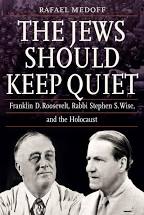

American historian Rafael Medoff has written an impressive and important book about the United States, Nazi Germany and the Holocaust. The Jews Should Keep Quiet: President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Rabbi Stephen S. Wise, and the Holocaust (The Jewish Publication Society) is an unsparing condemnation of a president who was slow to help Jewish refugees and reluctant to criticize Adolf Hitler’s Germany. It is also a stunning critique of an American Jewish community leader who allowed himself to be stifled, manipulated and virtually silenced.

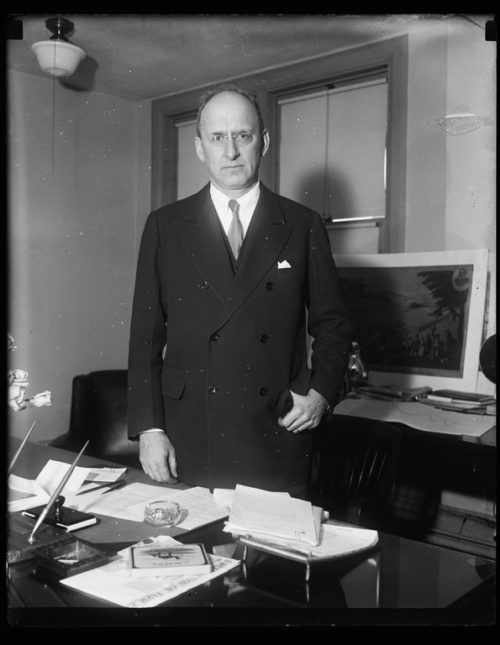

One of the central figures in Medoff’s volume, which is based on recently discovered documents, is Wise, whom he describes as the foremost American Jewish community leader of the 1930s and 1940s. A Reform rabbi and an outspoken Zionist, he was a founder of the American Jewish Congress and the American Civil Liberties Union, a board member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and an activist for labor rights, women’s suffrage and international disarmament.

Wise endorsed Roosevelt for New York governor in 1928, but had a falling out with him in 1931 over his reluctance to take on New York City’s corrupt Tammany Hall political machine. Charging Roosevelt with lacking “deep-seated convictions,” Wise said he was “all clay and no granite.” After Roosevelt became president and began advancing a social justice agenda under the New Deal, Wise warmed up to him. But he was privately concerned about Roosevelt’s silence concerning the plight of German Jews under Nazism, says Medoff, the founding director of the David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies.

Wise, who was born in Hungary, sought U.S. intervention in Germany’s persecution of Jews and the admittance of German Jewish refugees into the United States. Roosevelt appeared sympathetic, but in practice he was largely indifferent, bowing to widespread antisemitism in a society where Jews were not yet fully accepted.

This was an era when half of Americans perceived Jews as greedy and dishonest and one-third believed they had too much power and were overly aggressive, according to polls. Even in the halls of government, a small number of congressmen exhibited fierce xenophobia and even outright antisemitism. One member of the House of Representatives, John Rankin, accused “international Jews” of trying to drag the United States into World War II.

And with the unemployment rate reaching 25 percent in the early 1930s, many Americans feared that new immigrants would “steal” jobs that rightfully belonged to U.S. citizens.

The problem that Wise faced in dealing with the Roosevelt administration was the same one that confronted American Jews. Being avid supporters of Roosevelt’s domestic policies, they were loath to lambaste him, particularly when his spokesmen claimed that rescuing Jews conflicted with the overarching goal of winning the war. They also feared that protests might jeopardize their hard-won place in America. “How to respond to the plight of Europe’s Jews without endangering American Jewry’s own status would prove to be the most difficult challenge of Wise’s life,” writes Medoff.

Given these factors, Wise adopted a middle-of-the-road position in which he privately lobbied for U.S. assistance while protecting Roosevelt and his administration from public Jewish criticism. This policy would remain his priority during this period. “That he was able to sustain his image as an outspoken critic of Hitler, while simultaneously shielding Roosevelt from criticisms over his refusal to verbally confront the Nazi regime, is testament to Wise’s impressive public relations skills,” says Medoff.

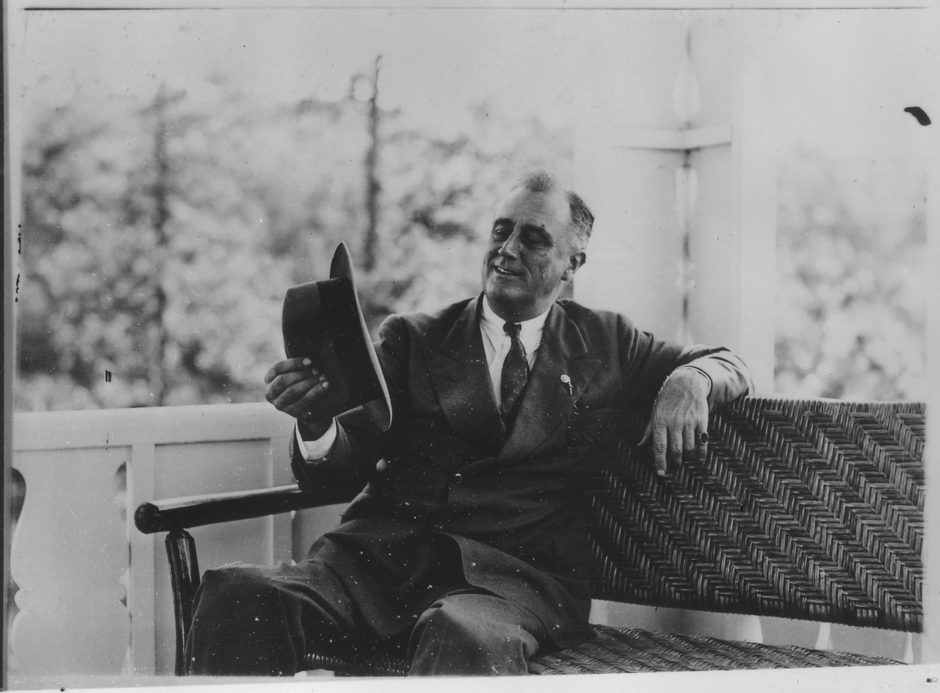

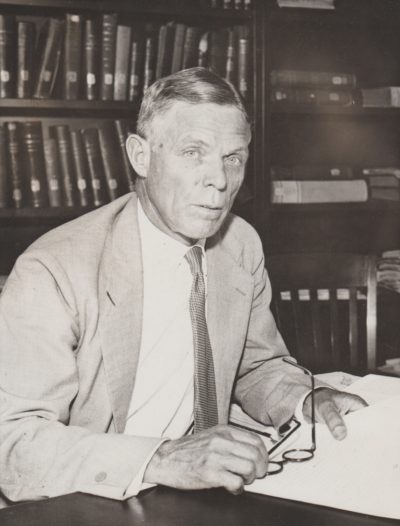

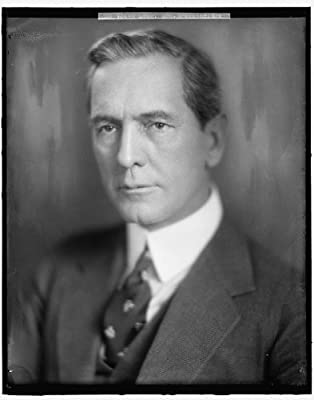

From the moment Hitler assumed power in 1933, Roosevelt tried to avoid entanglement in Germany’s domestic affairs. Having appointed the historian William Dodd as the new U.S. ambassador to Germany, Roosevelt told him that the persecution of German Jews was not “a U.S. government affair.” As Medoff notes, Roosevelt thereby reversed his predecessor’s policy of exerting pressure on Hitler to end his anti-Jewish practices.

Roosevelt, too, informed Secretary of State Cordell Hull that U.S. compliance with the informal anti-Nazi boycott was undesirable because it would damage American trade with Germany and upset some Americans.

To Wise’s growing frustration, Roosevelt refrained from issuing public statements about Germany’s antisemitic policies. In 82 press conferences during 1933, Roosevelt mentioned that topic only once. “Roosevelt was not willing to risk even mildly straining American-German relations by publicly taking issue with Hitler’s human rights abuses,” writes Medoff.

In pursuit of this objective, Roosevelt instructed one of his cabinet ministers, Secretary of Interior Harold Ickes, to remove critical references to Hitler from three of his speeches.

After the 1938 Kristallnacht pogrom in Germany, Roosevelt was conspicuously silent, but he recalled the U.S. ambassador in Berlin, agreed to extend the visitor’s visas of German Jews in the United States, and admitted some Jewish refugees.

Roosevelt’s Jewish advisors, ranging from speechwriter Samuel Rosenman to Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau Jr., generally were unwilling to raise Jewish concerns with their boss. Medoff points out that Roosevelt had his share of antisemitic advisors, including Stephen Early and Edward Flynn, both of whom were longtime friends.

Roosevelt’s de facto appeasement of Germany did not mean he condoned the Nazi regime. Throughout the 1930s, in private conversations and cabinet discussions, he expressed abhorrence of Nazism and regarded Hitler as a clear and present threat to world peace.

Medoff, however, argues that Roosevelt was probably affected by a residue of the social antisemitism that was all too common in his own family and in the upper crust circles he moved. In private, Roosevelt was prone to making “unflattering statements” about Jews, and these comments blended into a pattern of notions signifying that it was undesirable to have too many Jews in any single profession, institution or geographic locale; implying that America should remain an overwhelmingly white, Protestant country, and insinuating that Jews on the whole possessed certain innate and distasteful characteristics.

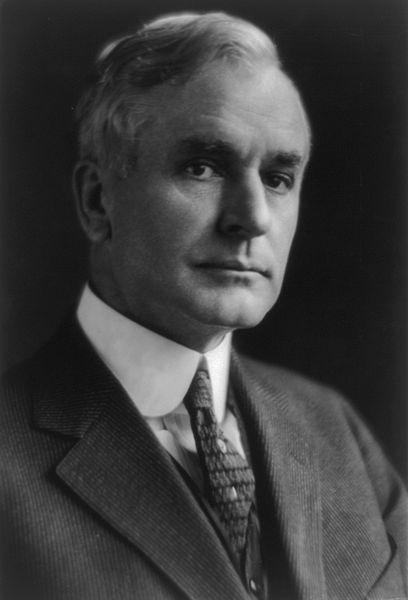

Breckinridge Long, Roosevelt’s friend and donor whom he appointed to a senior position in the State Department, certainly subscribed to these beliefs. Long devised a series of measures to keep Jewish refugees out of the United States. From 1942 until 1945, only 10 percent of the quotas from Axis-controlled European countries were actually used. Nearly 190,000 quota places remained vacant even as Jews clamored to find a safe haven in the United States.

The Roosevelt administration refused to budge from its restrictive immigration policy during the ill-fated 1938 Evian conference on refugees. Wise ascribed “the appalling disappointment of Evian” to Britain rather than the United States. And he continued to stay silent after Washington turned away the St. Louis, a German ship carrying hundreds of German Jewish refugees. Wise’s deafening silence reflected his “profound aversion to saying anything that would embarrass Roosevelt,” says Medoff.

Wise also declined to endorse U.S. Senate legislation to permit refugees to settle in Alaska, fearing it would result in the “harmful impression … that Jews are taking over some part of the country for settlement.” Nor was he willing to ask Roosevelt to issue a warning to Germany that its leaders would be held personally responsible for their crimes against humanity.

Wise’s reticence prompted some Jewish activists, such as Peter Bergson, to lash out at him. In exasperation, Wise unwisely compared him to Hitler.

Wise was shocked when more than 400 rabbis arrived in Washington, D.C. on October 6, 1943 to plead for the creation of a dedicated U.S. agency to rescue Jews in Nazi-occupied Europe. “For Wise and other mainstream Jewish leaders, the spectacle of Jews marching through the streets of the nation’s capital, during wartime, to promote specifically Jewish requests such as rescue, was anathema,” says Medoff.

In 1944, Roosevelt established the War Refugee Board to rescue victims of Nazi oppression, but the government paid for only a fraction of its expenses, leaving the balance of the founding to Jewish organizations like the American Joint Distribution Committee. Nonetheless, the War Refugee Board saved about 200,000 Jews and 20,000 non-Jews.

Wise was almost entirely absent from discussions about a plan for the Allies to bomb the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp in Poland and the rail lines leading to it. While he supported private efforts to advance the proposal, he did not want to draw public attention to the fact that the United States opposed it.

In closing, Medoff suggests that Wise had little wiggle room as he sought to do good. “Regardless of who stood at the helm of the American Jewish community, there was the reality of an unsympathetic White House, an antisemitic State Department, a Congress that was largely anti-immigration, and a public that was strongly isolationist prior to 1941.”

He adds that Roosevelt, a wily operator, took advantage of Wise’s adoration of his policies and leadership “to manipulate Wise through flattery and intermittent access to the White House.”

Medoff leaves a reader with the impression that Wise’s diplomacy was an abject failure.

“By taking upon himself the task of making excuses for Roosevelt and shielding him from Jewish criticism, Wise was in effect implementing what Roosevelt said to him in 1936 about the ‘necessity of Jews lying low.’ He was also helping to facilitate policies that neither he himself, nor most American Jews, supported, from Roosevelt’s pursuit of cordial — sometimes even friendly — relations with Nazi Germany in the 1930s, to his closing of America’s doors to refugees despite unfilled quotes, to his refusal to take even minimal steps to interrupt the mass murder process.

“Roosevelt exploited the insecurities of a mostly immigrant and not yet fully accepted community and outmaneuvered Wise to ensure that Jews would keep quiet.”

Need more be said?