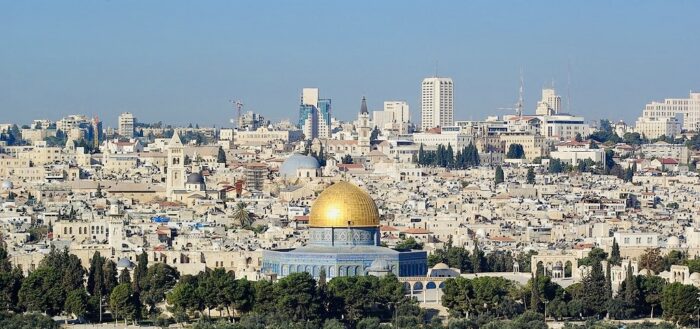

The unification of Jerusalem, Israel’s capital, was one of the defining moments of the Six Day War period.

Until 1967, Jerusalem was divided into western and eastern sectors. Israel controlled the western half. Jordan was in charge of the eastern portion. Israelis were not allowed into East Jerusalem and Arabs were not permitted to visit West Jerusalem. Only foreigners could come and go as they pleased.

That era vanished with Israel’s conquest of East Jerusalem.

The Israeli government was driven by two objectives: to unite and modernize the city, which is holy to Jews, Muslims and Christians, and to ensure that it would remain in Israel’s hands and never be artificially divided again.

The mayor of Jerusalem, Teddy Kollek, worked ceaselessly to achieve these overlapping goals, even if it meant destroying Arab neighborhoods and displacing Palestinians from their homes in East Jerusalem.

This urban renewal process is examined by Danae Elon in Rule of Stone, a thought-provoking documentary to be screened at the Toronto Jewish Film Festival, which runs from June 5-15.

Elon, the daughter of the distinguished Israeli journalist Amos Elon, approaches the topic from a critical point of view. She objects to the injustices that Israel meted out to Palestinians in its quest to amalgamate Jerusalem into a single city under its sole authority. In fleshing out her argument, she interviews Israeli Jews and a sprinkling of Palestinian Arabs.

Moshe Safdie, the Israeli-born Canadian architect who achieved fame as the visionary designer of the Habitat ’67 housing complex during Montreal’s Expo ’67 world fair, is Elon’s main interviewee.

Kollek, intent on converting the derelict area around the old Israel-Jordan border into an architectural showpiece, asked Safdie to redesign it with the proviso that all the buildings would be built with luminescent Jerusalem stone.

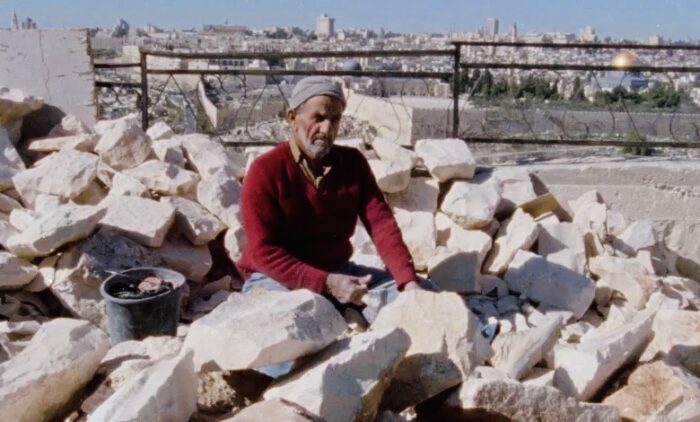

During the Palestine Mandate period, Britain enforced this decree in the knowledge that Jerusalem stone, an organic material meticulously cut from local quarries by seasoned masons, captures the city’s mellow gold and yellow light.

In accordance with this provision, and true to his belief that new buildings should blend in seamlessly with far older structures, Safdie designed the outdoor Mamilla mall, a collection of high-end shops, restaurants and cafes.

Before construction commenced, the shabby Arab neighborhood that stood there was torn down. Safdie appears to have no regrets about its demolition, saying it was “basically a slum.”

Gilo, a Jewish neighborhood which arose after the war, was also built on land that had been inhabited by Palestinians. Its residents were forced to tear down their homes in compliance with an Israeli order.

In retrospect, Safdie admits he is not sure whether he would have participated in such projects if he had to do it all over again.

As Elon points out, the new Jewish neighborhoods in East Jerusalem were built with the express purpose of preserving the 70/30 Jewish-Arab population ratio. Safdie says that Palestinians found it difficult to obtain construction permits under this restrictive system.

Zvi Efrat, a Jewish architect who disagrees with this discriminatory policy, believes that Israeli architects did not dwell on the politics of the Arab-Israeli conflict when they accepted a commission to design a building in East Jerusalem.

Another Jewish architect, Elinoar Barzacchi, reminds Elon that architects are merely the “executioners” of Israeli government policy.

Elon, who was born and raised in Jerusalem, has the last word.

Contemplating the magnificent allure of Jerusalem stone, she muses that the buildings clad with it conceal a complicated and cruel reality.