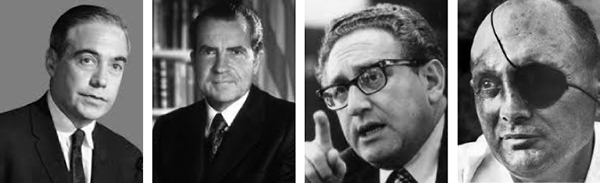

A little more than a month before his inauguration as president of the United States in January 1969, Richard Nixon dispatched William Scranton, the former Republican governor of Pennsylvania, to the Middle East on a fact-finding tour of five Arab nations and Israel. His mandate was to assess the current state of the Arab-Israeli conflict and report back to the president-elect, who had an abiding interest in this perennially unstable region.

Scranton, an amiable and self-effacing patrician who had a talent for quiet diplomacy, set off in December 1968. He seemed to be the right person for the mission. He would not ruffle feathers. He would be the quintessential diplomat.

But after crossing from Jordan into the West Bank, occupied by Israel since the Six Day War in 1967, Scranton, who died recently at the age of 96, touched off a political firestorm that went to the heart of the United States’ relationship with Israel, one of its chief allies in the Middle East.

Stopping in the town of Jericho for a press conference, Scranton said, “It is important that U.S. policy become more even-handed.” He added that the United States should deal “with all countries in the area and not necessarily espouse one.”

By “one,” he meant Israel.

Scranton’s observation was not especially original. During the 1950s, the United States struck a balance between its friendship with Israel and its interests in the Arab world. And in a significant comment on the eve of the Six Day War, President Lyndon Johnson declared that Washington would not take sides. As he put it, “Our position is neutral in thought, word and deed.”

With perhaps Johnson’s formula in mind, Scranton noted that while the United States was very attentive to Israel and its security, Washington should be mindful of its wider interests in the Middle East.

During his meetings in Israel with Prime Minister Levi Eshkol, Foreign Minister Abba Eban and Defence Minister Moshe Dayan, this potentially explosive issue apparently remained on the backburner. But after Scranton announced that the incoming Nixon administration intended to present a new Mideast “peace plan,” Israel grew concerned.

The Israeli government, fearing that Nixon would exert pressure on Israel to relinquish the occupied areas, protested. Within hours, Nixon’s press secretary, Ronald Zeigler, distanced Nixon from the “peace plan” and the concept of an “even-handed” American policy.

Being a man of conviction, Scranton reiterated his belief that U.S. policy should be “even-handed.”

Henry Kissinger, then Nixon’s national security advisor, followed these events closely. In his memoir, White House Years, he writes that “shock waves of alarm” on the part of Israel`s supporters in the United States greeted Scranton’s recommendation.

He adds, “We had a chance to calm the situation when Nixon and I met … with Israeli Defence Minister Moshe Dayan. Sharing Nixon`s wish not to start off the new administration with a U.S.-Israeli brawl, Dayan publicly denied news reports that Israel was displeased with the Scranton visit. His government felt, Dayan explained ambiguously to the press, that Scranton left Israel with à better appreciation of the issues.”

Kissinger concluded, “The Scranton flap was put behind us, but the hard rock of the Middle East impasse remained.”

Indeed.

In the wake of his visit, Scranton said, “I now believe more in the possibility of finding a peaceful solution to the Middle East conflict than when I came to this region.”

Famous last words.

Shortly after issuing these sanguine comments, Israeli commandos landed in Beirut airport, destroying 13 aircraft on the tarmac, in response to a Palestinian attack the day before on an El Al airliner.

By the following year, Israeli and Egyptian forces were engaged in an increasingly violent war of attrition in the Israeli-occupied Sinai Peninsula. In 1973, Egypt and Syria attacked Israel, triggering the three-week Yom Kippur War. In the waning days of that war, the United States, in a pro-Israel tilt that enraged Arabs from Morocco to Iraq, airlifted military equipment and munitions to Israel. In June 1974, Nixon, already embroiled in the Watergate scandal, became the first sitting U.S. president to visit Israel.

In 1976, Nixon’s successor, Gerald Ford, appointed Scranton to the post of American ambassador to the United Nations. He maintained a low profile, unlike his predecessor, Daniel Moynihan.

Forty five years after Scranton`s ill-fated trip to the Middle East, Washington’s Mideast policy is still a subject of debate in some American circles.

In 2010, Gen. David Petraeus, the then commander of U.S. forces in the Middle East, said, “The enduring hostilities between Israel and some of its (Arab) neighbors present distinct challenges to out ability to advance our interests” in the Mideast. “The conflict foments anti-American sentiment, due to the perception of U.S. favortism for Israel.”

This past May, Petraeus’ successor, Gen. James Mattis, sounded an identical theme.”I paid a military-security price every day as the commander of CENTCOM (the United States Central Command) because the Americans were seen as biased in support of Israel.”

Since recognizing the new-born state of Israel in 1948, the United States has invariably been supportive of the Jewish state. But there have always been voices who have called for a more balanced and nuanced policy.

William Scranton was one of those voices.