On May 19, 1916, representatives of Britain and France secretly reached an accord, officially known as the Asia Minor Agreement, by which most of the Arab lands under the rule of the Ottoman Empire were to be divided into British and French spheres of influence with the conclusion of World War I.

The Ottoman Turks had entered the war on the side of Germany and Austria-Hungary. While the Turks had already lost virtually all of their European possessions, they still controlled a vast expanse of territory in the Middle East.

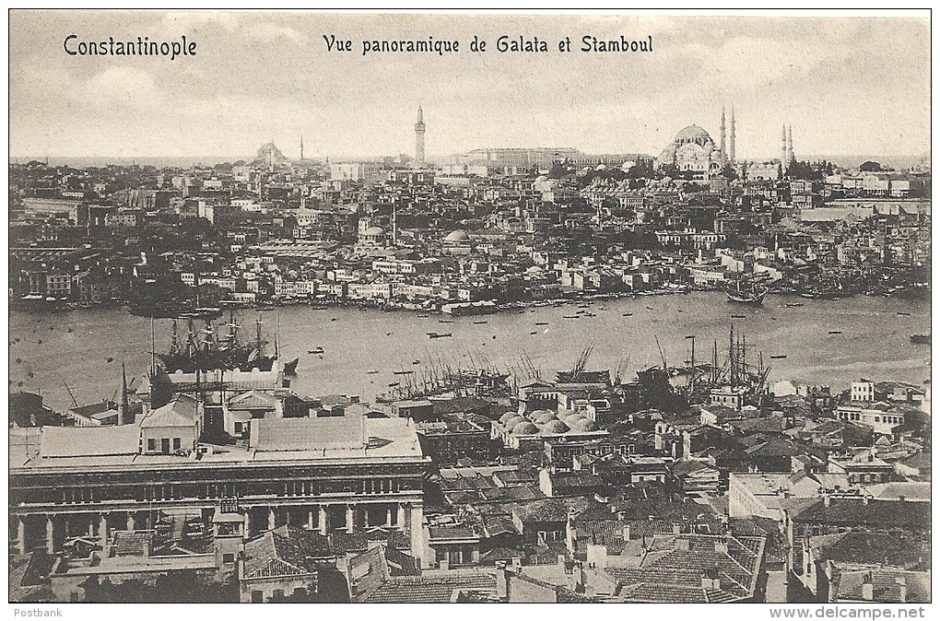

On March 18, 1915, Britain signed a secret agreement with Russia, whose designs on the empire’s territory had led the Turks to join forces with the Central Powers in 1914. By its terms, Russia would annex the Ottoman capital of Istanbul (Constantinople) and retain control of the Dardanelles, the important strait connecting the Black Sea with the Mediterranean.

In return, Russia would agree to British claims on other areas of the Ottoman Empire, including the oil-rich region of Mesopotamia.

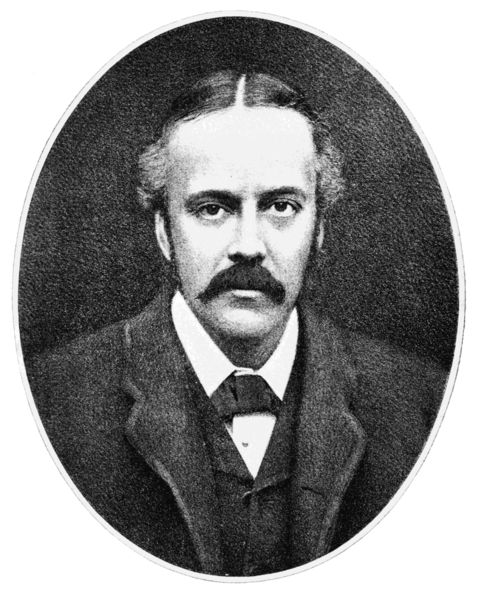

A year later, Sir Mark Sykes and Francois Georges-Picot, respectively acting on behalf of Britain and France, authored another secret agreement to divide the Middle East.

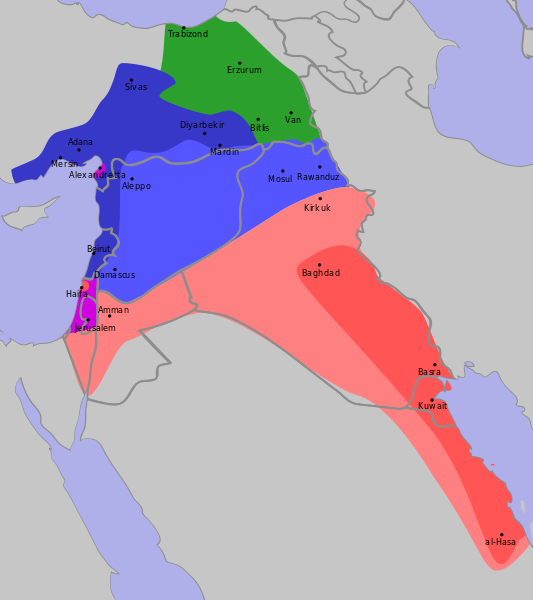

With the Sykes-Picot Agreement, as it became known, France and Britain agreed to divide up the Arab territories of the former Ottoman Empire into spheres of influence. The Syrian coast and much of modern-day Lebanon went to France. Britain would take direct control over central and southern Mesopotamia, around the Baghdad and Basra provinces.

Palestine would have an international administration, as other Christian powers, including Russia, held an interest in the region. The Russians would receive Kurdish and Armenian lands to the northeast.

The map Sykes and Picot drew up cut across ethnic, linguistic and religious lines and was formalized and made official in 1920 with the San Remo Agreement. It defined the borders of what would become Iraq, Lebanon, Palestine (after 1948, Israel), and Syria. These would all become League of Nations Mandates.

Of course, the Arabs, who had been encouraged to revolt against the Turks by Sir Henry McMahon, Britain’s high commissioner in Egypt, and T.E. Lawrence, among others, were not informed of the deal, though Arab troops played a vital role in the Allied victory over the Ottoman Empire.

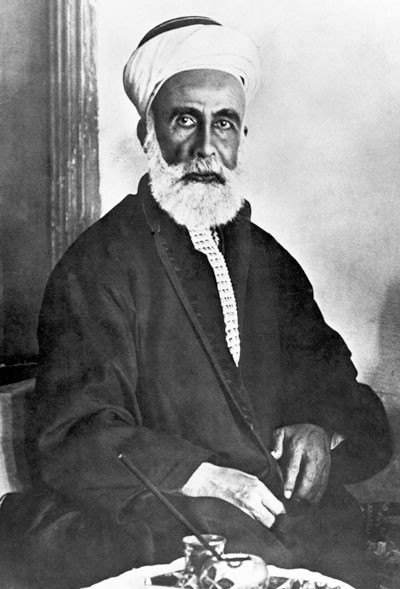

In June 1916, Sharif Hussein bin Ali, the Hashemite monarch who ruled over Mecca and the Hejaz, had initiated the Arab Revolt against Ottoman rule. His sons, the emirs Abdullah and Faisal, led the Arab forces, with Faisal’s troops liberating Damascus from Ottoman rule in 1918.

At the end of the war, Arab forces controlled all of modern Jordan, and much of the Arabian peninsula and southern Syria. They hoped to create a unified Arab state stretching from Syria to Yemen. But their aspirations would be dashed.

Arabia was, in the words of historian David Murphy, who has written about Lawrence and the Arab Revolt, to receive only “a certain level of independence.”

To further complicate matters, British Foreign Secretary Arthur James Balfour in 1917 had issued a letter to a prominent British Zionist, Lord Rothschild, promising Britain’s commitment and support for a Jewish home in Palestine.

The Balfour Declaration, which recognized the Zionist movement as the organization that would be responsible for the building of a Jewish community in Palestine, was incorporated into the Palestine Mandate awarded to Britain by the League of Nations.

Thus, the great powers, particularly Britain, made contradictory promises to their erstwhile allies and surreptitiously carved up lands they had not yet conquered, deals that went against the promises McMahon had made to Hussein.

Apart from the Arabs, the biggest losers were the Kurds, a distinct ethnic and linguistic group who weren’t given a state at all. Today the Kurdish heartland stretches into corners of Iraq, Syria, Turkey, and Iran.

“Sykes-Picot was a mistake,” Zikri Mosa, an adviser to Kurdistan’s President Masoud Barzani, has said. “It was like a forced marriage. It was doomed from the start. It was immoral, because it decided people’s future without asking them.”

Although the European powers left after World War II, the states they created remained. Pan-Arabists and Arab nationalists have condemned the “Sykes-Picot borders” ever since as artificial and illegitimate, undeserving of recognition.

Rejection of Sykes-Picot has, at times, moved from discourse into action: the United Arab Republic (Egypt and Syria,1958-1961), the United Arab States (Egypt, Syria and North Yemen, 1958-1961), and the Federation of Arab Republics (Libya, Egypt and Syria, 1972-1977) were among many attempts to create a pan-Arab alternative to the post-1918 fragmentation.

Now we have a new entity determined to erase these borders. In 2014, the militant Islamists who call themselves the Islamic State (IS) proclaimed a caliphate in the region straddling the border between Iraq and Syria. In a propaganda video, the group’s leadership chose to highlight the destruction of the border; its title was The End of Sykes-Picot.

The message of the 15-minute video is clear: a former site of division, statehood, and military might is now an unremarkable stretch of desert. By conquering this region, IS has triumphed over the institutions that once governed the area.

IS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi has boasted that the establishment of his caliphate amounts to tearing the Sykes-Picot Agreement to shreds. And at the moment, IS is stronger militarily than many states in the region.

Both Iraq and Syria have indeed fallen into virtual anarchy. Iraq is basically now three distinct regions of Sunni Arabs, Shia Arabs and Kurds. Syria has totally imploded and is now embroiled in a vicious civil war. We may eventually be confronted with a new map of new entities born or reborn.

Meanwhile, as millions of refugees flee and try to enter Europe, we might term this the “revenge of Sykes-Picot.” Indeed, not only has the mess in the Middle East rendered the 1916 deal null and void, but the European Union, now trying to deal with the influx, may itself, ironically, begin to disintegrate and so, in a sense, also fall victim to Sykes-Picot a century later.

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.