Twenty five years have elapsed since I watched Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List, his riveting and powerful 195-minute film set during the Holocaust in Poland. Having left an indelible impression on me the first time around, I was eager to see it again at a Spielberg retrospective at the Toronto International Film Festival.

In the re-release of the movie, which won seven Academy Awards, Spielberg delivers a short and timely introduction. Given the resurgence of open antisemitism of late, he speaks of the tragic consequences of bigotry and discrimination and expresses the hope that love is stronger than hatred.

It’s a fitting comment because the central character in Schindler’s List, based on a book by Thomas Keneally, is Oskar Schindler (1908-1974), the Sudeten German industrialist and Nazi Party member who, out of the goodness of his heart, rescued about 1,200 Polish Jews in the final months of Germany’s fanatical campaign to exterminate the Jews of Europe. In 1958, Yad Vashem — the Holocaust memorial-cum education centre in Jerusalem — recognized him as a righteous gentile. When he died, a hero in the eyes of Holocaust survivors, he was laid to rest in Israel.

A high-living hustler who preyed on the disasters of the brutal Nazi occupation of Poland, Schindler was an entrepreneur who revelled in hedonism. Wine, women, song and handsome profits kept him going as Germany ruthlessly plundered Poland and murdered Jews. Yet he was fiercely protective of his Jewish workers, and when push came to shove, he spent his personal fortune rescuing them from the clutches of death.

Spielberg paints a balanced picture of this flawed individual who redeemed himself by extraordinary deeds. And the charismatic Irish actor who portrays him, Liam Neeson, turns in a brilliant performance that inspires wonderment and admiration.

Schindler’s List, which will be screened once more at TIFF on January 5, is filmed in sharp and contrasting black-and-white hues. It begins as the smoke of two flickering sabbath candles melts into the belching gray smoke of a massive locomotive pulling into a train station in the southern Polish city of Krakow. Germany has invaded Poland, and in the wake of its conquest secular and religious Jews are lining up dutifully to register with the German authorities. Little do they know what awaits them.

In the next scene, which unfolds in a cozy, comfortably-appointed room, an unidentified man, a dandy, prepares himself for an evening’s outing. As he dresses, choosing his cufflinks carefully, he reaches for wads of money in a drawer and affixes a pin, emblazoned with a swastika, on his jacket lapel. He then strides confidently into a crowded cafe resounding to romantic music and filled with stern-looking German military personnel, beautiful German and Polish women and obsequious waiters.

He’s Schindler at his finest, slapping backs, befriending strangers, broadly smiling at every turn, trading stories, leaving unheard of tips and ingratiating himself to all and sundry. He’s the life of the party, a human dynamo. Although married, he has a mistress. As his wife Emilie (Caroline Goodall) knows, Schindler is a philanderer down to his fingertips.

Spielberg, in an abrupt shift, pans his cameras on a grimy street where an amused German soldier snips off the sidekicks of a passive Orthodox Jew in traditional clothing. The juxtaposition between the bubbly mood of the nightclub and the inhumane treatment meted out to this unfortunate Jew is jarring, to say the least.

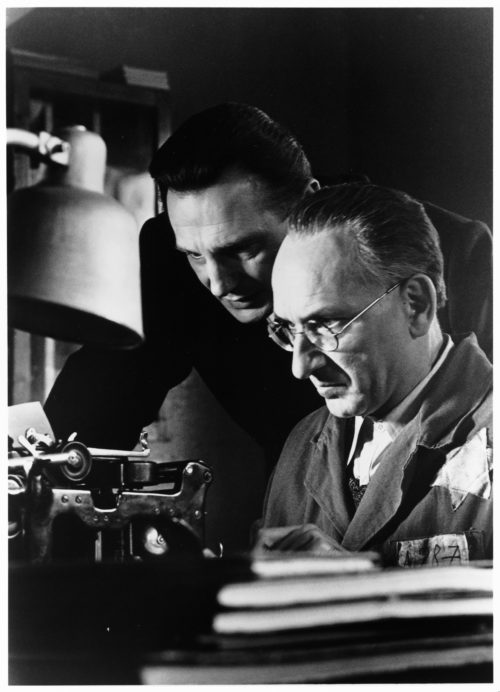

In short order, Schindler finds Yitzhak Stern (Ben Kingsley), a glum and clever accountant, at the local Judenrat, the Nazi-established Jewish council charged with maintaining law and order in the besieged Jewish community. An opportunist of the first rank, Schindler seeks lucrative war contracts and investments to enrich himself. He wants to take over a factory and manufacture enamelware for the German army, but his scheme can only work if Jewish investors put up the money and Stern agrees to manage the enterprise using cheaper Jewish laborers. Exploiting his advantage as a well-connected German in a cowed occupied city, Schindler prevails and production soon gets under way.

These are compelling scenes, captured graphically on the screen by Janusz Kaminski, a cinematographer whose eye for granular details is impressive.

Spielberg plunges headlong into the Nazi reign of terror in Krakow as he depicts Jews being driven into the congested ghetto. They’re shocked by the appalling conditions, but are virtually powerless to escape. Polish and Israeli actors portray these poor souls. Two of the Israelis enunciate their lines in thick and unmistakable Sabra accents, undermining the authenticity of their milieu.

As Jews are led away unceremoniously, a Polish girl obviously hostile to her Jewish neighbors shouts, “Goodbye Jews!”

Although Schindler’s factory produces valuable goods for Germany’s war effort, the Nazis continue to deport Jews, including his valued Jewish workers, to extermination camps. At the last possible moment, Schindler desperately rescues Stern, who’s been placed aboard a train en route to a concentration camp.

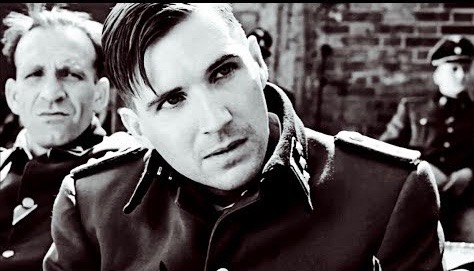

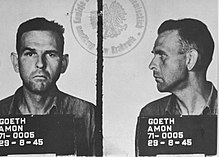

At this juncture, SS officer Amon Goth (Ralph Fiennes) is introduced. Ordered to build the Plaszow camp, near Krakow, Goth is evil and cruel, a genuine villain. When a Jewish woman, a trained engineer, earnestly informs him the foundations of a building are faulty and must be rebuilt, he exhibits rage rather than gratitude and has her immediately shot.

As the ghetto is violently emptied of its bedraggled inhabitants, Schindler and his girlfriend watch the horrific proceedings on horseback from a hill. The pain on his face is palpable. He doesn’t utter a word as hapless Jews are roughly rounded up. Some are shot as they try to flee the carnage and find hiding places. In a signature scene of uncommon power, a little girl in a distinct red jacket ducks into an abandoned building, hoping to elude the Nazis.

Goth revels in the misery he’s creating. Standing half-naked on his balcony in Plaszow, he casually shoots Jews in faux target practices. His distressed Polish girlfriend, clad in a negligee, asks him to stop.

As the atrocities pile up, Schindler complains. “Every worker shot costs me money,” he lectures Goth. “It’s bad for business.”

Having established a sub-camp to house his workers, Schindler must pay off Goth and an assortment of venal and corrupt Germans. “Independence costs money,” Goth sneers in a mincing voice, conveying his mercenary message. Fiennes, tense and coiled, is superb as the amoral Goth.

Schindler’s gradual transformation from calculated war profiteer to warm-hearted humanitarian is on display in a pivotal scene when he helps a frantic Jewish woman trying to save her parents. From that point onward, Schindler’s loyalties change perceptively. As a train crammed with Jewish deportees leaves the station on a hot summer day, he hoses the cattle cars with cold water to provide them with a measure of fleeting relief.

“You’re giving them hope,” Goth says ironically. “That’s cruel,” he adds mockingly in a crude understatement.

With Plaszow scheduled to be closed after its inmates are deported, Schindler scrambles to relocate his factory elsewhere. Stern draws up a list of 1,200 Jewish workers who can accompany Schindler to Czechoslovakia. Goth, having been amply bribed, turns a blind eye to Schindler’s plan. It goes off smoothly, but due to a minor mistake in paperwork, one convoy accidently ends up in Auschwitz, prompting Schindler to hustle to rescue his Jews.

The film comes to a solemn close as a procession of grateful real-life “Schindler Jews” and their descendants file past his grave in Jerusalem and place mourning stones on them. It’s a poignant moment for reflection. This is a man whose self-serving habits gave way to selflessness during an incredibly dark period.

Beyond any doubt, Schindler’s List is one of the finest feature films ever made about the Holocaust. Along with Roman Polanski’s The Pianist, it plumbs the depths of Nazi madness and Jewish suffering, delivering one of the masterpieces of 2oth century cinema.