Israel has the dubious distinction of being the only country whose very existence is challenged. Given its array of enemies, ranging from Iran and Hezbollah to Hamas and Islamic Jihad, Israel has devised a policy of assassinating its foes. Since its founding 70 years ago, Israel has assassinated more people than any other Western nation. Indeed, as Ronen Bergman claims in Rise and Kill First: The Secret History of Israel’s Targeted Assassinations (Random House), Israel has developed “the most robust, streamlined assassination machine in history.”

From statehood in 1948 until the outbreak of the second Palestinian uprising in 2000, Israel conducted some 500 targeted operations, killing about 1,000 combatants and civilians. During the intifada itself, Israel carried out 1,000 extra-judicial operations. Since the end of the rebellion around 2005, Israel has executed some 800 targeted operations.

In the main, the victims have been Palestinians in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. Israel also has targeted Palestinians abroad, Egyptian and Syrian Arabs and foreign nationals.

As Bergman points out in a note about his sources, Rise and Kill First — a phrase from the Babylonian Talmud — is an unauthorized account of the Israeli intelligence service. “Efforts to persuade the Israeli defence establishment to cooperate with the research for this project went no where,” he writes. As a result, Bergman, an Israeli journalist, relies on information obtained from 1,000 interviews with politicians, chiefs of intelligence agencies and operatives themselves. They, in turn, passed on thousands of documents to him.

His assiduousness has paid off. Rise and Kill First is substantive and authoritative, probably the definitive work on the subject. Often reading like an espionage novel, it is fast paced, fascinating and hard to put down.

Israel’s eye-for-an-eye policy goes back to the British Mandate era.

Hashomer, an early Jewish self-defence force, punished Arabs for crimes against Jews, as did the Haganah, its successor. In 1946, a Haganah unit assassinated Gotthilf Wagner, a wealthy German industrialist and the leader of the Templers in Palestine. Wagner had boasted of assisting the German army and the Gestapo during World War II. Wagner’s murder discouraged the Templers from reestablishing themselves in Palestine.

In the runup to the first Arab-Israeli war, the Haganah killed Palestinians who had murdered Jews, while Lehi, a right-wing Jewish militia, assassinated Count Folke Bernadotte, a United Nations mediator who had incurred its wrath.

David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s first prime minister, personally supervised the secret activities of the Mossad and the Shin Bet, which were respectively responsible for foreign and domestic operations. Neither agency answered to parliament, citing”state security” to justify their actions.

According to Bergman, Israel’s first targeted killings claimed the lives of two Egyptian army officers, Mustafa Hafez and Salah Mustafa, in the mid-1950s. Hafez coordinated Palestinian attacks against Israel from the Gaza Strip, which Egypt administered. Mustafa, the military attache in Jordan, performed a similar role from his base in Amman.

Under the command of Isser Harel, the Mossad went after German scientists in Egypt working on missile projects. With the help of the legendary Israeli spy Eli Cohen, based in Damascus, the Mossad found the German war criminal Alois Brunner, sending him a letter bomb that seriously injured him.

During and immediately after the 1967 Six Day War, Israeli forces tried to kill Yasser Arafat, the leader of the Palestine Liberation Organization. Israel renewed its efforts against Arafat during and after the 1982 war in Lebanon.

Ariel Sharon, a general and a future prime minister, squelched a revolt in Gaza in 1971 by means of assassinations.

In the wake of the 1972 Munich massacre of Israeli athletes at the summer Olympic Games, Israel targeted 11 Palestinians who had been involved in it directly or indirectly. In the same year, in Operation Spring of Youth, an Israeli force led by Ehud Barak gunned down several key leaders of the PLO in Beirut. Six years later, Israeli operatives exacted vengeance on Wadie Haddad, a leader of a radical Palestinian faction. Ali Hassan Salameh, another Palestinian commander, was killed by a car bomb in Beirut in 1979.

During this period, Michael (Mike) Harari, a key Mossad operative, played an integral role in hunting down and killing Israel’s enemies.

With Harari at the helm of the Mossad’s long arm, Israel tried to sabotage Iraq’s budding nuclear program by killing several of its key scientists. But it took an Israeli air raid in 1981 to destroy Iraq’s only nuclear reactor. In this connection, Israel also targeted Gerald Bull, a Canadian scientist who had been developing a super cannon for Iraq. Israel set out to assassinate Iraqi President Saddam Hussein, but cancelled the plan due to a mishap.

Israel’s attempted assassination in 1997 of Khaled Mashal, a top Hamas official, was a failure. Embroiling Israel with Jordan and Canada in a diplomatic row, it marked one of the lowest ebbs in Israeli intelligence history.

With its development of a drone, Israel created what Bergman describes as “a new and particularly deadly method of targeted killing.” Israel deployed this tactic regularly during the second Palestinian uprising. The first Palestinian leader hit by a drone was Hussein Abayat, who had masterminded terrorist attacks in the West Bank and Jerusalem. Sheikh Ahmed Yassin, Hamas’ spiritual leader, was fatally struck by a drone, too.

Israel used the latest technology to assassinate Yahya (The Engineer) Ayyash, whose bombs killed and maimed numerous Israelis. Israel’s assassination of Fathi Shaqaqi, the Islamic Jihad leader, was certainly regarded as a feather in the Mossad’s hat.

Bergman deals with Israel’s war with Hezbollah at length. He cites an Israeli air raid that killed 50 of its trainees, some the sons of senior Hezbollah officials. And he delves into Israel’s assassination of Hezbollah’s elusive military chief, Imad Mughniyeh, who was blown up in Damascus in 2008 in a joint Israeli-U.S. operation.

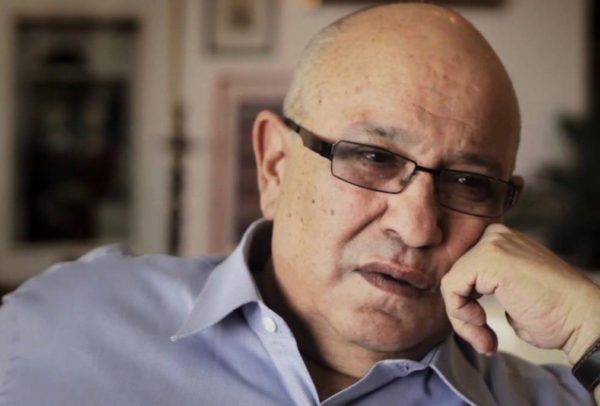

In the past few years, Israeli surrogates from the Kurdish, Baluchi and Azerbaijani communities have assassinated a string of Iranian scientists in Tehran, he says. These operations were supervised by one of the most innovative directors of the Mossad, Meir Dagan. He, too, was behind the assassination of Syrian general Mohammad Suleiman, Syria’s liaison to Hezbollah. He was killed by Israeli snipers at his seaside weekend retreat near the port city of Tartus.

Israel’s targeted assassinations have doubtlessly saved Israeli lives. Its counter-terrorism efforts, encompassing case officers, system analysts, troops in the field, drone operators, interpreters, explosive experts and sharpshooters, have been successful to a very large degree. But Bergman claims they have further “marginalized and delegitimized Israel in the eyes of the world.”

In this respect, he mentions Dagan. No bleeding heart liberal, Dagan came to the firm conclusion that only a two-state solution could end Israel’s conflict with the Palestinians. Counter-violence, after all, has its limitations. But the Palestinians are not Israel’s only adversary. Which is why it continues to be reliant on counter-terrorism operations.