The demise of Libyan dictator Moammar Gadhafi in 2011 has led to Islamic militias fighting for control of the country.

The overthrow of Iraq’s Saddam Hussein in 2003 has seen the country collapse, as a full-scale insurgency by Sunni Islamists has been mounted against the Shi’ite government in Baghdad.

In Syria, a weakened Bashar al-Assad’s regime is now one combatant in a Sunni-Shi’ite civil war that has resulted in the deaths of about 170,000 people.

There are some unfortunate places in the world, such as these three, that seem to oscillate between being “rogue” and “failed” states. A lack of genuine consensus on the very nature of the country, and the consequent inability to compromise politically, makes the development of democratic political systems very difficult.

In these states, very deep divisions of clan, tribe or religious sect were temporarily papered over by artificial and enforced attempts at unity, either by a “strongman” who invents his own crackpot political creed, or by an ideologically-based political party that tries to transcend the profound fissures in the polity.

Once the facade of a united country cracks, the polity quickly dissolves into militant factions at war with each other.

Given these horrors, much conventional wisdom has it that such countries become vacuums that breed terrorist movements of one sort or another and as such become dangers to the international order. Afghanistan and Somalia are usually cited as a warning, since both, following their collapse, gave rise to the Taliban and al-Shabaab.

But are failed states necessarily more of a danger than rogue states? It may be true of Afghanistan, which was always a very weak entity, but not of the others. After all, as rogue states, they did an immense amount of damage, both to their own citizens and in foreign adventures.

Somalia collapsed 23 years ago, so many people forget that under the military dictator Mohamed Siad Barre, it was an aggressive irredentist state engaged in trying to bring all Somalis in the Horn of Africa under its rule. Siad Barre advocated the concept of a greater Somalia and fomented violence in Djibouti and Kenya.

In 1977, he launched a full-scale invasion of Ethiopia. In the war, which Somalia lost, each side lost over 6,000 killed. As well, Siad Barre’s final overthrow in the early 1990s cost the country 50,000 killed in internal fighting.

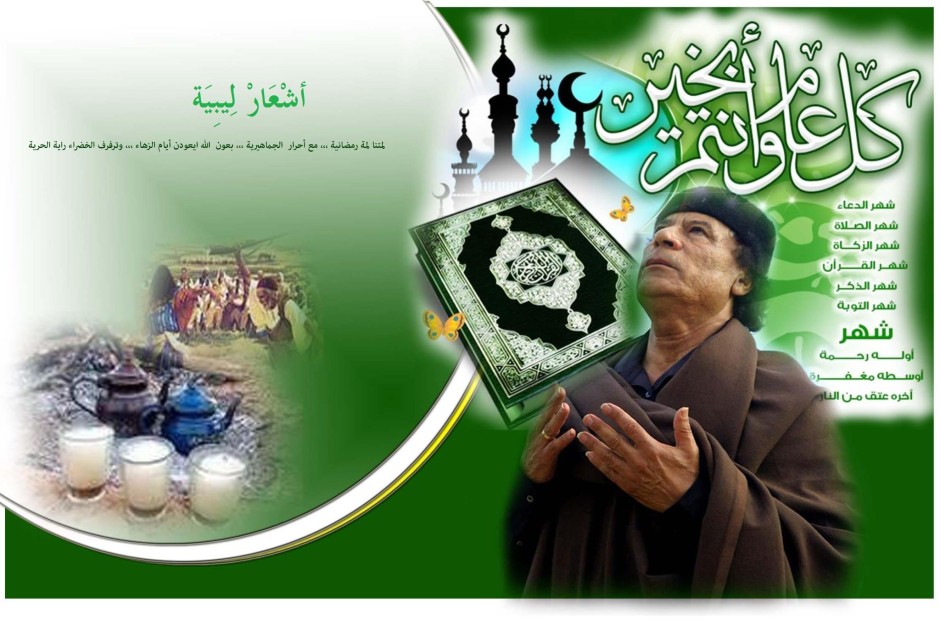

In Libya, Gadhafi, who gained control in a 1969 coup, crafted his own belief system, the so-called “Third Universal Theory,” outlined in his Green Book, which was required reading for all Libyans.

A mixture of utopian socialism, Arab nationalism and the Third World revolutionary ideology, it purported to solve the problems inherent in both capitalism and communism and bring genuine democracy to the Libyan people.

In reality, of course, Gadhafi ran a repressive police state. He also engaged in mischief throughout Africa, arming and bankrolling various terrorist groups in countries such as Chad; even the Irish Republican Army benefitted from his largesse.

He was also responsible for the downing of flight Pan Am 103 over Lockerbie, Scotland in December 1988. It was destroyed by a terrorist bomb, killing all 259 people on board.

Iraq and Syria were both ostensibly governed by wings of the Ba’ath Party. Founded in the 1940s, it espoused pan-Arab nationalism, socialism and anti-imperialism. This too was an attempt to overcome the myriad divisions of ethnicity and religion in the Arab world.

By the time Saddam Hussein gained power in Iraq in 1979, though, the party was a vehicle for a Sunni military dictatorship that held the country in an iron grip. Saddam’s secret police murdered dissidents by the thousands, and unleashed incredible violence against Kurds and Shi’ites.

In 1987-88 alone, the al-Anfal campaign in the north included the widespread use of chemical weapons; in one town, Halabja, a chemical attack killed between 3,200 and 5,000 people. Dozens of Kurdish villages were destroyed, and at least 50,000 people were murdered.

Saddam was also a menace to Iraq’s neighbours. In 1980 he invaded Iran, precipitating an eight-year war in which as many as one million people were slaughtered. Saddam also conquered Kuwait in 1990, and was only ousted after a major coalition defeated him in 1991.

The Assads have governed Syria since 1970, when Hafez al-Assad seized power and made himself head of the Syrian branch of the Ba’ath. He died in 2000, succeeded by his son Bashar.

Here too ideology was a veneer for ruthless authoritarianism. In 1982, the elder Assad quelled an uprising in Hama led by the Muslim Brotherhood, in which upwards of 40,000 people were massacred and much of the city destroyed.

Syria also gained virtual control over Lebanon in the years 1976-2005 and murdered many political opponents there. Following the alleged involvement of Syria in the assassination of the former Lebanese premier Rafik Hariri in 2005, Syria was finally forced to withdraw. Damascus also sought at times to destabilize Jordan.

Therefore, horrific as things are internally in these countries today, they are at least less of an external threat than they once were.

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.