In one of its biggest gambles in decades, Russia has plunged headlong into the raging civil war in Syria. The price it is paying for its armed intervention is already staggering and may yet grow worse.

On September 30, the Russian Air Force began bombing rebel strongholds in western Syria, its planes taking off from a base in Latakia in support of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s embattled Baathist regime. Few of its raids were aimed at Islamic State, the Sunni jihadist organization which has seized vast swaths of territory in Syria and probably poses the greatest threat to Assad.

A few days later, in a theatrical show of military might, Russian ships in the Caspian Sea fired a barrage of cruise missiles at rebel positions in Syria, a distance of more than 1,000 kilometres.

The payback was not long in coming.

On October 13, the compound of the Russian embassy in Damascus was hit by two shells, causing little damage. But on October 31, in a far more ominous and dangerous turn of events, a Russian civilian charter airliner returning to Russia from the seaside Egyptian resort of Sharm el-Sheikh in the Sinai Peninsula broke up in mid-air and crashed, claiming the lives of 224 passengers and crew.

It was the worst disaster in Russian aviation history.

Sinai Province — an affiliate of Islamic State — claimed responsibility. Its claim is plausible. Experts believe that a bomb was placed aboard the Russian plane before it departed on its ill-fated flight.

Concerned with the safety of its citizens, Russia has since cancelled all flights to and from Sharm el-Sheikh, but the Russian government has not backed down from its commitment to help Assad regain the initiative on the battlefield. Assad has been on the defensive of late, having ceded a great deal of ground to his enemies since the outbreak of fighting in 2011.

By all accounts, three-quarters of Syrian territory is now in the hands of an ideologically diverse band of insurgents ranging from secularist nationalists to Islamic fundamentalists and Kurds.

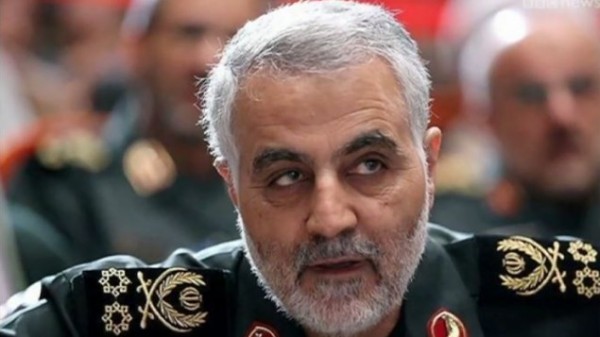

Iran supposedly played a key role in persuading Russian President Vladimir Putin to send a military contingent to Syria. General Qassem Suleimani, head of Iran’s Quds Force, went to Moscow in August with the message that direct Russian involvement was imperative to keep Assad’s besieged Alawite regime afloat. The Alawites, a Shiite sect vastly outnumbered by Sunni Muslims, have controlled Syria since the late 1960s.

Suleimani reportedly told Putin that unless Russia intervened, Assad’s Alawite base along and near the Mediterranean coast might fall, leaving Russian interests in Syria gravelly imperilled. As Russia’s oldest strategic Arab ally in the Middle East, Syria has given Moscow access to a warm-water port in Tartus, its only naval base outside Russia. Syria is also a significant importer of Russian weaponry and consumer goods.

Twenty thousand Russian advisors were kicked out of Egypt in 1972, leaving Syria as Moscow’s most reliable ally in the Arab world.

Chastened by Suleimani’s bleak report, Putin agreed to dispatch some 50 aircraft, pilots and mechanics to Latakia, which is guarded by a force of some 2,000 Russian soldiers and long-range missile batteries.

The Russian presence in Syria is Moscow’s first military engagement abroad since its intervention in Afghanistan in 1979, a mission that proved to be its “Vietnam.”

Putin’s aims are clear: to defend and prop up Assad’s government, to boost Russia’s influence in the region, to deal Islamic State blows and to deflect attention away from Russia’s meddling in Ukraine.

In the first round of attacks, Russian jets and helicopters pounded rebels aided by the United States, prompting vocal complaints from the Obama administration. Russia countered by saying it was bombing “terrorists.”

Russia’s air campaign also angered Turkey, a NATO member whose airspace was twice violated by Russian aircraft. In the face of these penetrations, sloughed off as accidents by Moscow, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan warned Russia it was endangering its robust commercial relations with Turkey.

Russia, of course, is not the sole foreign power actively supporting Assad. Iran, Assad’s longtime Shiite ally, has reportedly sent several thousand troops to Syria, as has Hezbollah, the Lebanese Shiite militia headed by Hassan Nasrallah. Two Iranian generals and about 1,000 Hezbollah fighters have been killed so far. Iraqi Shiite militias, as well as advisors from Cuba — a staunch Russian ally — have joined the fray too.

The conflict in Syria has thus become a messy proxy war, pitting Russia and its mainly Shiite allies against the United States and a coalition of Sunni Arab nations like Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Turkey.

Backed up by Russian air power, Syria and its allies recently mounted an offensive to retake captured territory. Among the objectives is the contested city of Aleppo, whose historic old quarter has been virtually destroyed. Until now, Russian strikes have killed about 600 fighters and civilians.

Some of these fighters are Muslim citizens of Russia. By Moscow’s count, upwards of 7,000 Russian Muslims are fighting with Islamic State and other extremist organizations.

The Russian offensive is apparently working, having raised the Syrian regime’s morale. “The balance of forces right now are in Assad’s advantage,” General Joseph Dunford Jr., chairman of the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, said recently.

As a result of these developments, the United States has taken a series of comparatively bold steps to upgrade its assistance to the rebels and to degrade Islamic State.

Washington, having abandoned a $500 million program to build a viable rebel force inside Syria, has provided moderate rebels with an unknown quantity of anti-tank missiles and munitions and announced plans to deploy up to 50 commandos in Kurdish-administered areas in northern Syria.

The United States has also stepped up its bombing campaign against Islamic State in northeastern Syria in the hope of exerting further pressure on Raqqa, the group’s de facto capital. American jets take off from, among other places, bases in Turkey.

Since September 2014, the United States and its allies have carried out 2,700 air strikes against Islamic State in Syria, but they have had little impact, General Martin Dempsey, the former chairman of the U.S. Joints Chiefs of Staff, has acknowledged.

With Syrian skies full of Russian and American aircraft attacking an assortment of various targets, the United States and Russia finally agreed to establish safety protocols regulating all flights over Syria and requiring all planes to keep a safe distance from each other. This technical agreement was signed following a Russian complaint that the United States was not cooperating with Russia to avoid accidental clashes.

Russia and Israel signed a similar accord in October after Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu conferred with Putin in Moscow and a Russian military delegation subsequently visited Tel Aviv for talks on military coordination. These negotiations were conducted by the Israeli chief of staff, General Gadi Eisenkot, and his Russian counterpart, General Valery Gerasimov.

Israel’s agreement with Russia was necessary because Israel occasionally bombs convoys in Syria transporting weapons to Hezbollah, Israel’s mortal enemy. On November 11, Israeli aircraft reportedly struck an Iranian weapons shipment near Damascus airport bound for Hezbollah. It was the second such strike in about two weeks, underscoring Netanyahu’s recent warning that Israel will not tolerate such shipments.