The sudden, unexpected downfall of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad last month was a searingly stunning blow to Russia’s status in Syria, its ambition to be a key player in the Middle East, and its international prestige.

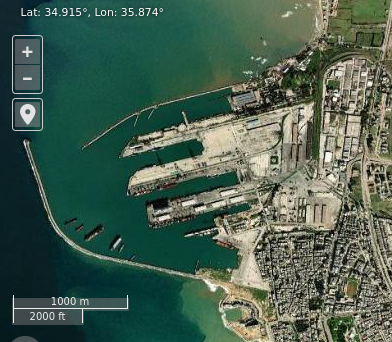

Syria was not only Russia’s chief client state in the region, but the locale of its only military bases in the Arab world, the warm-water naval facility in Tartus and the Hmeinmim air base near the city of Latakia.

With the Syrian jihadist group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) having ousted Assad’s secular regime, Russia’s foothold in Syria has been rendered tenuous.

Incredibly enough, Russian President Vladimir Putin has tried to portray the upheaval in Syria as a success for Russia. “We came to Syria 10 years ago to prevent the creation of a terrorist enclave there,” he said in a reference to Russia’s military intervention in Syria to save Assad’s regime during the fourth year of the Syrian civil war. “We have achieved that goal, by and large.”

Putin’s rosy assertion is partially correct. Russia, in tandem with Iran and Hezbollah, turned the tide of the civil war in Assad’s favor.

In the final analysis, however, Putin’s claim cannot be reconciled with reality. First, HTS may yet close the two bases that enable Russia to project influence in the Middle East and Africa. Second, Turkey, HTS’ longtime ally, has supplanted Russia as the preeminent foreign power in Syria.

That said, Putin was not far off the mark when he observed that Israel has been the “main beneficiary” of the precipitous collapse of the Assad family dynasty, which ruled the country autocratically from 1970 onwards.

Since Assad’s fall in the first week of December, Israel has destroyed a large proportion of Syria’s strategic stock of weapons so that they do not fall into the hands of Islamic State and other hostile forces. And Israel has unilaterally seized the Syrian side of Mount Hermon and the United Nations demilitarized zone adjacent to the Golan Heights.

Israel’s actions underscore the fact that Syria has never been as weak and vulnerable as it is today. The Syrian government that Israel faces today is virtually toothless and in no position to challenge Israel militarily, as its de facto leader, Ahmed al-Shara, admitted recently.

Shara’s Islamist government, which is still the process of consolidating its grip over the country, is at best lukewarm to Russia. No one has forgotten Syria’s history with the Russians. Along with Iran and Hezbollah, Russia was instrumental in propping up Assad’s police state. And from the early 1960s onward, Russia, the successor state of the now-defunct Soviet Union, was Syria’s indespensible ally and its principal arms supplier.

In other words, Russia was complicit in Assad’s crimes. Nevertheless, Russia is hopeful that it can claw its way back into Syria’s good graces.

When the Syrian uprising broke out, Russian media dismissed HTS as “terrorists.” But when Assad was in real peril of being deposed, Russian newspapers and radio and television stations abruptly toned down their language and described HTS as “militants” and the “armed opposition.”

Russia’s military response to the rebellion was anemic by its own standards. Russian aircraft struck the advancing rebels, reportedly killing more than 300 and destroying 55 vehicles, but its brief offensive on Assad’s behalf was much less intense than its previous operations in Syria.

The reason for Russia’s comparatively mild reaction can be summarized in a single word: Ukraine. Russia was preoccupied by the war in Ukraine, which it started with its invasion of its Slavic neighbor in the winter of 2022. What was supposed to be a cakewalk for Russia degenerated into a quagmire of Vietnam proportions. Russia has paid dearly in men and materiel for its aggression.

On a practical level, Russia pulled many of its aircraft out of Syria and committed them to subduing Ukraine, thereby undercutting its ability to defend Assad effectively.

The Russian garrison in Syria was also weakened when the Wagner group, the Russian mercenary force that had acquitted itself well in Syria, was dissolved in 2023 after its leader, Yevgeny Prigozhin, staged a failed mutiny in Russia.

And warships that Russia might have dispatched from the Black Sea to the Mediterranean Sea were blocked by Turkey under the 1936 Montreux convention, which governs the passage of ships through the Bosporus and Dardanelles straits.

On the eve of the rebellion, 7,400 Russian military personnel, from soldiers to sailors, were stationed in Syria. Russia sent the first of its troops there almost a decade ago to shore up Assad’s sagging fortunes. With rebels closing in on his unpopular regime, the commander of Iran’s Quds Force, Qassem Soleimani, flew to Moscow and strongly urged Putin to give Assad a helping hand.

Realizing that Russia’s political investment in Syria was in dire jeopardy, Putin agreed to send reinforcements in the form of advisors and aircraft. It was a message to friends and adversaries that Russia was prepared to stand by its allies. But it also turned out to be a costly gambit, with 543 Russians having been killed in Syria between 2015 and 2024.

During this period, Russia and Israel reached an important understanding regarding Israeli air raids in Syria. Assad, having allowed Iran and its proxies to establish a military presence in Syria from which to attack Israel, felt the consequences of his decision when Israel carried out retaliatory strikes on a regular basis. Russia, unwilling to get dragged into this conflict, turned a blind eye to Israel’s bombing campaign, which was primarily aimed at Iranian bases and Hezbollah arms convoys en route to Lebanon.

On the whole, this arrangement worked to Israel’s advantage. But at times, it fizzled, causing tension between Russia and Israel.

These unpleasant incidents, including the accidental downing of a Russian reconnaissance plane with its entire crew, were of a relatively minor nature compared to the rough-and-tumble of Israeli-Russian relations from the 1960s until the 1990s.

Although the Soviet Union was one of the first countries to recognize Israel’s declaration of independence in 1948, it adopted a resolutely pro-Arab policy from that point onward. During the Cold War, Russian influence in Syria, Iraq, Egypt and Algeria grew exponentially as Russia became their source of weapons.

The Russian footprint was especially pronounced in Syria, the so-called beating heart of Arab nationalism. On the eve of the 1967 Six Day War, the Russians issued warnings, denied by Israel, that Israeli troops were massing on the northern border with Syria. These rumors destabilized the region.

In the wake of the war, Russia resupplied the Syrian armed forces following its defeat and its loss of the Golan. Six years later, Russian advisors were on the Golan when Syria, in concert with Egypt, initiated the Yom Kippur War.

By then, Russia had severed diplomatic relations with Israel for the second time since the early 1950s.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Russia reestablished bilateral relations with Israel. But Russia’s key regional ally, the jewel in its Middle Eastern crown, remained Syria.

But now, with Assad gone and a new unfriendly order rising in Damascus, it appears that Russia has lost Syria. It is a devastating setback to Russian aspirations in the Middle East.