Much to Israel’s disappointment, Saudi Arabia in the short term is unlikely to follow the lead of the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain and sign a normalization agreement with Israel.

Saudi Arabia — the seat of Islam and the site of some of the holiest shrines in the Muslim world — is sticking to its guns, notwithstanding intense U.S. pressure to reverse its policy.

The Saudis will not establish diplomatic relations with Israel unless the thorny Palestinian question is resolved by means of a two-state solution, a formula to which Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu pays lip service but which he rejects on political and security grounds.

That said, Saudi Arabia, which has had clandestine relations with Israel for years, has been taking baby steps toward forging formal relations with the Jewish state.

Following the news that the United Arab Emirates intended to make peace with Israel, Saudi Arabia allowed an EL Al passenger plane to fly to the United Arab Emirates through its air space. And in an announcement shortly afterward, the Saudi government let it be known that Israeli aircraft would henceforth be permitted to fly over its territory.

Saudi Arabia tacitly endorsed the United Arab Emirates’ and Bahrain’s peace pacts with Israel, but it declined to send a representative to the signing ceremony at the White House in September.

Prince Mohammed bin Salman, the de facto Saudi ruler, was invited to attend the event, but he boycotted it. His presence would have publicly signalled implicit Saudi recognition of Israel. It may also have improved his battered image, which was badly tarnished by the grisly murder of Jamal Khashoggi, a dissident Saudi journalist who was killed in Istanbul two years ago on his orders, according to the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency.

The prince reportedly fears that normalization would be opposed by diehard conservatives in Saudi Arabia and would be used by rivals to undermine his position as his father’s successor to the throne.

This is probably true. For decades, Saudis have been brainwashed by the media, the clergy, the political class and the education system to believe that Israel is an aggressive and illegitimate state that has no right to exist.

Prince Mohammed is also aware that his father, King Salman, is a keen supporter of the Palestinian cause and will nor formally recognize Israel unless it reaches an agreement with the Palestinians on Palestinian statehood.

The United States, nevertheless, has been trying to nudge Saudi Arabia, one of its key Arab allies, to soften its stance toward Israel. In August, U.S. President Donald Trump said he expected Saudi Arabia to recognize Israel “at the right time.”

On September 7, King Salman poured cold water on the idea.

While expressing appreciation for the United States’ diplomatic efforts on behalf of peace, he reiterated his view that the 2002 Arab League peace initiative, which was renewed in 2007, should be the basis of an Israeli-Palestinian accord.

The proposal calls for Arab recognition of Israel in exchange for its withdrawal from the occupied territories, its acceptance of Palestinian statehood and its readiness to resolve the Palestinian refugee problem.

Israel rejected the Arab plan.

In a virtual speech to the United Nations General Assembly on September 23, King Salman voiced support for “all efforts aimed at advancing the peace process.” He did not explicitly endorse Israel’s peace accords with the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain, but rather reaffirmed his position in favor of a Palestinian state, with East Jerusalem as its capital.

Undeterred by the king’s comments, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo brought up the issue again on October 14. He said he hoped that Saudi Arabia would consider normalizing its below-the-radar relationship with Israel in the interests of countering Iran and generating regional prosperity.

In response, Saudi Foreign Minister Prince Faisal bin Farhan replied, “We have always envisioned that normalization would happen, but we also need to have a Palestinian state and we need to have a Palestinian-Israeli peace plan.”

“I believe that the focus now needs to be on getting the Palestinians and the Israelis back to the negotiating table,” he added, thereby tacitly rejecting the Trump administration’s peace proposal, which was released in January and dismissed by the Palestinian Authority as a betrayal. “In the end, the only thing that can deliver lasting peace and lasting stability is an agreement between the Palestinians and the Israelis.”

Despite the Saudis’ resistance to normalization under current conditions, Saudi Arabia has been moving in that direction incrementally, spurred on by its bitter rivalry with Iran, the preeminent Shi’a power in the Middle East.

In laying the groundwork for a possible rapprochement with Israel, the Saudi government has been trying to change public perceptions about Jews, who have long been vilified in Saudi Arabia.

Two years ago, Prince Mohammed broke with tradition by saying that the Israelis, as well as Palestinians, have a right to their own land, and that Saudi Arabia shares “a lot of interests” with Israel.

Last January, Saudi cleric Mohammed al-Issa, the head of the Muslim World League, attended a ceremony in Poland marking the 75th anniversary of the liberation of the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp.

Last month, the imam of the Grand Mosque in Mecca, Abdulrahman al-Sudais, delivered a sermon praising the Prophet Mohammed’s friendly relations with Jews. Al-Sudais’ promotion of religious tolerance was a far cry from the days when he spouted antisemitic conspiracy theories about Jews.

And in a further break with the past, Arab News, Saudi Arabia’s main English-language newspaper, recently carried a series on the Jews of Lebanon and plans to publish stories about the ancient Jewish community of Saudi Arabia.

Not too long ago, Saudi school textbooks denigrated Jews and Christians as infidels, apes and pigs, but these books are now being revised in line with Prince Mohammed’s campaign to combat extremism in schools.

Saudi Arabia’s gradual drift away from Islamic fundamentalism remains a work in progress which may or may not succeed. But in a reflection of its evolution, the Saudis have begun to openly criticize the Palestinian leadership.

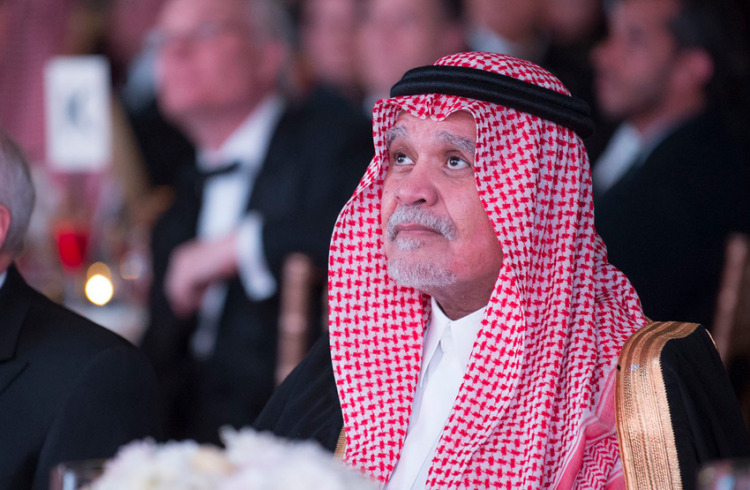

Earlier this month, Prince Bandar bin Sultan bin Abdulaziz, the former Saudi ambassador to the United States, condemned the former leader of the PLO, Yasser Arafat, and lambasted certain aspects of Palestinian policy since the first Arab-Israeli war in 1948.

As he put it, “The Palestinian cause is a just cause, but its advocates are failures and the Israeli cause is unjust, but its advocates have proven to be successful. That sums up the events of the last 70 or 75 years. There is also something that successive Palestinian leadership historically share in common. They always bet on the losing side, and that comes at a price.”

Presumably, he was also referring to the Palestinians’ rejection of the United Arab Emirates’ and Bahrain’s normalization agreements with Israel.