Egypt is synonymous with the pyramids, the tombs of the pharoahs, the ruins of ancient temples and the artifacts of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

But even discerning travellers often overlook one of Egypt’s most unforgettable attractions — the remote oases of the Western Desert, the eastern extension of the Sahara Desert.

Far from Egypt’s main cities and towns, Kharga, Dakhla, Farfara and Bahariya were rescued from total oblivion by Egypt’s late president, Gamal Abdel Nasser. Determined to funnel peasants away from the overpopulated ribbon of fertile land along the Nile River, he developed this inhospitable region by means of agriculture.

Egyptians who streamed there cultivated date palms, wheat, vegetables, rice, citrus and olives. But Nasser’s project of social engineering has not exactly been an unsurpassed success.

The Nile Delta and the Nile Valley, where much of Egypt’s population is concentrated, are still bursting at the seams, while the oases remain sparsely populated and relatively unspoiled.

For tourists seeking off-the-beaten-track and alluring destinations, this is all for the good.

Kharga, which lay on the slave route from Sudan before the 19th century, is dotted with lush date plantations, swaying wheat fields and placid cow pastures. In terms of its topography, it’s a combination of stark plains and brooding escarpments.

The two-lane road leading to Kharga takes you past Watermelon Valley, filled with thousands of rounded boulders shaped like watermelons, and the somnolent town of Qasr Kharga, whose claim to fame is the sandstone ruins of the Temple of Hibis. Built by the Persian emperor Darius, it was discovered in 1909 under a mound of sand and rubble.

Close by is a date farm, whose high season runs from September to December, and the Necropolis of Al Bagawat, a Coptic shrine containing domed mud-brick tombs. The ceilings of two of the tombs are adorned with crudely-drawn biblical scenes.

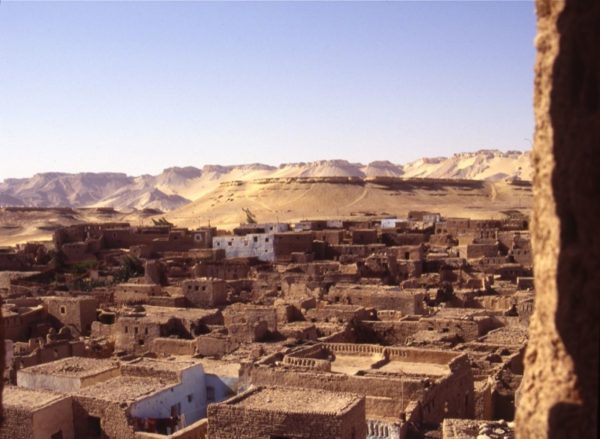

Dakhla is two-and-a-half hours by car from Kharga. The landscape between these oases is marked by lonely mesas and imposing tan mountain ranges. Cultivated patches of green break up the harsh desert terrain.

In Dakhla, the nearly deserted mud-brick village of Al Qasr is well worth visiting, a medieval warren of crumbling buildings, dark and mysterious passageways and pottery workshops. The ethnographic museum, though poorly lit, offers insights into Bedouin culture through an exhibition of clothing, jewellery, cooking utensils and hunting gear.

I also enjoyed a one-and-a-half hour camel trek through yellowish desert wastes broken up by two shimmering salt water lakes, a dip in a muddy swimming hole and a night camped out under a canopy of stars.

The lunar desert floor adjacent to my encampment was littered with small black balls, which turned out to be camel dung. As I sat around a blazing fire to ward off the chill, two Bedouin guides prepared a meal of watery lentil soup, boiled chicken, rice, potatoes and tea.

En route to Farafra, the least populated and visited oasis, the cultivated land soon gave way to a monotonous gravel plain and then an absolutely flat and eerie yellow plain. We were on the periphery of the Great Sand Sea, a foreboding and all but inaccessible and impassable region of gigantic sand dunes which sweep into Libya.

Farafra itself was unimpressive, a dusty, flyblown place where the glare of the sun was blinding at high noon. But I was intrigued by Badr Abdel Moghny Aly’s art gallery. Aly, a self-educated artist born in Farafra, exhibits his works in a spacious villa with a walled garden. He’s best known for his oil paintings, water colors and clay and palm wood sculptures of eccentric local characters.

The highlight in Farafra was indubitably the White Desert, a vista of fantastic, otherwordly limestone formations which bear an uncanny resemblance to snow and ice bergs. Think of it: “Snow” in the Western Desert!

The sheer solitude of the desert, plus the splintered rocks which tingled under my feet like broken glass, were enchanting. As in Dakhla, we camped under a sky flecked with stars. As I got ready to crawl into the sleeping bag, the mayor of Farafra showed up to greet us. On the following morning, I awoke just before dawn to find the Bedouins busily making a fire for the warm pita breads we would be served for breakfast.

Bahariya, with its six hamlets, is famous for its succulent dates. In Bawiti, the main town, I bought several boxes of dried dates to share with my family.

Aside from its massive date plantations, Bahariya is most associated with the Black Desert, an unrelieved expanse of black basalt rock which disintegrates at the touch; the crumbling and forlorn British fortress atop wind-swept Black Mountain, and the Bir Ghaba hot springs.

The scenery from Bahariya to Cairo was barren, a veritable moonscape. As we got closer to the Egyptian capital, patches of green and the faint outlines of contemporary and ancient civilizations — October 6 City, Magic Land and the tips of the Giza pyramids — appeared in the hazy distance.

The stark splendour of Kharga, Dakhla, Farafra and Bahariya suddenly seemed very far away.