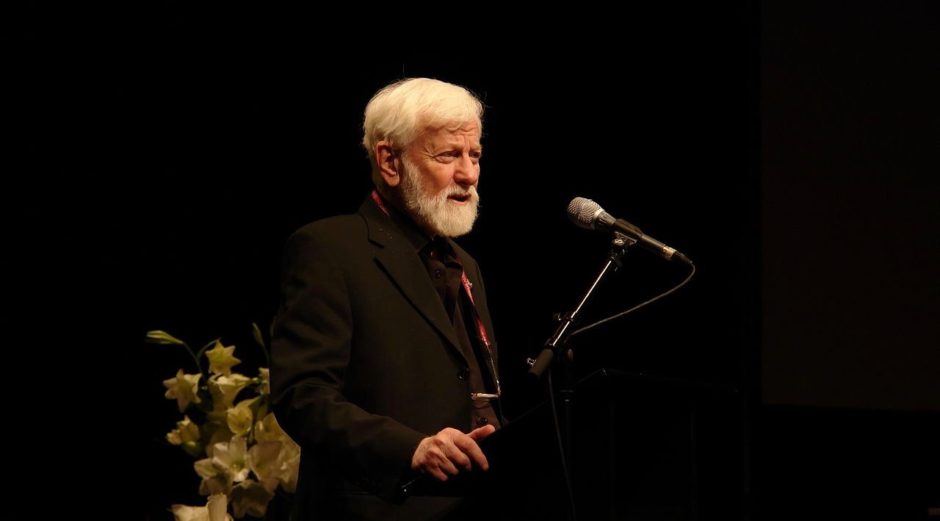

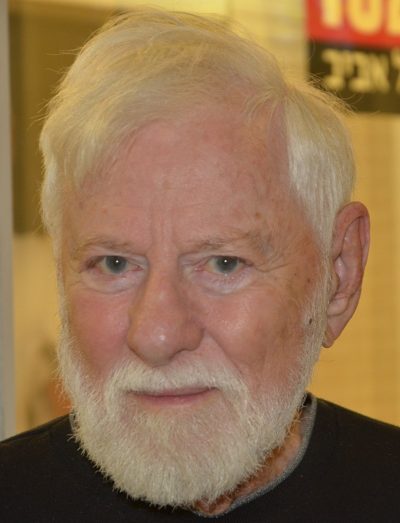

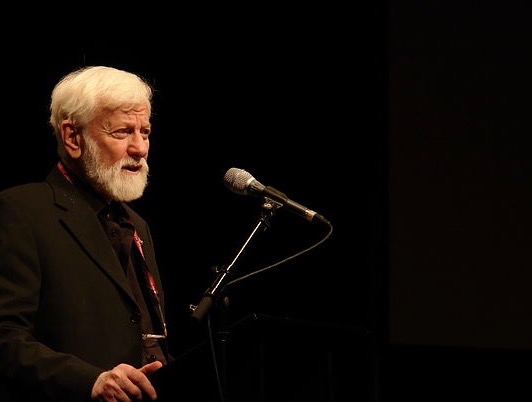

Avnery, who died on August 20 at the age of 94, was a journalist, peace activist and politician loved and hated by Israelis.

I had come to interview Avnery for a profile I would write for a Canadian newspaper. The article would appear in a special supplement to mark Israel’s 4oth anniversary. Being broadly familiar with his career, I looked forward to meeting him in person.

Of medium height, with a shock of snow white hair, he welcomed me into his spacious living room, which was filled with books and offered a stunning panoramic view of the shimmering Mediterranean Sea. He spoke fluent English with a distinct German accent, a residue of his boyhood in Germany.

He reminisced about his contributions to Israeli journalism, his early years in Mandate Palestine, his political transformation from rightist to leftist, his efforts to reconcile Israel and the Palestinians, and his quest to bring peace to Israel.

The views he espoused remained with him until his death.

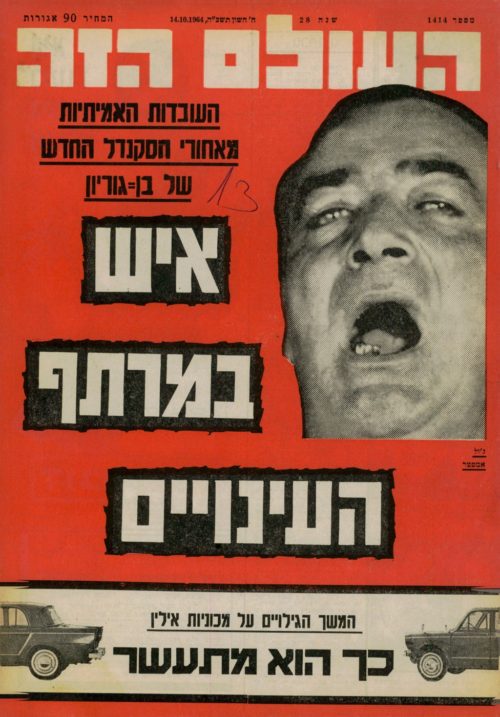

Avnery will always be inextricably associated with Haolam Hazeh (This World), the irreverent weekly magazine of which he was editor-in-chief and publisher. Before he and an associate took charge of this ailing family journal in 1950 and turned it into a zippy, muckraking periodical, Israeli newspapers and magazines were smug and boring and stylistically as exciting as Pravda, the organ of the Soviet Communist Party.

With its heady mix of political exposes, society gossip, literary reviews and occasional pinups, Haolam Hazeh shocked and titilated a nation and revolutionized journalism in Israel. “No one denies we changed the face of it by creating a new Hebrew vernacular style — a style that has been adopted by everyone in Israel,” he said.

He shrugged. “But today, we’re very conservative compared to other Israeli publications.”

Boasting a readership of 140,000, Haolam Hazeh — which folded in 1993 — appealed to a certain segment: the educated, well-t0-do, second generation Israeli. As Avnery pointed out, the average reader expected to be enlightened, jolted and entertained. Under its slogan, “Without fear, without hypocrisy,” it was a thorn in the side of the powers-that-be.

Apart from consistently calling for an Arab-Israeli peace agreement based on Israel’s withdrawal from the occupied territories and the establishment of a Palestinian state in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, Haolam Hazeh, in rigorously-researched articles, focused on major scandals that reverberated through Israel’s body politic.

It published the incriminating facts about the lingering Lavon affair, which led to the downfall of Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion’s government. It exposed wrongdoing by banking and government officials, who played a role in the downfall of Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin. It called attention to the illegal archaeological digs of Defence Minister Moshe Dayan.

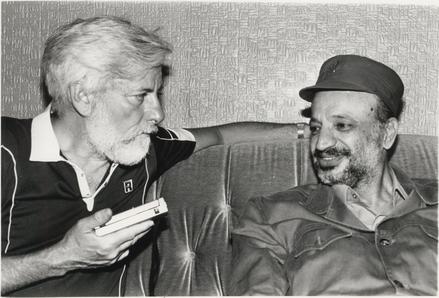

Much to Avnery’s satisfaction, Haolam Hazeh was the first Israeli magazine to obtain an exclusive interview with Yasser Arafat, the chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization (and, from 1994 until his death in 2004, the first president of the Palestine Authority).

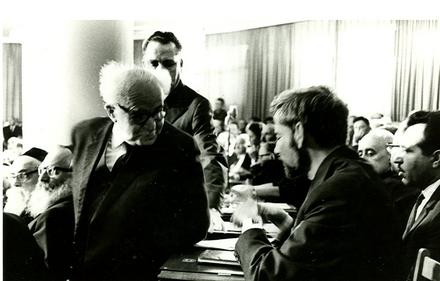

The sensational scoops made him enemies. Ben-Gurion was one of them, refusing to utter Haolam Hazeh’s name and banning government advertisements in its pages.

Ben-Gurion was infuriated with Avnery because he had accused him of three cardinal sins — failing to create a genuine democracy by treating Israeli Arabs unequally, falling short of ensuring equality between Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jews, and leaving Israel without a written constitution.

Avnery’s fiercest critics resorted to violence.

In 1952 and 1955, his editorial offices and printing plant were bombed. In 1953, an attacker broke his fingers. In 1957, a knife-wielding assailant wounded him. In 1972, a fire consumed Haolam Hazeh’s archives.

Since then, his foes have left him alone. “The last few years have been quiet,” he said. “Israel is not a very violent country, really.”

He claimed that these attacks neither intimidated him nor forced him to dilute the contents of Haolam Hazeh. “I’m not too concerned,” he said.

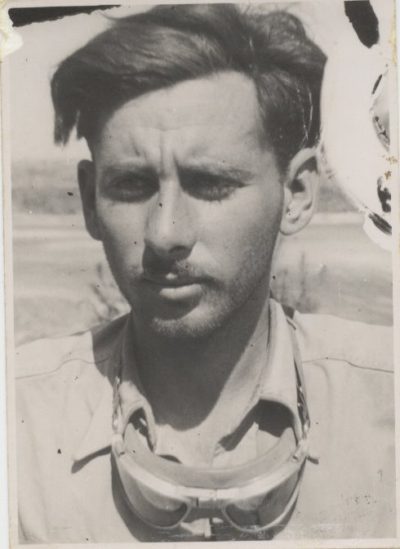

Avnery, whose original name was Helmut Ostermann, was born in the town of Beckhum in 1923, the son of a banker who settled in Palestine immediately after the Nazi takeover of Germany in January 1933. He joined the Irgun Tzvai Leumi, a right-wing Zionist militia, but left soon afterward due to his dissatisfaction with its policy toward Palestinian Arabs.

On the eve of the 1948 Arab-Israeli war, he published his first work, a booklet titled War or Peace in the Semitic Region, in which he advocated an alliance of the Hebrew and Arab national movements. In calling for a Semitic confederation, he broke new ground, making a distinction between the “Israeli nation” and the “Jewish people.” In effect, Avnery argued that Israeli Jews and Diaspora Jews have no common history and destiny. As he put it, “We Israelis are a different nation, with our own set of peculiar problems.”

He denied being anti-Zionist, his book Israel Without Zionists notwithstanding. “I want Israel to exist, with a Jewish majority and strong ties to the Diaspora. Israel doesn’t belong to the Jewish world, but any Jew should be able to immigrate to Israel and be a citizen.”

Avnery contended that the Law of Return — which allows virtually any Jew around the world to claim Israeli citizenship — was a mistake. Yet he would not repeal it. “It’s become a symbol of Jewish statehood.”

When the War of Independence erupted, he joined the Givati Brigade of the Haganah, the fighting force of Palestine’s Jewish community. Severely wounded by Egyptian gunfire in the final days of the war, he spent several months convalescing in a hospital.

Throughout that conflict, he jotted down his reflections, which were published in a bestseller, In the Fields of Philistine. The sequel, The Other Side of the Coin, was a flop. Since then, he’s written a succession of books.

Having recovered from his wounds, he joined the staff of the left-of-center daily newspaper Haaretz as an editorial writer. Within a year, he quit, disillusioned that his articles on Israel’s expropriation of Israeli Arab land and property had been spiked.

He purchased Haolam Hazeh with the express purpose of creating an alternative voice for the younger generation of Israelis who rejected the status quo. “We decided on a two-pronged editorial approach — sex and scandal to draw in a readership interested in the political and social affairs of the day.”

Not surprisingly, Avnery’s iconoclasm was not appreciated by the Israeli leadership. In 1965, the government enacted a press law that, he claimed, was aimed at crippling Haolam Hazeh.

By way of reaction, he formed a political party, Haolam Hazeh-New Force Party, which espoused three principles: separation of state and synagogue, equal rights for Jews and Arabs, and Palestinian statehood in the West Bank and Gaza.

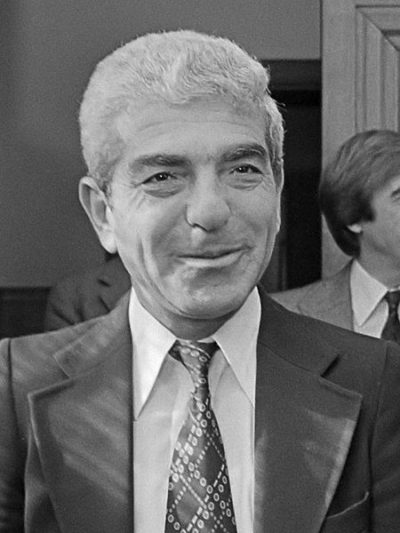

He won a seat in the Knesset, and four years later, his party picked up two Knesset seats. In 1977, he and his supporters formed a new party, Sheli, which won two parliamentary seats. He resigned in 1981, but in 1984 he became a founding member of the Progressive List for Peace, an Arab-Jewish party which acquired three Knesset seats.

During a decade in parliament, he made more than 1,000 speeches, calling for reform in nearly all spheres of law and administration.

In his quest to begin a dialogue with the Palestinians, Avnery began talking to PLO officials in 1974. Two of them, Said Hammami and Issam Sartawi, were assassinated. (Until the 1993 Oslo peace process, Israel did not recognize the PLO and forbade Israelis to maintain any contacts with its officials.)

On July 3, 1982, during Israel’s siege of Beirut, Avnery met Arafat in his bunker. But after the passage in 1986 of Israeli legislation barring contact with the PLO, he kept a low profile.

Nonetheless, he insisted that the PLO was the legitimate representative of the Palestinians. “If you’re at war, you negotiate with your enemy. It’s inevitable that Israel will deal with the PLO.” (Which is precisely what happened during the Oslo era).

A Palestinian state with open borders, he said, would pose no security threat. In his view, the PLO would coexist with Israel and “keep extremists in check.”

He was convinced that the status quo was detrimental to Israel’s interests. “Israel cannot have peace and remain in the occupied territories. Peace is absolutely essential to Israel’s existence. The occupation corrupts us. We don’t occupy the territories. They occupy us.”

Asked whether he was confident about the prospects for peace, he said, “It’s very difficult to be optimistic in the short run. But I’m a believer in Israel and, therefore, I’m optimistic.”