It seemed like a bolt out of the blue, but it was actually the end result of arduous negotiations.

A day after The New York Times published a story setting out Saudi Arabia’s conditions for making peace with Israel, Saudi Arabia reestablished diplomatic relations with its rival, Iran, after a hiatus of seven years.

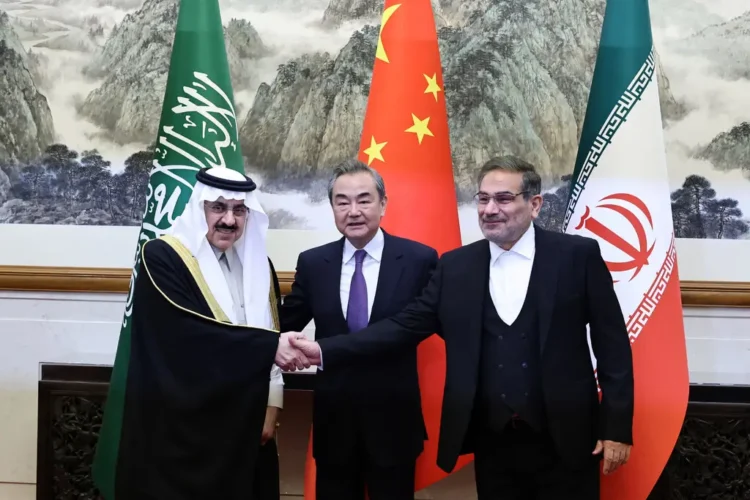

The news was announced at a ceremony in Beijing on March 10, underscoring China’s ascendancy as an influential power in the Middle East after the United States and Russia. China brokered the agreement at a moment when Israel was counting on the United States, its chief ally, to bring it together with Saudi Arabia to fend off Iranian aggression in the region.

Under the agreement, Iran promised to halt attacks on Saudi Arabia and curtail support for proxies, such as the Houthis, that have fired hundreds of missiles and armed drones at the desert kingdom.

Until 2022, Iran and Saudi Arabia fought a proxy war in Yemen, where Houthi rebels aligned with the Iranian regime battled the Saudi army. Hostilities essentially ended with a ceasefire endorsed by the United Nations and the United States.

Israel was stunned by the turn of events in Beijing, even though Saudi and Iranian diplomats had been working on this problem for almost two years.

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who has been promoting a rapprochement with Saudi Arabia as a means by which to expand the 2020 Abraham accords and build a regional security front against Iran, was surely surprised and disappointed by this development.

On the eve of China’s announcement, he talked about the possibility of building a railway line between Israel and Saudi Arabia, the seat of Islam. He made this comment during a state visit to Italy.

But with Saudi Arabia having mended fences with Iran — the preeminent Shi’a power in the region — Netanyahu’s hopes of forging a strategic alliance with the Saudis hang on a slender thread.

Realistically, the prospect of such an alliance was little more than a pipe dream, given the Saudis’ unwavering insistence that a normalization of relations with Israel is conditional on a resolution of Israel’s conflict with the Palestinians through a negotiated two-state solution.

The Saudi foreign minister, Prince Faisal bin Farhan al-Saud, reiterated this point early in January at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, when he said, “True normalization and true stability will only come through … giving the Palestinians a state.”

Judging by a report in The New York Times, Saudi Arabia’s price for making peace with Israel transcends the Palestinian cause. In exchange for establishing formal relations with Israel, the Saudis apparently demanded security guarantees from the United States, assistance to build a civilian nuclear program, and a loosening of restrictions on the sale of U.S. weapons.

In public, however, the Saudis have not deviated in the least from their position that a breakthrough with Israel can only be achieved after the advent of Palestinian statehood.

Twenty one years ago, at an Arab League summit in Beirut, Saudi Arabia offered Israel a peace treaty if it accepted a two-state solution on the basis of a complete Israeli withdrawal from the occupied territories and the creation of a Palestinian state in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. Israel basically rejected the proposal, which is still on the table, and continues to regard it with suspicion.

The Arab League proposal, backed by the Arab League, blocks Netanyahu’s path to official relations with Saudi Arabia because he and his far right-wing government staunchly oppose Palestinian statehood. At best, he is willing to grant the Palestinians a measure of autonomy under a regimen of Israeli control of the West Bank, a plan the Palestinian Authority has dismissed out of hand.

Netanyahu may believe that Saudi Arabia’s condition for peace is merely rhetorical. Under the Abraham accords, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Morocco and Sudan agreed to normalize relations with Israel without resolving the gnawing Palestinian issue. Significantly enough, Saudi Arabia did not object to these arrangements.

Nearly three years on, Saudi Arabia’s decision to renew relations with Iran sends a stark message to Israel that an Israeli alliance with Arab states to counter Iran may not be a feasible proposition today or in the near future.

It also underscores another reality.

The majority of Arab leaders, from Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman to Egyptian President Abdul Fattah el-Sisi, regard diplomacy and dialogue as the optimum way of dealing constructively with Iran.

This leaves Israel isolated as the only Middle Eastern state seriously considering the use of military force to destroy Iran’s nuclear sites, which are dispersed throughout the country in deep underground shelters.

Israel’s policy is grounded in the belief that only a credible military threat may deter Iran from weaponizing its nuclear program to full capacity. Since the United States unilaterally withdrew from the 2015 nuclear accord in 2018, Iran has reportedly succeeded in enriching uranium to 84 percent purity.

Alarmed by Iran’s capabilities or intentions, the Israeli government may yet launch massive air strikes against Iran’s nuclear facilities. But Israel would effectively be acting on its own, outside the framework of a regional alliance that might have included Saudi Arabia.

Yair Lapid, Netanyahu’s immediate predecessor and the leader of the opposition in the Knesset, denounced Netanyahu over the Saudi-Iranian agreement. In a tweet, he wrote that it represents “a total and dangerous failure of the foreign policy of the Israeli government … a collapse of the regional wall of defence that we began to build against Iran.”

Naftali Bennett, who preceded Lapid as prime minister, described it as a “serious and dangerous development for Israel” and a “political victory for Iran.” It is “a fatal blow to efforts to build a regional coalition against Iran,” he added.

Interestingly enough, Iran concurs with this assessment. Its National Security Council secretary, Ali Shamkhani, said the agreement “will definitely be a serious obstacle to the presence and interference of extra-regional countries and the Zionist regime in the region.”

Before Netanyahu’s return as prime minister late last year, Lapid disclosed he had initiated secret contacts with the Saudi government in the quest to achieve a diplomatic breakthrough in a “short period of time.” In this spirit, Lapid delivered a speech at the United Nations expressing support for a two-state solution.

Noting that agreements had been reached with the Saudis to allow Israeli civilian aircraft to overfly Saudi territory en route to Asian countries and to permit Israeli Arabs to worship in Mecca, Lapid said he had “laid the groundwork” for Saudi Arabia to join the Abraham accords.

For this to happen, however, Israel will have to sincerely embrace a two-state solution and reopen peace talks with the Palestinian Authority, which broke down in the spring of 2014.

Is Netanyahu ready or able to change his hardline policy with respect to the Palestinians? Judging by his views and the nature of his coalition, the answer is a resounding no.

Which inevitably means that Israel will fall short of its objective to normalize relations with Saudi Arabia.

Israel’s failure will be Iran’s success.