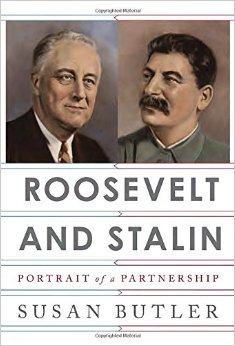

Susan Butler’s wide-ranging, comprehensive account of a pivotal wartime alliance, Roosevelt And Stalin: Portrait of a Partnership (Alfred A. Knopf), bores into U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s political relationship with Soviet leader Joseph Stalin. They were certainly an odd couple, hailing from radically different backgrounds and torn by profound ideological differences, but they respected each other and worked in tandem to defeat the Axis powers and reshape the postwar world.

Butler, an American historian, explains why and how two politically antagonistic nations, the United States and the Soviet Union, cooperated in the quest to smash Germany and Japan, which threatened to dominate the destinies of Europe and Asia.

Mining previously classified archival materials, she brings a fresh perspective to a weighty topic. Butler’s narrative, anchored by thorough research and brightened by lucid prose, is bookended by historic leadership summits in Tehran and Yalta. These meetings enabled Roosevelt, Stalin and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill to map out joint plans for defeating the Axis powers and carving out a new global order.

The pair had been corresponding for more than a year before Stalin finally accepted Roosevelt’s proposal for a face-to-face meeting. Stalin had continually fobbed him off, saying he was unable to leave Moscow due to the German offensive into the Soviet Union. But after the Red Army recaptured two-thirds of the territory the Wehrmacht had seized, Stalin told Roosevelt he was ready to talk.

The venue they settled on, Iran, had been jointly occupied by the Soviet Union and Britain over fears of Germany’s intentions in this oil-rich Muslim country. After invading Iran, they forced the pro-German Iranian ruler, Shah Reza, to abdicate and installed his 21-year-old son, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, on the throne. Iran was also important because it was a conduit for the shipment of U.S. military aid to the Soviet Union.

According to Butler, Roosevelt and Stalin had mutual interests.

Roosevelt, whose diplomatic recognition of the Soviet Union in 1933 had aroused the ire of old school anti-communists in the State Department, counted on Moscow’s support to establish a more effective version of the League of Nations. And he required Moscow’s cooperation to redraw Europe’s borders.

Stalin’s predecessor, Vladimir Lenin, had sought the friendship of the United States to shield the newly-created Soviet Union from European aggression. And following Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, Stalin was dependent on U.S. war materiel to help him turn the tide of the war.

As Butler points out, Roosevelt and Stalin were both highly intelligent and sociable. When they finally met in Tehran in November 1943, they discussed a plethora of issues, from Poland’s future frontiers to the postwar containment of Germany.

Much to Europe’s astonishment, Germany and the Soviet Union had signed a non-aggression pact on the eve of World War II. Stalin, seeking a mutual defence agreement with Britain and France, had dispatching his foreign minister, Maxim Litvinov, to iron out the details. But having been spurned by London and Paris, Stalin moved to expand trade ties with Germany and open negotiations with Adolf Hitler’s Nazi regime. To appease Berlin, Stalin fired Litvinov, a Jew, and replaced him with Vyacheslav Molotov, his closest companion.

Roosevelt tried to dissuade Stalin from getting into bed with Hitler, but Stalin rejected the overture, believing that a marriage of convenience with Hitler would give him more time to prepare for an eventual German attack on the Soviet Union. In Stalin’s view, Hitler would honor their pact through 1941.

On the eve of Germany’s thrust into the Soviet Union, known as Operation Barbarossa, American and British diplomats warned Moscow of the impending invasion. On the recommendation of his generals, Stalin called up 800,000 reservists five months before the eruption of the war. But as late as June 15, 1941, a week before Germany’s massive onslaught, Stalin was convinced that Hitler would not attack. “Hitler is not such an idiot,” he claimed in a gross miscalculation.

With German forces fast advancing into the Soviet Union in the summer of that fateful year, Roosevelt decided to help Stalin, realizing that Hitler’s dream of creating a Pax Germanica in Europe would threaten U.S. interests. There was strong resistance in the United States to assisting Moscow, but Roosevelt remained undeterred.

Under the Lend Lease program, Washington agreed to send the Soviet Union monthly shipments of 400 planes, 500 tanks, 5,000 cars, 10,000 trucks, huge quantities of anti-tank and anti-aircraft guns, motorcycles, field telephones, radios, as well as food stuffs.

“There was a problem,” Butler writes. “The American embassy and military staff were largely hostile to Soviet survival. Most of them — career diplomats and military personnel alike — deeply mistrusted the Soviet leaders and tried to subvert FDR’s all-out aid effort.”

This anti-Soviet clique was sidelined, but Stalin wanted more than guns and butter. He demanded a second front in Europe to relieve pressure on the Red Army. Instead, Roosevelt ordered an invasion of French North Africa in 1942. Sixty five thousand troops, roughly half American and half British, participated in the operation. Although it marked the first time the U.S. army had engaged Germany in combat, Stalin was not entirely satisfied, having urged the allies to open a European front.

In appreciation of U.S. efforts, Stalin loosened religious restrictions, condoning churchgoing and reinstating Russian Orthodox metropolitans.

Stalin, in a diplomatic coup, had signed a non-aggression accord with Japan in April 1939. But now, he considered Japan an enemy and was eager to retake land Japan had wrested from Russia in the 1904/1905 war. Talks with the United States on this issue commenced after the Joint Chiefs of Staff informed Roosevelt that Soviet participation in a war against Japan would be an absolute necessity by way of reducing U.S. casualties.

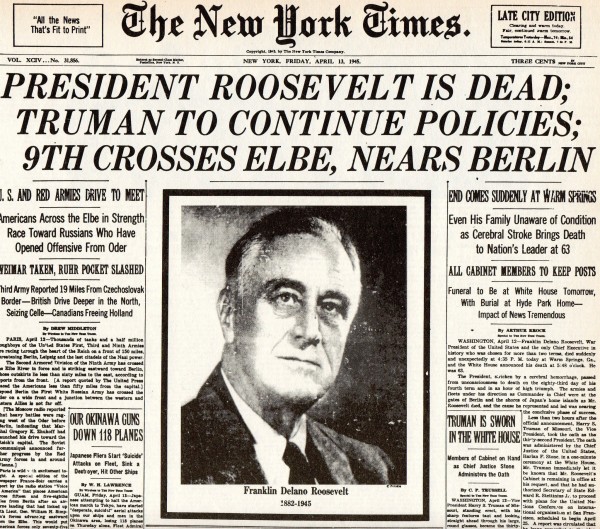

As Butler observes, Stalin was shocked by Roosevelt’s death in April 1945. Avrell Harriman, the U.S. ambassador in Moscow, reported that Stalin was “deeply shaken and more disturbed than I had ever seen him.”

At Stalin’s order, the Soviet Union went into official mourning for a U.S. president Izvestia described in glowing terms. Stalin, in a letter to Roosevelt’s successor, Harry Truman, described him as “the greatest politician on an international scale and a spokesman for peace and security after the war.”

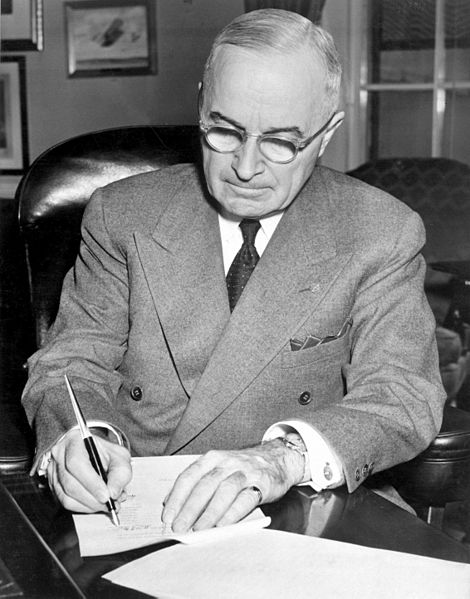

Stalin clearly sought a cooperative arrangement with the United States, and while Truman was determined to honor Roosevelt’s policies, he was wary of Stalin, comparing him to Hitler. As for Stalin, he lacked respect for Truman, Butler notes.

Mistrust crept into Washington’s entente with Moscow in the summer of that year. In accordance with Stalin’s promise, one million Soviet troops invaded Japanese-held Manchuria. But on that day, August 9, the United States dropped an atomic bomb on Nagasaki. “To everyone in the Soviet Union, the bomb was a stunning blow,” says Butler. “The timing made it look to them like a deliberate effort to rob the Soviets’ entry into the (Pacific) war of any significance…”

When Truman refused to grant the Soviet Union a badly needed loan, or share nuclear secrets with Moscow, the die was cast for further misunderstandings. Anthony Eden, the British foreign secretary, put it succinctly: “Had Roosevelt lived, he would never have permitted the present situation to develop. His death, therefore, was a calamity of immeasurable proportions.”

What had been a mutually beneficial relationship collapsed in a welter of acrimony as the Cold War, pitting the United States against the Soviet Union, intensified.

Butler tells this complex story with authority and elan.