Derek Black, the great white hope of the neo-Nazi movement in the United States, disavowed his beliefs in 2013, transformed himself and disappeared from view.

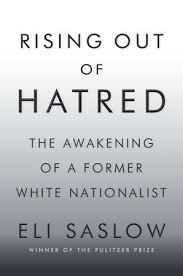

Eli Saslow, a Washington Post reporter who wondered what had happened, tracked him down and interviewed Black and his family and friends. Saslow’s compelling book, Rising Out of Hatred: The Awakening of a Former White Nationalist (Doubleday), skillfully recreates Black’s emotionally and intellectually difficult journey from hatemonger to humanist.

As Saslow succinctly describes Black, he had once been “the rightful heir” to America’s white nationalist movement, the son of Don Black, the founder of Stormfront.org, the largest racist website on the internet, and Chloe Black, who had been married to David Duke, a former Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan.

Duke, Black’s godfather and mentor, sometimes referred to him as “the heir.” The host of an online radio show whose overarching objective was to normalize white nationalist ideas, Black was a prodigy within the movement and a product of it. Thoughtful and polite, he never used racist slurs and opposed violence. But he was unwavering in his core convictions and believed that the United States should be a whites-only nation and that all minorities, including Jews, should be forced to leave.

As he never tired of explaining, he was not prejudiced against minorities, but simply “trying to protect and preserve” the rights of white Christians from “inevitable genocide by mass immigration and forced assimilation.” Europeans like himself had a right to exist and would “not be replaced in our own country.”

Behind his mild exterior lurked a sinister mindset driven by notions of racial superiority. Black theorized about “the criminal nature of blacks” and argued that the natural intelligence of African Americans and Hispanics was inferior to whites.

As for Jews, Black held that they were an insidious enemy capable of subverting the white race by promoting multiculturalism, lenient immigration policies and wars to protect Israel’s interests in the Middle East. As far as he was concerned, Jews were not whites.

In the summer of 2010, Black, a resident of West Palm Beach, Florida, was accepted by New College, one of the best liberal arts colleges in the state. He planned to major in German and medieval history. One day, as he played his acoustic guitar in one of its courtyards, a student named Matthew Stevenson sat down to listen. Stevenson was the only Orthodox Jew on campus, a baptized Presbyterian who had been drawn to the teachings of the Kabbalah and had converted to Judaism. Despite Black’s aversion toward Jews, he liked Stevenson, appreciating, in particular, his sarcastic sense of humor.

Black also made the acquaintance of Rose, whose surname Saslow leaves out. Smart and kind, she hailed from Arkansas’ Baptist Bible Belt. She, too, was Jewish.

Since Black had never had Jewish friends, he remained tense and circumspect about his own background. “Every day he waited to be unmasked, the tension exploding within him in waves of anxiety and guilt,” Saslow writes.

Once his cover was blown, Rose could not reconcile the person she knew and liked with the infamous online racist, and asked for clarification. For the first time, he would have to explain his ideology to an outsider. He told Rose he wasn’t a white supremacist but rather a white nationalist who thought whites would be better off in a separate homeland.

Repelled by his views, she shunned Black.

Stevenson, however, maintained his friendship with Black and continued to invite him to Shabbat dinners in the hope of educating him.

Eventually, Black began to question his assumptions and beliefs, says Saslow. By the autumn of 2012, he had begun to change, his father having noticed he had all but stopped logging on to Stormfront or leaving postings on its message board.

By then, he had fallen for Allison, a fellow student whose views differed sharply from his own. He told Allison — whose surname Saslow also omits — that he respected all people and, due to his relationship with Stevenson, had begun to like and accept Jews. She respected Black and cared about him, but was not ready to publicly date him. Their friendship gradually evolved into a romantic liaison, though Stormfront posters nauseated her.

Although he still considered himself a white nationalist, Black no longer bought into white nationalist rhetoric and myths about “Jewish manipulation,” “testosterone-fuelled black aggression” or larger brain sizes for whites, and now rejected “unfair treatment” against anyone.

Privately disavowing his parents’ ideas, he dropped out of the white racist movement, logging out of his Storefront account for good, turning down invitations to speak at white power conferences and giving up his radio show. During this turbulent period, he enrolled at Western Michigan University’s medieval studies program.

Allison urged him to publicly renounce his former beliefs. Racist ideas now filled him with shame and regret, but he was not yet ready to officially break with white nationalists.

Finally, in a turning point, he sent a letter to a civil rights group his father had always defamed. “The things I have said, as well as my actions, have been harmful to people of color, people of Jewish descent and all others affected,” he wrote. “I will not contribute to any cause that perpetuates this harm in the future.”

And he added, “I can’t support a movement that tells me I can’t be a friend to whomever I wish, or that other people’s races require me to think about them in a certain way or be suspicious of their advancements. Minorities must have the ability to rise to positions of power …”

As Saslow notes, Black’s parents were shocked and appalled by their son’s conversion and assumed he had been afflicted by a mental disorder. They broke with him, but eventually resumed contact.

Black’s challenge was to completely uproot the racist ideology that remained hardwired in every pore of his subconscious. As he confided to Allison, “Sometimes I have this feeling of total societal alienation. I grew up in America, but I was outside it. American culture is like a second language I’m still trying to learn.”

As he left his old persona behind, he issued apologies to people he had offended, caught up with Hollywood movies he had previously despised and boycotted, bought a subscription to The New York Times and began studying Arabic and Islam.

In addition, he acquired an MA degree from Western Michigan, started a PhD program at the University of Chicago, moved in with Allison and altered his name to Roland Derek Black. And then, in a final break with the white nationalist movement, he wrote an op-ed piece for The New York Times entitled Why I Left White Nationalism.

He had come full circle. Rising Out of Hatred cogently documents his amazing transformation from creep to mensch.