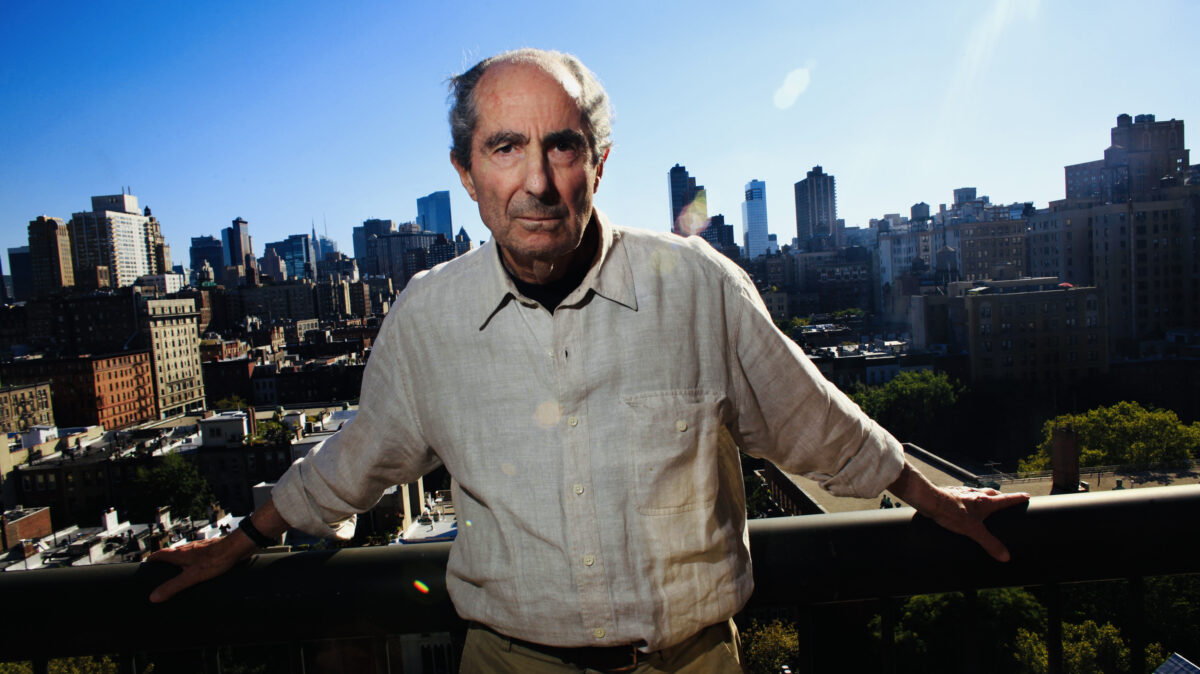

Philip Roth, the great American novelist, was 77 when he agreed to be interviewed for Roth on Roth, a nearly one hour documentary by William Karel and Livia Manera in which he bares his soul. Speaking candidly, he discusses a wide range of issues.

Roth on Roth, currently being screened online by the Toronto Jewish Film Foundation, was released in 2011, seven years before he died.

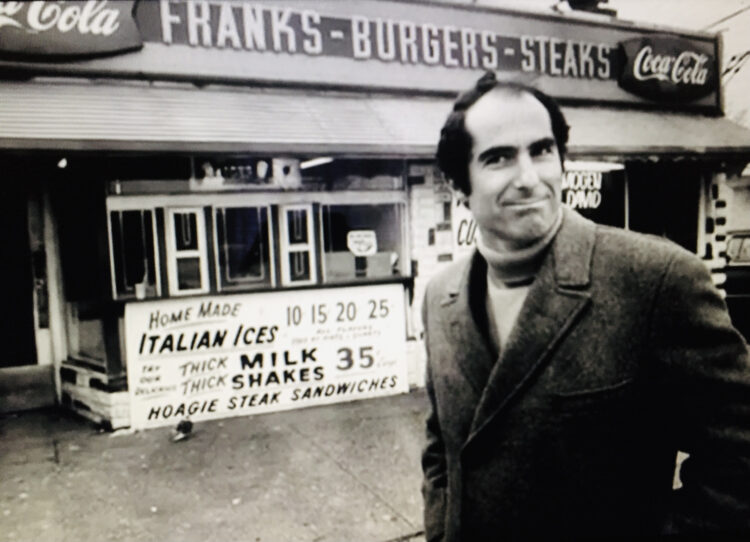

Born in Newark, New Jersey in 1933, Roth was the son of Americanized Jews one generation removed from their East European immigrant roots. As he recalls, his parents were not in the least nostalgic for the “old country.” As he puts it, “I might have heard about it from my grandfather, but he spoke only Yiddish,” a language Roth did not understand.

His father, a salesman, expected him to be a lawyer, but certainly not a writer. Roth is grateful that he never stood in his way, yet he became “a terrific pain in the ass.” He does not elaborate, but admits he left Newark to distance himself from him. “I just wanted to get the hell away.”

Decades later, when Roth was famous, his father came full circle. While on a cruise, he passed out free copies of his son’s latest novel and autographed it with his own name.

From 1962 to 1967, Roth publishing nothing. This bleak phase appears to have coincided with his first “very bad, brutal and lurid” marriage. “I couldn’t write,” he confesses. “I felt like I was drained. I needed to recover my confidence.”

Roth required a psychoanalyst who would listen empathetically to his woes. Thanks to his therapist and conversations with attentive friends, he discovered he had a wonderful talent for dark humor. From this process emerged one of his finest novels, Portnoy’s Complaint, which sold 350,000 copies in the first month alone. “It was a sensation,” he says in an awe-struck tone.

A number of Jewish readers were manifestly upset, not only with the flawed Jewish characters but with the explicit sex. One irate reader went as far as accusing him of being an “enemy of the Jews.”

This was not the first time an accusation of this seriousness had been flung at him. Roth was denounced as a self-hating Jew after the publication of the short story Defender of the Faith and of the novella Goodbye, Columbus.

In his conversation on screen, he does not wish to be seen as an “American Jewish” writer. “I don’t want to write in Jewish,” he explains. “I write in American. I was raised in America. I am an American.”

Portnoy’s Complaint, of course, was a watershed in his career. “Suddenly, I had money,” he gushes. At the age of 36, he could finally afford to buy a house and a car and pay for a trip around the world with his girlfriend, who remains unidentified.

Roth discloses he left New York City after the publication of Portnoy’s Complaint, saying he never felt connected to it. He bought a house in rural Connecticut, where he could ruminate in solitude and where he would compose novels like American Pastoral, Zuckerman Unbound and The Professor of Desire.

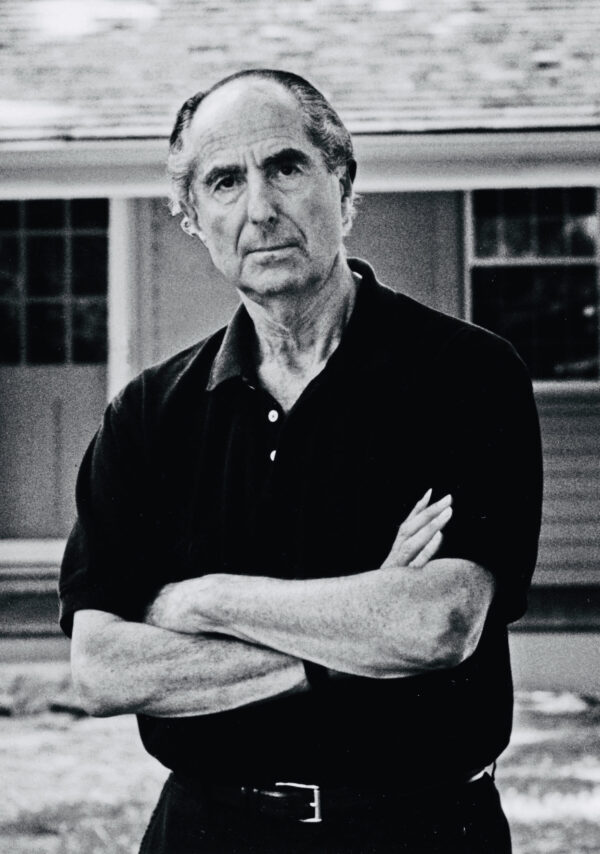

Working seven days a week, he acknowledges he’s “completely lost” when he embarks on a new book. When he’s not writing, he feels depressed and anxious. In effect, he writes himself out of his depressive mood.

Sporadically, he think he’s lost his “magic” and does not have what it takes to produce a novel. Yet he muddles through, inventing characters as he goes along. He concedes there is a “journalistic” side to his craft because novels are built on a foundation of facts, information and “real stuff.”

When he finishes a manuscript, he sends copies to trusted friends to evaluate. One of his friends is the actress Mia Farrow, but it’s unclear whether she’s one of the “judges.”

Plagued by back aches, Roth segues into a somber topic. In his view, many first-class writers have committed suicide. “I don’t want to join that list,” he says emphatically.

The prospect of dying leaves him fearful and sad, but he knows that time is running out. “There’s nothing to be done,” he says in mock despair. “But who cares anyway?”