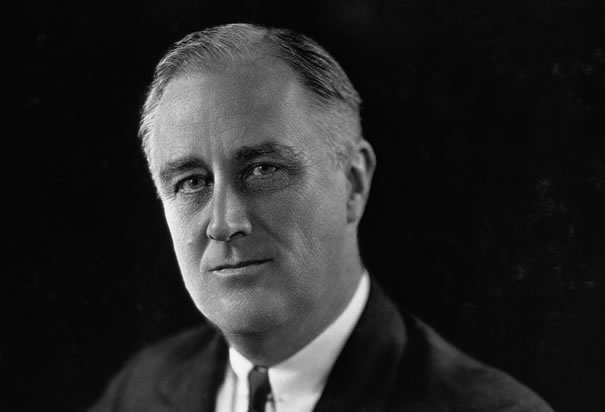

Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal administration coincided with the emergence of state-sponsored antisemitism in Germany and the mass murder of Jews during the Holocaust. How did Roosevelt respond to these shattering events? Ambivalently, conclude American University historians Richard Breitman and Allan Lichtman in their important and cogent book, FDR and the Jews, published by Harvard University Press.

“For most of his presidency, Roosevelt did little to aid the imperilled Jews of Germany and Europe,” they write. “He put other policy priorities well ahead of saving Jews and deferred to fears of an antisemitic backlash at home.”

When he addressed Jewish issues, he did so behind the scenes, and when he hesitated, he allowed the U.S. State Department, which was less than sympathetic to Jews, to call the shots.

Nonetheless, they point out, Roosevelt did more for Jews than any other world leader, even if his efforts seem deficient by today’s standards.

According to Breitman and Lichtman, Roosevelt went through four different phases with respect to Jewish issues.

During his first term, he was a bystander to the Nazi persecution of Jews, refusing even to meet American Jewish leaders. After his reelection, he was stirred into action, loosening immigration restrictions and promoting plans to resettle endangered Jews in other countries.

As World War II approached, he shunted aside concerns for Jews to concentrate on internal security and foreign affairs, fearing that an undue emphasis on the Jewish question would embolden his isolationist adversaries and affect his maneuverability in managing international relations.

During the last phase, starting in 1943, Roosevelt shifted course, taking concrete measures to assist Jews in Nazi-occupied Europe and denouncing organized antisemitism.

On a personal level, Roosevelt was well-disposed toward Jews. As governor of New York state, with the largest concentration of Jews in the United States, he denounced antisemitism, became the first presidential candidate to criticize anti-Jewish prejudice and backed Palestine as a Jewish homeland.

Once he was president, he drew upon Jewish talent to pursue his agenda. During his unprecedented four terms, 15 percent of his appointees to federal government and White House positions were Jews, far exceeding the Jewish percentage of the population. And one of his key cabinet members, Henry Morgenthau Jr., secretary of the treasury, was Jewish.

Lest it be forgotten, Roosevelt took office in an era when antisemitism was a fairly widespread phenomenon, with nearly half of Americans claiming that Jews exercised too much influence on the country. By 1941, one/third of the citizenry was of the view that Jews were trying to force the United States into war.

Charles Lindbergh, the American hero, levelled that vile accusation almost three months before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor prompted the United States to enter the war. In formulating his policies, Roosevelt took such sentiments into account.

And, as the authors note, he was also constrained by rising isolationism, which held that the United States should mind its own business and not entangle itself in foreign political and military affairs. Since Roosevelt required the support of isolationists like U.S. senators Burton Wheeler of Montana and Hiram Johnson of California to pass his program of domestic reforms, he had to tread carefully, notwithstanding the fact that his most loyal supporters were Jews.

Shortly after his accession to the presidency, Roosevelt warned Adolf Hitler’s economic advisor, Hjalmar Schacht, that Nazi antisemitism threatened American-German relations. But high officials in the U.S. State Department, being committed to a policy of non-intervention in the internal politics of foreign powers, discouraged all protests and boycotts against Germany.

Breitman and Lichtman single out Breckinridge Long, an assistant secretary of state for special war problems, as one of those officials who blocked initiatives to help Jews.

Xenophobic and prejudiced, Long was an antisemitic patrician who played a role in the State Department`s decision to tighten visa controls and sit on a report from the World Jewish Congress that the Nazis were considering a plan to exterminate European Jews.

In deference to ethnocentrism in American society, the Roosevelt administration chose to fill only 20 percent of immigration quota levels from Germany in 1935, this at a time when tens of thousands Jews were clamouring to leave.

For the same reason, Roosevelt supported an offer by the Dominican Republic`s strongman, Rafael Trujillo, to welcome Jewish immigrants. But U.S. diplomats there were hostile to the project, being skeptical of Trujillo`s sincerity and fearful that Germany would send Nazi agents disguised as Jews to that Caribbean island. In the end, only 757 Jewish refugees were resettled in the Jewish colony of Sosua.

Roosevelt did not permit the St. Louis, a German passenger ship filled with German Jews, to dock at a U.S. port. But Breitman and Lichtman credit him with pressuring Cuba and Bolivia to accept upwards of 6,000 and 20,000 Jewish refugees respectively.

Together with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, Roosevelt warned Germany in 1942 that perpetrators of war crimes would be punished after the war. Neither leader, however, offered plans to thwart the Holocaust.

From December 1942 until January of 1944, Roosevelt gradually drifted away from his position that only a military victory could save the victims of Nazi terror. “He came to realize that at least some Jews could be rescued during the war,” they write.

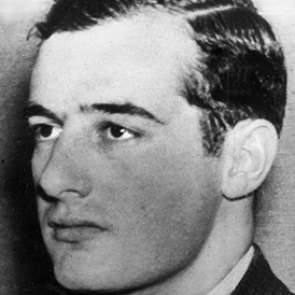

The War Refugee Board, created at the urging of Morgenthau in 1944, performed this function admirably, particularly in Hungary through the good offices of Raoul Wallenberg, a Swedish national. Although it had a small staff and relied on private sources of funding, it saved as many as 200,000 Jews.

The War Refugee Board, though, was unable to persuade the United States and its allies to bomb the gas chambers and crematoria at the Auschwitz death camp and the railway lines leading there.

“Clearly, the U.S. War Department had no interest in devoting resources to a non-military mission for saving Jewish lives,” they observe.

Yet by sending aircraft and tanks to British forces in Egypt and Libya, beleaguered by Germany’s Gen. Erwin Rommel, the United States inadvertently helped save the Jewish community in Palestine, they add.

In conclusion, Breitman and Lichtman deliver a nuanced verdict on Roosevelt’s response to Nazism and the Holocaust.

Due to circumstances beyond his control, such as the worst economic crisis in American history and the prevalence of antisemitism and isolationism in the United States, he was forced to make “difficult and painful trade-offs.”

He did little to assist Jews in Germany, nor did he speak out against Nazi antisemitism. Yet he admitted more than 100,000 Jewish refugees into the United States, cajoled other nations, like Brazil, to accept thousands of Jewish immigrants and openly backed Jewish settlement in Palestine. And, of course, he endorsed the work of the War Refugee Board, the only agency of its kind during the war.