I understand Robert D. Kaplan’s fascination with Romania.

A Balkan nation which experienced the extremes of both fascism and communism within one generation, Romania was forged on the anvils of the Byzantine, Ottoman, Habsburg and Russian empires. Today, it has reverted back to what it was hundreds of years ago — a frontier state of the West facing the East.

Romania’s tangled, convoluted and turbulent past is certainly compelling. And its complicity in the Holocaust remains deeply disturbing.

Kaplan, an American journalist and author with a special interest in foreign affairs, distills his encyclopedic knowledge of this southern European country in a wide-ranging book, In Europe’s Shadow, published by Random House. His penetrating observations of Romania — a fusion of the Latin West and the Greek East — unfold through a bracing blend of memoir, travelogue, journalism and history.

As Kaplan suggests in the prologue, he discovered Romania by way of travel and reading. In the summer of 1973, when the Cold War still divided East from West like a cordon sanitaire, he spent three months travelling in Communist Europe, of which Romania was an integral component. Eight years later, while living in Israel, he wandered into a bookshop in western Jerusalem and stumbled upon a copy of The Governments of Communist East Europe by H. Gordon Skilling, a scholar at the University of Toronto.

Kaplan, then 29, was at a crossroads. “My life at that moment was directionless,” he writes.

Having dabbled in freelance journalism before enlisting in the Israeli army, he decided to return to the writing game after his demobilization. With Skilling on his brain, he bought an airplane ticket to Romania, which, though just as historically and culturally interesting as Israel, was hardly considered a newsworthy destination.

Having landed in Romania, Kaplan knew he had entered a different realm. “The moment I left the plane at Bucharest’s Otopeni airport, I exchanged a world of loud, intense colors in the sun-blinded Middle East for one of a black-and-white engraving in the shivery, November-hued Balkans.”

From that juncture forward, he transformed himself. “I had suddenly gone from being a nobody in a crowded journalistic field in Jerusalem to a person with more status, simply by showing up in this Cold War backwater.” As he admits, he gradually learned how to be a journalist in Bucharest.

To Kaplan, Communism in Romania appeared “like something out of a grainy, nightmarish past, an industrial form of feudalism.” Using the template of Romania’s first Communist leader, Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej, Nicolae Ceausescu, his successor, imposed his diktat on Romania. It would be a nation “Stalinist in ideology, totalitarian in its levels of repression and nationalist in its appeal to the emotions of the people,” Kaplan notes.

To a Westerner like him, Bucharest was a grim city of bread and fuel lines, few cars, silence in the streets and people dressed in the same shapeless coats and furry hats. In short, it was somber and suffocating, just as I had found it when I visited Bucharest in 1991 on a press junket. When I was there, only two years had elapsed since Ceausescu had been deposed and executed, along with his wife, Elena.

By then, Romania had been shaken to its core by waves of instability. Occupied by Austro-Hungarian and German armies in World War I, it was territorially eviscerated by the Soviet Union and Germany in World War II. The Red Army recaptured Bessarabia and northern Bukovina, while the Wehrmacht seized northern Transylvania and handed it over to its ally, Hungary.

Long before these events, Byzantium provided Romania with a cultural and religious identity that has endowed it with “stores of spiritual beauty and aesthetic abundance,” he says.

The expansionist Ottoman Empire periodically invaded Romanian provinces like Wallachia and Moldavia and installed ethnic Greek Phanariots to administer them. But the Romanians avoided the Islamization to which the South Slavs submitted.

Communism in Romania was hardly pre-ordained. Through the 1930s, Romania — a predominantly agricultural country — lacked a substantial indigenous working class, and judging by the tone of its intellectuals, the right exerted greater influence on Romanian society than the left. But being cursed by geography, Romania had to learn to deal with its rapacious next-door neighbor, imperial Russia and its successor state, the Soviet Union. From 1711 onward, as he says, greater Romania was partially occupied by Russia ten times. “For Russia, Romania was on the pathway southward via the Lower Danube and the Black Sea to the Mediterranean …” And yet, he adds, Russia was the protector of Orthodox Christians like the Romanians.

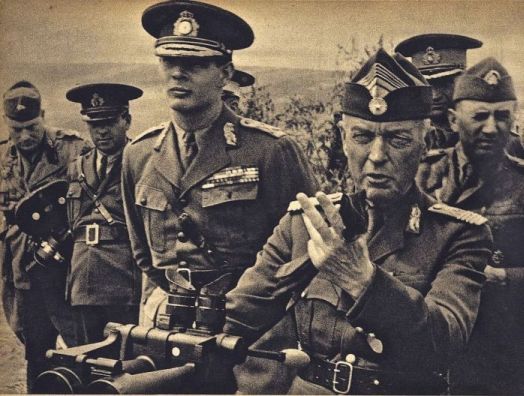

One of the darkest periods in Romania’s history occurred during World War II, when it was under the sway of the authoritarian general Ion Antonescu. Kaplan’s survey of this brutal era is concise yet comprehensive.

Cultivating a close relationship with Adolf Hitler, Antonescu maneuvered Romania into Germany’s closest ally after Italy. Romania contributed 585,000 troops to Operation Barbarossa, Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union, and supplied Germany with oil from its Ploiesti fields. “Antonescu made the cold calculation that an alliance with Germany was simply the best option for regaining territories that Romania had lost to the Soviet Union,” says Kaplan.

Antonescu tolerated the wildly fascist Iron Guard movement in his government for the first five months of his rule, but in January 1941, he decimated it. The Iron Guard, founded by Corneliu Zelea Codreanu (1899-1938), was fiercely antisemitic.

But Antonescu was no less anti-Jewish, having compared Jews to a “disease” and “parasites.” Kaplan describes Antonescu as one of the 20th century’s “great ethnic cleansers,” a man who spoke about the needs to “purify” and “homogenize” Romania and rid itself of “Yids,” “Slavs” and “Roma.”

As Kaplan explains, Jews — the only significant minority in Romania from the 19th century onward — didn’t fit into its racially-based, rural-inspired nationalism. Jews, though a mercantile minority, were nonetheless regarded as Bolshevik sympathizers. In other words, Jews represented the evils of capitalism and Communism simultaneously. The Romanian elite, ranging from King Carol II to politicians like Octavian Goga and A. C. Cuza, were keen antisemites. Yet there were intellectuals who were friendly to Jews, says Kaplan, citing figures such as Lucian Blaga and Mihai Ralea.

Given the deep reservoir of antisemitism in Romania and its wartime dalliance with Nazi Germany, Romanian Jews were at great peril after the war erupted. Antonescu adopted what amounted to an extermination policy toward the large Jewish community. Through deliberate starvation and mass butchery, he orchestrated the murder of up to 300,000 Jews in Bessarabia, northern Bukovina and Transdniestra — areas the Romanian army retook from the Soviet Union in the first weeks of the war. But in Romania proper — Wallachia, Moldavia and southern Transylvania — Antonescu spared upwards of 375,000 Jews holding Romanian citizenship.

Drawing on the work of Romanian specialist Larry Watts, Kaplan says, “The survival rate of the Jewish population under his direct civil, administrative and military control — within the legal borders of Romania, that is — was greater than that of any other Axis ally, protectorate or occupied area aside from Finland.” But in a caveat, he adds, “If you were a Jew in the areas that Antonescu’s troops recaptured from the Soviet Union, there were few places worse to be during that period.”

By Kaplan’s reckoning, Antonescu took a relatively lenient attitude toward Jews in Romania proper only after being convinced Germany might lose the war. But in 1941, when Germany was on the ascendancy, he allowed the massacre of about 13,000 Jews in the city of Jassy.

“Antonescu was more of a realist than a fanatical fascist, and so he was always sensitive to shifting geopolitical winds,” says Kaplan. But as he suggests, Antonescu was restrained by internal considerations as well. His harsh anti-Jewish policies were opposed by some Romanian intellectuals, the queen mother, Helen, and the leader of the National Peasant Party, Iuliu Maniu. “Again, this all must been seen in the context of Soviet and American victories on the battlefront,” he states.

For decades after the Holocaust, Romania refused to acknowledge its role in the atrocities, but in 2003, while serving a third term as president, Ceausescu’s successor, Ion Iliescu, publicly admitted Romania’s guilt in the mass murder of Jews.

As Kaplan says, Antonescu was not the only Romanian leader who was partial to ethnic cleansing. Ceausescu, by allowing Jews to emigrate in exchange for a head tax, achieved a degree of racial purity in Romania that his fascist predecessors doubtless would have hailed. Ceausecsu applied the same principle to ethnic Germans who wished to leave.

In closing, Kaplan warns that Romania, as a minor power, must always be cognizant of shifts in the international and European strategic balance. As he puts it, “If Germany and the powers within the European Union cannot stand up to a revanchist Russia, if the EU crumbles from within, Romania … will be in trouble, since the United States is not likely to provide quite the same level of support to its allies as it did during the Cold War. The West will be far away, Russia in whatever form will be close …”

As in centuries past, Romania must navigate through treacherous shoals to maintain its freedom, independence and sovereignty.